A HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

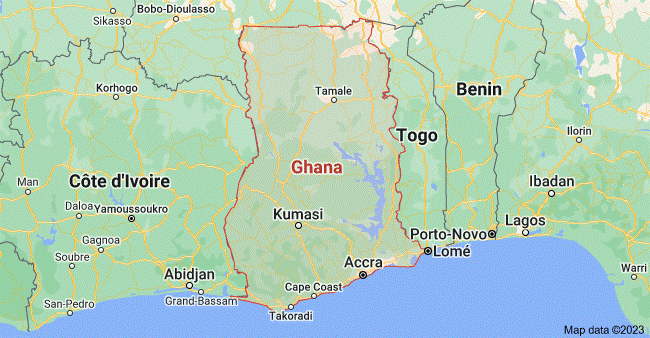

Ghana is the name which was assumed at independence on March 6, 1957, by the former British Crown Colony of the Gold Coast. Until 1957, the Gold Coast consisted of the Gold Coast Colony in the south, Asante (Ashanti), the Northern Territories, and, to the east, the Trans-Volta Togoland Region (now the Volta Region).

The suggestion that the name ‘Ghana’ be given to the Gold Coast after independence was made by Dr. J. B. Danquah (q.v.), 1895-1965, the scholar and politician. He maintained that the Akan of the Gold Coast, of whom he was one, were descendants of the inhabitants of the mediaeval empire of Ghana, which flourished from the 9th to the 13th centuries.

However, since the Ghana Empire was situated beyond Timbuktu, between the Sahara and the headwaters of the Senegal and Niger rivers, the evidence for the claim is doubtful.

EARLY ORIGINS

The inhabitants of present-day Ghana are black men, whose origins are obscure. It is assumed, however, that some of the original. ancestors of the Ghanaians came into the country from the north, while others came in later from the east, from what is now Nigeria.

The Colony, or southern Ghana, and Asante are peopled mainly by a cultural and linguistic group called the Akan, to which some of Ghana’s principal peoples belong. Until the territory became a British colony, the Akan formed several nations, extending from what is now the Ivory Coast to the west, eastward through Asante and across the Volta River to the borders of what was later to become Togo.

The two main languages of the Akan group are Twi and Fante, which have several dialects. Twi is the most widely spoken language of the country. The Ga and Adangme (Adangbe) languages, which belong to a group unrelated to the Akan, are spoken on the Accra plains, while eastwards, across the Volta and towards Togo, Ewe, another non-Akan tongue, is the principal language.

Another separate linguistic group consists of the Guan, a people who, although conquered by the Akan, nevertheless retained their own languages. In northern and upper Ghana, Dagbani, spoken by the Dagomba (Dagbon); and More, spoken by the Mossi (Moshi), both belonging to the Voltaic (Gur) language group, are the principal languages, although several other dialects are also spoken in these regions.

It is assumed that the ancestors of the Akan came southward from Gonja (Ngbanya) – a state located in what is now the lower third of the Northern Region of Ghana in about AD 1200. It is also assumed that they came in three waves.

The Guan were the first to move southward, followed by the Fante, and then by the Twi. Tradition holds that the Adanse, or ‘house builders’ formed the earliest and southernmost Twi-speaking states. Next came two more Twi-speaking peoples, the Denkyera (Denkyira), and, further north, the Asante.

In the south, the Akwamu, also Twi speaking, are the Akan nation with the longest history. The original home of the Asante was Amanse, around Lake Bosumtwi, and their first settlement was Asantemanso, where their ancestors claim to have come from the ground.

The Asante were formerly Denkyera subjects until Osei Tutu, founder of the Asante Kingdom, ended Denkyera domination in 1695. After this, the Asante empire began to expand northwards and southwards.

By the beginning of the 19th century, peoples inhabiting an area larger than present-day Ghana, which extended into what is now Upper Volta, Ivory Coast, and Togo, were vassals of the Asantehene.

