HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

By:

Dr. Eugenio Nkogo Ondo

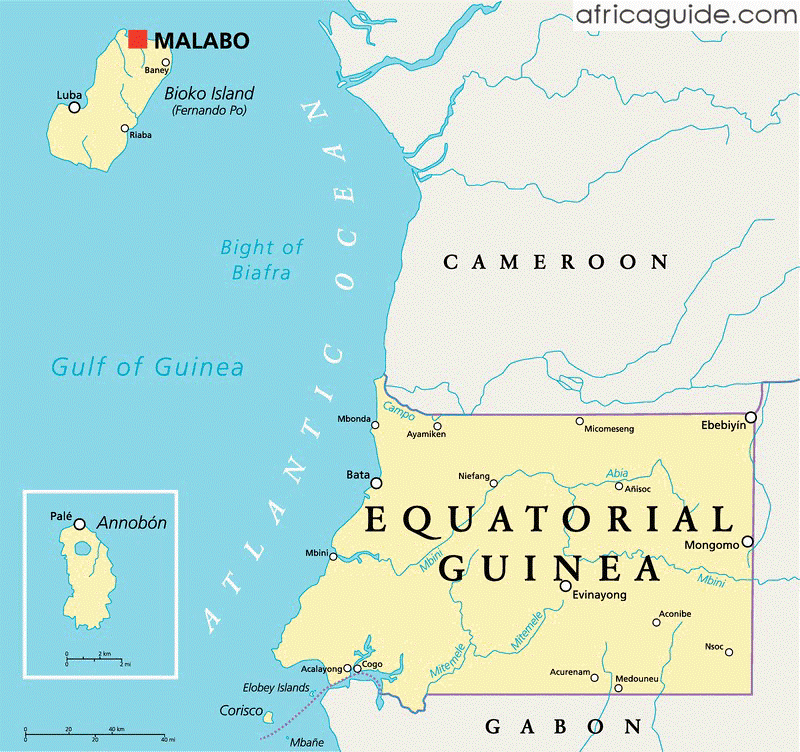

Equatorial Guinea is the modern name given to the former Spanish colony known as the Equatorial Region of Spain. It consists of Continental Rio Muni and the Island of Fernando Po, Great and Little Elobeys, Corisco and Annobon. It is a small country, only 28,051 square kilometres with a population of 400,000.

Fernando Po is a volcanic island shaped like an irregular parallelogram and lies north-east to south-west, about 35 kilometres from Cameroon. It is a mountainous country; Santa Isabel has the highest peak about 3,000 metres above sea level. The inhabitants call it the ‘’pearl of the Atlantic’’ because of its natural beauty.

The Island of Annobon forms parT of the Province of Fernando Po. With an area of 17 square kilometres, it lies just south of the Equator and some 483 kilometres from Fernando Po. Rio Muni is on the mainland of the African continent and is bordered on the north by Cameroon, on the east and south by Gabon, and on the west by the Atlantic Ocean. It is 26,000 square kilometres. There are also the coastal islets of Great and Little Elobeys (2.5 square kilometres) and Corisco (15 square kilometres).

The Inhabitants of Equatorial Guinea:

Equatorial Guinea is populated by three principal ethnic groups: the Fangs, the Ndowes and the Bubis. There are also the Annobones and the Creoles.

Fangs:

The Fangs belong to the larger group called the Panhouin, a Bantu-speaking people occupying the area between the Ogoue River in Gabon and the River Sanaga in Cameroon. It includes the Ntumus, Okas, Betis, Bulu and the Fangs. Now the Fang live in the hinterland of Rio Muni some 40 to 50 kilometres from the coast and form the main ethnic group in that province.

Various theories have been formulated about the origin of the Panhouin. They seek variously to trace their ancestry to the Inhabitants of Upper Ubangui in Zaire, the Sudan and Upper Egypt. Whatever their origin by the 19th c. they were living in the Cameroon on the right bank of River Sanaga and their emigration from this area was observed by European explorers. They were forced to move out by foreign invaders, perhaps the forces of Osuman Dan Fodio.

They crossed the Sanaga in various groups. The first batches of the Panhouin were the ancestors of the Fang and the Bulu. They escaped into the forest belt under pressure from a group of their own people, the Betis, who were left to settle on the right of the Sanaga.

From that time, the migration divided into three groups. Some of the Fang went south following River Dja in Cameroon and later River Ivindo into Gabon. A second group which was predominantly Bulus moved westwards going parallel to R Nyong in Cameroon.

The Bulus were cut off by the Germans as they neared the coast, and engaged in their last wars against the Banes between 1885 and 1895. The third group made up of Ntumus and Fang penetrated the northern part of Gabon. The Fang finally settled in their present home in Equatorial Guinea. They are known by the onomatopoeic name “pamue”.

