AN HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

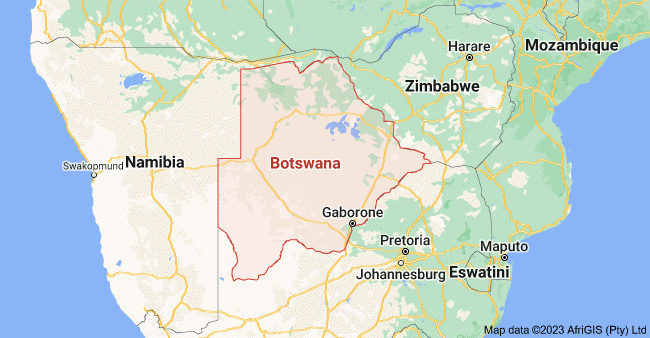

The Republic of Botswana is situated on the southern slope of the great southern African plateau. Landlocked, about 220,000 square miles (569,000 square kilometers) in area, Botswana is bordered by South Africa to the south, Namibia to the west and to the northwest (along the Caprivi Strip}, Zimbabwe to the east, and Zambia to the north.

Except for the plateau area, which is 4,320 feet above sea level (1,350 meters}, running parallel to the southeastern border, Botswana is mostly desert or semi-desert. Eighty percent of the nation’s people live in this eastern sector where the land is most fertile and the rain most plentiful (about 18 inches a year). Here the people raise cattle and grow subsistence crops like millet, maize (white corn}, sorghum, groundnuts, and cotton.

About one quarter of the country sustains scattered grazing for goats and cattle, but even this is restricted by swampland from the Okavango River and the Makgadikgadi Pan and by infestation by the deadly tsetse fly. Nearly half of the country consists of the Kalahari Desert.

The lowest point is in the southwest near the junction of the Shaske and Limpopo Rivers, and is 1,684 feet (513) meters) above sea level. The Okavango River is the major river system in the country. It flows southeastwards from the Angolan highlands and across the Caprivi Strip into northwest Botswana, where it drains into a depression in the plateau to form the Okavango swamps and Lake Ngami.

Although there is a seasonal flow of water from the swamps eastward into the Botletle River, most of the water is lost through evaporation and ground drainage. Collection and storage of water are the most serious and chronic problems that the country faces.

Gaborone is the capital, Serowe is the largest city, and Francistown is the industrial and commercial center. The major towns and cities are along the railroad line that runs from Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, into Botswana and southward along the eastern border into Mafeking (Mmabatho}, South Africa, where it branches off to Johannesburg and to Cape Town.

THE PEOPLE AND THEIR HISTORY

The 1981 census reported a population of 936,000, settled mostly in the east. English is the nation’s official language and Setswana is the national language. Ninety-eight percent of the people are Tswana, members of the western branch of Sotho-speaking Bantu people; two percent are San-speaking Sarwa (Bushmen).

Within the Tswana-speaking group are eight major subgroups. These are the Bamangwato (Ba- is the prefix indicating people}, the largest and most powerful group, which accounts for 35 percent of the total African population; the Bakwena; the Bangwaketse; the Bakgatla; the Bamalete; the Batlokwa; the Barolong; and the Batawana. Although cultural and linguistic differences exist among these various groups, the Batswana are basically a homogenous people.

San speakers are the original inhabitants of the southern African region and the ancestral peoples of much of Africa south of the Sahara. They are an especially hardy people, able to live from the meager offerings of the desert and thornveld. They number about 30,000 and some of them continue to lead nomadic lives. They belong to the Auen, Naron, Kung, and Heikum language groups.

Except in southern Africa, the San were absorbed through intermarriage with the Bantu as the Bantu moved southward from West and Central Africa nearly two thousand years ago. By about 1200 A.D., Iron Age Bantu farmers and cattle herders moved out from Zimbabwe into what are now called the Transvaal, northern Botswana, Swaziland, and Natal. Between 1200 and 1450, the Bantus had settled in most of South Africa.

The first Tswana-speaking peoples, the Bakwena, arrived in Botswana from South Africa in the early 1700s. The Bakwena subsequently split off into smaller groups, the Bamangwato and Bangwaketse and, later, the Batawana. By the late 1800s these four groups dominated the country.

Meanwhile in South Africa, white Afrikaner farmers (Boers) were moving northeast from the Cape in order to get away from British rule. The Afrikaners forced the Africans in the Natal and Cape areas northeastward, pushing them back upon themselves at a time when three main African chiefdoms were vying for power.

Cut off from expanding southward, many Africans moved northward to escape the tumultuous rule of Shaka and the Zulus. Many of these people fled to what are now eastern Botswana and western Zimbabwe.

Unlike the Ndebele, an offshoot of the Zulus who continued a militarily-oriented society in what is now southwestern Zimbabwe, the Tswana never developed a military. They were defenseless when the Afrikaners later sought their land along the Limpopo River. In the Transvaal the Afrikaners took land away from the Africans and in doing so pushed the Tswanaspeaking Bakgatla into what is now Botswana in 1871.

Not content to leave the Tswana in peace, both British and Afrikaner had their eyes on their territories. During the early 1800s Europeans had alienated land around Lobatse, Gaborone and Tuli in the southeast, Gazi in the west, and along the Molop River in the south. The 1869 Tati Concession near Francistown gave private mining companies the right to exploit an area of more than 2, 000 square miles (3,333 square kilometers).