When the Portuguese, who were the first Europeans to arrive on the Guinea Coast, reached the area in 1471, the ancestors of present-day Ghanaians had recently arrived and were still continuing their migrations. The history of the territory that is now Ghana may therefore be conveniently dated from the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th century.

THE ARRIVAL OF THE EUROPEANS

The first Portuguese to land were João de Santarem and Pedro de Escobar. They found the region full of alluvial gold and named the country the Gold Coast. They made a fortune for their employer, Fernao Gomes, who was given the surname of da Mina in recognition of his services to Portugal.

But when the trading contract, which had been given him by the Portuguese king, expired in 1474, the Portuguese government itself took over the West African gold trade.

In 1481 the Portuguese sent out an expedition under Dom Diogo de Azambuja to build the fortress of São Jorge da Mina on the coast, where Elmina is now located. The Portuguese were opposed by the Fante inhabitants whose king, whom the Portuguese called Caramansa, had urged them not to settle on Fante land. His pleas were ignored, and eventually, the land was leased to the Portuguese for an annual rent.

The Portuguese also built forts at Axim (enlarged and strengthened in 1515) at the western end of the Gold Coast, at Shama, further east at the mouth of the Pra River, and at Accra, today the capital of Ghana, on the eastern part of the coast. With these bases, the Portuguese were able to monopolise the Guinea coast trade.

However, their monopoly was soon challenged by the French, the English, and the Dutch. The Dutch built forts at Mori and Butri in 1598, and later at other places, such as Komenda, trading in gold and slaves. In 1637 they captured Sao Jorge da Mina, better known as Elmina Castle, from the Portuguese.

The English built a fort at Kormantin in 1631, thus inaugurating their rivalry with the Dutch. The Portuguese left the coast altogether in 1642 after the Dutch had captured their only remaining castle at Axim.

The 17th and 18th centuries were a period of European rivalry on the Gold Coast. Since the Europeans depended for their safety and prosperity on the goodwill of the inhabitants, whom they had by no means conquered, they had to use diplomatic methods to win friends and allies.

The Africans did not feel inferior to them, but regarded them as ordinary human beings, and acted as their middlemen in all forms of trading. They forbade them to leave the vicinity of the forts to buy slaves or to hunt for them, and if any trespassed, they could be killed or sold into slavery.

The Dutch, who had supplanted the Portuguese, did not monopolise trade for long. The English, Swedes, Danes, French, and Brandenburgers (Prussians) soon challenged them, building more forts along the coast, and making alliances with the Africans.

The Swedes stayed for only a short period, being driven out of the country by the Danes in 1657. The Danes then enlarged the captured Swedish fort at Osu, which they renamed Chhristiansborg and made it their headquarters.

In 1662 the English formed the Company of Royal Adventurers of England Trading to Africa. It was granted a Royal Charter, giving it a theoretical monopoly of trade from Gibraltar to the Cape of Good Hope. The company proceeded to build Cape Coast Castle in 1662, and then constructed four forts or lodges along the coast in 1663.

This was the period of Anglo-Dutch rivalry, during which the Dutch beat the English and seized aII their forts except Cape Coast Castle. The company had to surrender its charter in 1672, but the Royal African Company was formed in the same year to succeed it. It bought Cape and Coast Castle, built James Fort in Accra in 1673, and established forts at Komenda and Anomabu.

The Portuguese tried to return to the coast in 1679. After the Danish governor of Christiansborg Castle had been murdered in an intrigue, they purchased the castle from his Danish murderer.

But they stayed there for only a few years before selling the castle back to the Danes again and leaving. By 1685, however, Christiansborg was the sole possession left to the Danes.

The French built a factory (i.e. a trading depot) at Komenda in 1688, but it was destroyed by the local inhabitants a few months later, after which the French also left. They returned a century later, in 1788, but stayed for only six years before abandoning trading on this particular part of the West African coast.