Ndowes:

They inhabit the coastal area of Rio Muni especially the mouths of Rivers Muni, Campo and Benito and the Islets of Corisco and Great Elobey. They also live in the coastal areas of Cameroon and Gabon. The Ndowes include, the Bomudis, Mogendas, Monas, Buicos, Bengas, Bapucos, Bujedas, Balengues, Basekas and Ewincos.

Their ancestors are thought to have had their original home in the interior of Rio Muni in the Savannah zone. There they were constantly harassed by some warlike people and to escape from the incessant wars, they emigrated southeastwards under the king of the Combes, Bosendye.

The first to begin the trek were the Pongoes or Pongues, followed by the Benga and Bapuco, and lastly the Combe. After crossing Rivers Campo and Bennito they arrived at the coast where most of them settled. A small number crossed the mouth of the Muni River in their dug-out canoes and finally reached the islets of Corisco, the Elobeys and others.

The Bubis:

The Bubis live on the island of Fernando Po. Their origins have not been established with certainty. Some sources claim that linguistically they belong to the Bantu and even consider their language as the most ancient of the languages of this great family.

Other sources however state that culturally the Bubis are not related to the Bantu, but are a primitive group which have occupied Fernando Po since time immemorial.

The Creoles and Annobones:

Mention must also be made of the Creoles who are the descendants of inter-marriage between Bubis and other African ethnic groups which have migrated to the island. Annobones is the term used to describe persons born in the island of Annobon.

Towards Spanish Colonization:

Nothing definite is known about the social and political organisations of the ethnic groups of Equatorial Guinea before the coming of the Portuguese. No doubt their traditional life can be assumed to have been on the same pattern as that of the better-known states like the kingdoms of the the Kongo and Monomotapa, but perhaps without the superior political systems of the latter.

Equatorial Guinea like the rest of West Africa had its first contacts with the Portuguese in the 15th c. About 1471 Fernando Po arrived on the island which was named after him.

As the slave trade grew the Portuguese concentrated their activities on the island of Sao Tome which became the entrepot for the slave trade between Guinea and the Congo and the New World. Fernando Po also had its part in this commerce. In addition the Portuguese cultivated cocoa on the island and it was from Fernando Po that the crop was first introduced into the Gold Coast (now Ghana).

In 1778 by the Treaty of San Ildefonso, Portugal ceded to Spain the islands of Fernando and Annobon in exchange for territorial concessions in South America. These acquisitions enabled Spain to have direct access to a source of slaves which she required for her plantations in America.

From 1783 onwards Spain sent a number of expeditions to explore the island, and converted Fernando Po into a big market for slave trafficking. About this time the inter-national campaign against the slave trade led by Britain had gained so much support from other European countries that Spain was forced to allow the British Navy to lease bases on Fernando Po from 1827 to 1843.

The Spanish explorations continued not only on the islands but also on the mainland in Rio Muni. In 1843, Juan Jose de Lerena Barry led one of these expeditions to the islands and King Bokoro of Corisco island and other chiefs acknowledged Spain’s sovereignty.

In 1858 Captain Carlos Chacon arrived in Fernando Po to assume office as the first Governor of the Spanish territories. He was succeeded by Juan Pellon y Rodriguez in 1865 who firmly established the Spanish presence in the territories. In 1874 Manuel Iradier toured the Muni region and founded the city of Puerto I radier (Kogo). His expeditions are regarded as very important because of the contacts he made with the indigenous people.

The French were at this time also very active in the Rio Mani region, and a competition developed between the explorers of Spain and those of France. To end the rivalry the two countries signed the Treaty of Paris (or the Franco-Spanish Convention) of 27th June, 1900 which defined the respective areas of activity of the two nations in this part of Africa. It limited Spanish activity to what at present constitutes the borders between Gabon and Equatorial Guinea in the south and between Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea in the north.

In the course of their penetration into the territories, the Spanish had much opposition from the Guineans. An expedition under Count Argelejo in 1778 was resisted by the indigenous people at the famous battle of Annobon. Towards the end of the 19th c. the Bubis offered strong resistance to the attempts by the Spanish colonisers to conscript African labour for their cocoa plantations.

After the Treaty of Paris, the Spanish attacked a big army of the Fang which for 26 years held out against the colonisers in the Muni region. The hero of this resistance was Ntutumu Maye. But the Spanish with their superior weapons were able to maintain their hold on the colony.

The Spanish treated the territory as an appendage of Spain for administrative and commercial purposes. Legislation was effected by decree from Spain. There were two classes of Africans: those fully assimilated (emancipados) who had the same status as Europeans and were subject to the Metropolitan Penal Code; the second class consisted of those who had the benefit only of limited emancipation (emancipation limitada) and generally came under Native Tribunals.