The territory’s location was also important to both the British and the Afrikaners. The Afrikaners were settled in the mountainous Transvaal in northwest South Africa; in the west, along the Atlantic Ocean, the Germans occupied South West Africa (now Namibia). and what is now Botswana was all that stood between the two areas. As the territory gave the British access from South Africa northward to the rest of the continent, they wanted to keep it out of GermanAfrikaner hands. Cecil Rhodes called it the “Suez Canal to the North.”

In the early 1880s when several Tswana chiefs asked the British government for protection against encroaching Afrikaner farmers, Britain agreed, and in 1885 transformed the territory into the Bechuanaland Protectorate. In exchange for protection, the Tswana chiefs had to relinquish some of their land for the construction of a British-built railroad and for European settlement. Ten years later the British government again interceded on behalf of the chiefs who feared a takeover by the British South Africa Company, which was dominated by Cecil Rhodes.

The Bechuanaland Protectorate was administered by a resident commissioner under the direction of a British High Commissioner in South Africa; local affairs were directed by African authorities and councils. When South African provinces formed a union in 1910, Britain, reflecting the thinking at that time, provided for Bechuana-land’s eventual incorporation into the Union of South Africa.

A hillside Batswana settlement.

TOWARD INDEPENDENCE

From the 1920s until 1950, racially segregated advisory councils represented the people of the territory. In 1950 a joint advisory council was established; it included eight Africans and eight Europeans, all of whom were selected by their respective councils, and four appointed senior officials. In 1958 a legislative council was instituted and in 1961 a new constitution gave the legislative council limited powers.

Also in 1961, South Africa, under the control of the Afrikaner’s Nationalist party, left the Commonwealth of Nations and became a republic. The Nationalist government requested that Bechuanaland be incorporated into South Africa, but the British refused the request. Instead, Bechuanaland was given colonial status, and was set on the road to independence as the state of Botswana.

South African events, however, continued to influence developments in the territory. In the early 1960s the South African government outlawed the African National Council (ANC) and other African nationalist groups opposed to the Nationalist government and its system of apartheid. In consequence, many political activists sought refuge in Bechuanaland.

They brought with them differing political views and their influence resulted in a split in the Botswana People’s Party (BPP) the existing political party. The BPP fragmented into several new parties: what is now the Botswana People’s Party, with ties to the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC); and the Botswana Independence Party, with ties to the multiracial ANC. In 1962 Seretse Khama, chief of the Bamangwato people, broke from the BPP and formed the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP).

In 1965 internal self-government was realized, and the country held its first direct general elections. Seretse Khama’s BDP won 28 of the 31 legislative seats. In the same year, Britain granted Botswana independence, and Khama became the country’s first president.

POLITICS TODAY

Shortly after independence, Botswana was faced with turmoil on its eastern border with what was then the British colony of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). In 1965 the prime minister of Southern Rhodesia, Ian Smith, broke with Britain and declared Rhodesia independent. Although the Botswana government abhorred the political developments in Rhodesia it could not afford to close its borders leading to the territory. Rhodesia owned the railroad that connected Botswana with South Africa, its outlet to the sea. Botswana was therefore obliged to assume a neutral position, denying nationalist Zimbabwe guerrillas use of military bases in Botswana, but allowing them to pass through or to seek sanctuary there.

In 1977 intensive fighting in what is now Zimbabwe finally obliged Botswana to establish a permanent Defence Force (BDF) to patrol its borders. Rhodesian army forces had increased their incursions into Botswana in pursuit of guerrillas and more and more refugees from Rhodesia were asking for asylum.

In 1980, when Zimbabwe gained its independence, relief came to Botswana when most of the 25,000 refugees returned home and the army incursions ended. Seretse Khama, however, did not live long enough to enjoy this period of respite for he died the same year. After a secret ballot was held, his long-time associate, Quett Masire of the Bangwaketse, was elected by the National Assembly to succeed him.

In a democratic, multi-party election, held in 1984, the people of Botswana elected Quett Masire’s Botswana Democratic Party to retain power.

Generally, Botswana has maintained the same policies as those it followed under Khama’s leadership, especially that of non-alignment with its neighbors. Although Masire’s relations with Zimbabwe Prime Minister Robert Mugabe were cool, in 1983 Zimbabwe and Botswana established diplomatic relations. Botswana meanwhile retained firm economic ties with South Africa but did not have diplomatic relations with it.

ECONOMIC RESOURCES

On the surface Botswana is mostly desert or semi-desert, which is suitable for ranching. The country’s exports are mostly cattle and other animal products, and cotton. Ninety percent of its imports come from South Africa and include consumer goods, vehicles, maize (white corn) and other foodstuffs, and petroleum.

Below the surface, however, Botswana is blessed with enormous mineral resources, especially diamonds, but also coal, copper-nickel, manganese, gypsum, soda ash and potash. The Orapa and Jwaneng diamond mines are among the world’s largest producers with a 30-year potential for commercial exploitation. The mines are owned jointly by the Botswana government and DeBeers of South Africa. In 1967 -68 mining contributed 1.6 percent to the GDP; now, however, mining is the largest contributor.

The southern African region suffered from severe drought in the 1980s. In consequence, the people of Botswana were able to produce only about five percent of their food needs during this period. Many people came to the towns in search of food and employment.

Good lands and accessibility to cattle grazing lands are unevenly distributed among the people. There are three times as many head of cattle as there are people and nearly half of the total herd is owned by five percent of the people. Many men who cannot earn a living from agricultural work seek employment in South African mines. Although by the early 1990s, the number of Botswana workers in South Africa had decreased from 55,000 to about 20,000, workers continued to bring in much needed foreign exchange.

As the location for the headquarters for the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC), Botswana has been incorporated into the mainstream of African affairs.