The Brandenburgers, from the principality of Brandenburg in northeast Germany, came to the western part of the Gold Coast in 1682. They built a fort named Gross Friederichsburg near Cape Three Points, as well as two other forts nearby, at Akwida and Takrama.

In 1708, however, the Africans harassed them into abandoning these forts. For some years Gross Friederichsburg was occupied by an African chief, John Konny (q. v.), until the Dutch took the fort in 1725. Another African, an Akwamu adventurer named Asameni (q. v.), had seized Christiansborg from the Danes some years earlier, in 1693. He had ruled it as governor for some months, in the name of Akwamuhene (ruler of the Akwamu people), before surrendering it back to the Danes for £1,600.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Europeans dealt primarily with the 14 small African states that were ranged along the seaboard, from the mouth of the Tano River in the west to the mouth of the Volta to the east.

These states were not unlike the Greek city-states of the 5th and 4th centuries BC, and their inter-relationships also had similarities to those of the Greek states. European contact with the larger African states in the hinterland was more infrequent. The principal inland states of which the Europeans were aware at this time were (from west to east) Aowin, Wassa (Wassaw), Denkyera, Asante, Akyem (Akim), Akuapem ( Akwapim) and Akwamu.

The European forts stood on land rented from local chiefs, and the written agreements regulating these arrangements were called Notes. The rent for Elmima castle was two ounces of gold a month, but this was increased to four ounces at the end of the 17th century.

The rent for James Fort, Accra, was also two ounces, and for Cape Coast and Anomabu was four ounces. Apart from the rent, some influential Africans were also paid stipends.

1600 to 1733

Between 1600 and 1733, the year in which the power of the Akwamu people was broken, the following peoples figured prominently in the country’s history: the Ga, the Akwamu, the Akyem, the Asante, the Ewe, the Dagomba, and the Gonja.

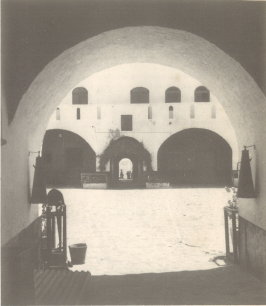

A 17th-century impression of Elmina Castle, built in 1482 by the Portuguese. From a medallion illustrating the 1658 Map “Africa Novo Description” by W. J. Blaeu, a Dutch Geographer.

THE GA

The Ga people probably moved from the Shai hills in what is now southeastern Ghana into the Accra area during the reign of Okai Koi, circa 1610-60. They are thought to have conquered the early Guan inhabitants of the area called the Obotu, and to have intermarried with them.

The Ga religion is a mixture of the religion that they had brought with them from the Niger basin and the aboriginal Guan religion. The Ga chiefs, like those of the Guan, were also priests.

THE AKWAMU

The Akwamu, from their capital at Nyanawase, some 20 mi (32 km) northwest of present-day Accra, tried to conquer Ga territory during Okai Koi’s reign. Because of the disunity in the Ga nation, and because of the headstrong nature of Okai Koi, the Akwamu easily defeated the Ga at the battle) of Nyantrobi in 1660, following, which Okai Koi committed suicide. The Accra plains became subject to the Akwamu, who subsequently received the rents from the European forts in the area from 1680 to 1730.

Akwamu history during this period is obscure. It would appear that the custom was to have two kings, an Old and a Young. The Young King, or deputy, commonly led the people in war, and probably sometimes succeeded the Old King on his death. The Akwamu conquered the Akuapem Hills, overlooking the Accra plains, and part of the region between the Kwahu Plateau and the Birem River (a tributary of the Pra) to the west.

Later the Akyem Abuakwa people migrated eastwards into the Akwamu area from Adanse, and are said to have been given land by the Akwamu. But the two peoples became enemies and fought one another in a series of battles, including the final crucial battle of 1730, about which Akwamu tradition is silent.