Cocoa production on Fernando Po followed the same pattern as in the Portuguese territory of Sao Thome. Arable land was concentrated in the hands of the Spanish who used imported African foreign workers to cultivate cocoa on their plantations.

Real development of the colony began after World War II. Spain encouraged the cultivation of cocoa and coffee in both provinces of the colony by subsidising their export prices. She established schools for the Africans, built roads into the interior of Rio Muni and generally opened up new areas for exploitation by Spanish commercial firms.

Equatorial Region of Spain:

On July 30th, 1959, the laws on the “Organisation of Judicial System of the Provinces of Fernando Po and Rio Muni” were promulgated in Spain. From this date the colony became an integral part of the mother country as the Equatorial Region of Spain. All Africans became technically full citizens of Spain with the same civil rights as the Spanish. As such they returned six representatives to the Cortes in Madrid. The first elections ever held in Spanish Africa took place in 1960.

But because of political and constitutional developments elsewhere in Africa the Guineans were not satisfied with this arrangement and started agitating for complete independence. The Spanish authorities reacted by adopting harsh repressive measures. It was during this struggle that Acacio Mane and Enrique Nvo were killed. The situation became very critical; the authorities arrested all those whom they regarded as “agitators”. The neighboring Republics of Cameroon and Gabon were filled with refugees from Guinea.

With the support of the governments of these two countries, the Guinean nationalists raised the matter in the General Assembly of the United Nations where many nations were in favor of decolonisation of the territory. Under this pressure the Spanish Government agreed on August 10, 1963 to grant autonomy to the territory.

Autonomy for Equatorial Guinea:

The legislation granting autonomy to Equatorial Guinea was passed in the Spanish Cortes in November 1963 and put to a referendum in the colony in December. The majority of Guineans approved the legislation.

Under the constitution there was to be a joint legislative body, the General Assembly, for the two provinces and a Council of Government which was made up of eight councilors and a President appointed by the General Assembly. The most important post was the Spanish High Commissioner because politically he held more power than both the General Assembly and the Council of Government. The Constitution came into force in January, 1964.

Three political parties contested the elections. The National Movement for the Liberation of Equatorial Guinea (MONALIGE) the Popular idea of Equatorial Guinea (IPGE) and the Movement for National Unity of Equatorial Guinea (MUNGE) Boniface Ondo Edu, leader of MUNGE was elected president.

But the Constitution did not satisfy the political aspirations of Guineans. For it soon became obvious that the Spanish Government was still firmly in control of Equatorial Guinea. The political leaders therefore continued their agitation for independence.

The Republic of Equatorial Guinea:

The movement toward independence began to take shape at the end of 1967. Early the following year the Spanish government suspended autonomous political control and, with the subsequent approval of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), proposed that a national referendum be held to approve a new constitution. The constitution was overwhelmingly approved on August 11 and was followed by parliamentary elections in September and by the proclamation of independence on October 12, 1968.

The first president was Francisco Macías Nguema (also known as Macías Nguema Biyogo Masie). After his election in 1971, he assumed wide powers and pushed through a constitution that named him president for life in July 1972. He assumed absolute personal powers in 1973, and the island of Fernando Po was renamed Macias Nguema Biyogo Island in his honour. He controlled the radio and press, and foreign travel was stopped.

In 1975–77 there were many arrests and summary executions, which brought protests from world leaders and the human rights organization Amnesty International.

Macías was overthrown in 1979 by his nephew, Lieut. Col. Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, and executed. Obiang led a Supreme Military Council, to which he added some civilians in 1981. A less authoritarian constitution was instituted in 1982, followed by the election of 41 unopposed candidates to the legislature in 1983.

Although a 1991 constitution provided for a multiparty state—leading to the first multiparty elections, held in 1993—there was no indication that Obiang would willingly give up power, and his regime was the subject of much international criticism for its oppressive nature.

In the 1990s and early 2000s the president and the members of his party repeatedly won reelection by lopsided margins in ballots that were fraught with charges of fraud. Furthermore, accusations abounded that a clique surrounding the president had systematically pocketed the bulk of the country’s considerable oil revenue, which had grown dramatically since the late 20th century.

In November 2011 Equatorial Guinea approved many changes to its constitution via referendum with a reported 97.7 percent of the vote. Changes included making the unicameral legislature bicameral, imposing a limit of two consecutive presidential terms, lifting the age limit for presidential candidates, and creating the position of a vice president, who would be appointed by the president and who would be next in line to assume the presidency should the incumbent president die or retire.

Equatorial Guinea’s 2016 presidential election was held on April 24. As in previous polls, Obiang was reelected by a huge margin—93.7 percent.

Obiang attempted to hold another national dialogue in 2018, but it was dismissed as a public relations stunt by Moto, who remained a leading opposition figure, and the event was boycotted.

The country did win accolades for a measure that abolished the death penalty, which Obiang signed into law in September 2022.