THE AKYEM

The Akyem nation is divided into three the Akyem Abuakwa, the Akyem Kotoku, and the Akyem Bosome. While all three groups are said to have migrated from Adanse, their early history remains obscure.

There were four kings of Akyem Abuakwa before Ofori Panin, the founder of the modern Abuakwa nation, came to the stool (i.e. the ruler’s seat of authority). Ofori Panin seems to have migrated from Adanse to Akyem during the wars between the Denkyera and Adanse, which took place in the latter part of the 17th century.

The Kotoku and Bosome groups, which were to establish themselves to the north of the Abuakwa, seem to have migrated eastwards after 1700. By 1730 they had encroached on Akwamu territory to such an extent that war was inevitable.

The war was fought to a conclusion in 1733, with the Akwamu being opposed by a coalition of Akyem Abuakwa, Akyem Kotoku, Agona, Obutu, Gomoa, Accra, and Fante peoples, in alliance with a Dutch contingent from Fort Crevecoeur in Accra.

The large number of groups who took up arms against the Akwamu provides some confirmation of the allegations that the Akwamu were bad neighbours, who resorted to violence, robbery, and kidnapping, as well as panyarring (a Portuguese word meaning to waylay, rob, and sell into slavery).

The dominant personality in the coalition was the Kotokuhene (ruler of the Kotoku), Firempon Manso. The war lasted more than a year until the Akwamu were decisively defeated near the banks of the Nsaki, a tiny river about 12 mi (19 km) north of Accra.

Abandoning their capital, Nyanawase, they fled eastwards across the Volta River. Accra then became independent of Akwamu, and the Kyerepon and Guan inhabitants of the state of Akuapem accepted Akyem overlordship.

Those Akwamu villages which had been inhabited by an Akyem population, led by the town of Asamankese, also accepted Akyem overlordship, and became part of the state of Akyem Abuakwa.

The people of Akuapem accepted Ofori Kuma, an Akyem general who had commanded their contingent against Akwamu, as their first ruler. In so doing they changed to the Akan tradition, since previously they had had priest kings.

THE ASANTE

Asante became a military power under Oti Akenten, whose rule began in about 1630, and who died in about 1660. He was succeeded by his nephew, Obiri Yeboa (ruled circa 1660-97), who continued Oti Akenten’s conquests, uniting the conquered territories into a confederation with its capital at Kwaman.

Obiri Yeboa was succeeded by Osei Tutu (ruled circa 1697-1731), founder of the Asante nation. Osei Tutu was helped in his task by Okomfo Anokye, a priest who used his magic powers and statecraft to introduce the Golden Stool as the soul of the Asante nation.

The capital of Asante, Kwaman, was renamed Kumase, and the Asantehene (ruler of the Asante), Osei Tutu, became first among equals in relation to the other chiefs of the Asante union.

A paramount chief

Asante was still subject to Denkyera when Osei Tutu became king. He fought against the Denkyera, however, defeating them first at the battle of Feyiase (November, 1701), and then at a battle on the Ofin River (another tributary of the Pra) the following year, at which Denkyera power was effectively broken.

During the war with Denkyera, the Asante captured the Note authorizing the Dutch to pay rent for Elmina Castle. This last development was to lead to1 the involvement of the Asante in coastal politics for the first time.

The Akyem nation had been allied to Denkyera during this war, and this led to further fighting between the Asante and the Akyem. The Akyem Kotoku were unable to pay the indemnity imposed upon them by the Asante, so Osei Tutu sent an expedition to enforce payment.

The expedition, however, was decisively defeated by the Akyem armies, Osei Tutu and his general staff were killed, and his army retreated to Asante. But the foundations that he and Okomfo Anokye had laid for the Asante nation endured.

Osei Tutu; whose death was commemorated by the Great Oath of Asante – the proscribed words “Koromante Memeneda” (meaning “Saturday at Koromante,” the day and place of his death) – was succeeded by his grandnephew Opoku Ware.

THE EWE

The Ewe-speaking peoples of Ghana and Togo, whose origin has been traced to Oyo· in Nigeria, claim to have migrated via Ketou in Dahomey to Notsie (Nouatja) in Togo.

From Notsie, the Ewe tribes dispersed to their present locations, this migration occurred not later than the early 17th century and possibly a century or more earlier.

According to tradition, there were three distinct groups of migrants from Notsie a northern, a middle, and a southern group. The northern group occupied an area stretching from Kpalime, in what is now Togo, down through the hills and valleys to the vicinity of Peki-Blengo, in what is now the Eastern Region of Ghana.

The middle group settled in the area surrounding Ho, in what is now the Volta Region, while the southern group migrated to the Anlo area on the southeast coast.

This last group was led by two captains, Amega Wenya and his nephew, Sri. When Wenya and his men came to the northern shore of the. Keta Lagoon, they settled there. Subsequently, Wenya’s sons, Akaga and Awanyedo, founded Keta, the seaport on the thin strip of land between the lagoon and the coast.

Sri’s party, meanwhile, crossed the lagoon and settled in the area between the western shore of the lagoon and the Volta River. Later, he rejoined forces with his father, and together they founded the Ewe state of Anlo, with Anloga (Awunaga), a dozen miles south of Keta, as its capital.

Not until the people of Anlo had fought and defeated their eastern neighbours, who owed allegiance to Dahomey, and later had fought the Accra settlers at Little Popo (modern Anecho) in what is now Togo, could the new state consolidate its position, however.

Despite occasional disputes with the Ga-Adangme people of Ada, on the right bank of the Volta at its mouth, over fishing rights on the river, the first half of the 18th century was reasonably peaceful.

After their 1730 defeat, the Akwamu moved eastward across the Volta, formed an alliance with the Ga-Adangme of Ada, and launched a joint attack upon Anlo in 1750. After that, the Anlo state faced a serious challenge and was troubled for a century by frequent wars and slave raids.

THE DAGOMBA

The early history of the inhabitants of the Northern regions of what is now Ghana is obscure. It is, however, known that the ancestors of the present ruling class of the Mossi, Dagomba, Mamprusi, and Gonja were male conquerors who entered the area from the north, intermarried with the local women, and imposed their rule, their customs, and sometimes their language on the original inhabitants.

Legend makes Tohajie, the Red Hunter, who came from a place eight days journey by caravan east of Bawku (in the northeast corner of what is now Ghana), the founder of the remarkable family whose members were to shape the history of the region. His grandson, Gbewa, or Bawa, migrated westward, settling at Pusiga, near Bawku, and founded a kingdom there.

Gbewa had eight sons, and a daughter, and was succeeded by the eldest, Zerile. After Zerile’s death, there was a dispute over the succession, and the family split up.

The oldest surviving brother, Sitobu, founded the Dagomba kingdom in what is now northeastern Ghana; the daughter, Yantaure, founded the Mossi kingdom in what is now Upper Volta; and the youngest, Tohugu, founded the Mamprusi kingdom, which extends along the northern extremities. of what is now Ghana.

In view of their common origin, the three kingdoms have frequently formed a triple alliance, and to this day remember their common origin. Sitobu is thought to have flourished around 1430. He was succeeded by his son, Nyagse, who conquered vast areas, and established Dagomba’s military power.

He killed the ten’ dana, or clan priests, of the conquered territories, and installed members of his family in their place. But since there were more clan priests than there were members of his family, the gaps were filled with military rulers, and the Dagomba state became a military autocracy. The religious functions of the tendana were, however, preserved by the new rulers, since they were considered essential to the stability of the new state.

THE GONJA

The first to check the Dagomba kingdom’s conquests were the Gonja, who attacked Dagomba in about 1620. The rulers of Gonja speak Gbanyito, a Guan language which is closely allied to the Akan group, and which seems to be older than Twi or Fante. It is the language of the conquerors of the area, however, since most of the population speaks Vagale.

The Asante call the Gonja Ntafo, or people from the north, a name given to the common ancestors of all the Akan tribes. The Gonja invasion of Dagomba was led by Sumaila Ndewura Jakpa.

His name is said to mean “Spear-holder,” while his middle name, Ndewura, appears to derive from the Akan word Wura, meaning “master.” Jakpa decisively defeated the Dagomba, who were led by their 11th ruler, Dariziogo, after which he installed his sons as rulers over the conquered kingdom.

Jakpa also founded a number of towns, one of which may have been Salaga, the Gonja market town, later famed as a slave market. At the time of Jakpa’s death, the Gooja empire stretched from Bole, near what is now the western frontier of Ghana, to Basari, in what is now Togo, a distance of about 200 mi (320 km).

The rivalry between Gonja and Dagomba lasted for a century, and during this time the Gonja may even have become overlords of the Dagomba. When Zangin was ruler of the Dagomba, however, and although peace prevailed, the Gonja, under the leadership of Muhamman Ware Kumpati (q.v.), launched an attack upon them. Under the leadership of Asigeli, who had succeeded Zangina on his death, the Dagomba defeated the Gonja in about 1720, and regained their freedom. This freedom was, however, short-lived.

After a dispute over the Dagomba succession had arisen, the Asante, under Osei Kwadwo (Kojo), (ruled 1752-81), intervened. The Dagomba, relying on their long swords, chain mail, and cavalry, had originally been able to overcome the aboriginal tribes of the region, but found themselves outclassed by the Asante guns. To this day they still call the Asante Kambonsi, or gun-men.

The Asante invaders easily captured the Dagomba capital of Yendi, and demanded an indemnity of 2,000 slaves. The Dagomba ruler, Gariba, could not supply so many, and it was agreed instead that the Dagomba should supply 200 slaves annually in perpetuity. This indemnity continued to be paid until the Sagrenti war of 1873-74, in which the British defeated the Asante.

1733 to 1826

THE ASANTE

Earlier, as we have seen, Opoku Ware, (ruled 1731-42), had succeeded to the Asante kingdom on the death of Osei Tutu. He extended Asante rule, defeating the Akyem nations in two campaigns, killing three Akyem kings, and capturing the Notes of the three forts at Accra – Crevecoeur (later, in 1868, renamed Ussher Fort), James, and Christiansborg.

When Kumase, the capital of Asante, was successfully attacked by the Sehwi (Sefwi), a people living to the west, Opoku Ware sent forces in pursuit of them as they returned home. Under the leadership of Amankwa Tia, the Bantamahene (the title for the Asante warlord who was also the chief of Bantama, a village near Kumase where the royal mausoleum is located), the Asante crushed the Sehwi army, annexed Sehwi, and renamed it Ahafo.

Opoku Ware later attacked and subdued two other states – Takyiman (Techiman), north of Kumase, and Gyaman, to the northwest.

Kusi Obodum, [ruled 1750-64], succeeded Opoku Ware, and defeated the Akyem states, which had allied themselves with Dahomey, succeeding in crushing them before the Dahomeyans could come to their aid. His subsequent attempt to punish the Dahomeyans, however, ended in disaster.

He was succeeded by Osei Kwadwo (1764-77) who, as we have seen, vanquished the Dagomba. Continuing the policy of imperial expansion. Osei Kwadwo fought against the Banda people to the northwest of Asante, although they were aided by the states of Gyaman, Denkyera, Wassa, and Kong, the last being a Muslim kingdom located on the northern uplands of what is now the Ivory Coast.

After initial reverses, Osei Kwadwo defeated his opponents, and annexed Banda and Wassa. An Asante official became the Asantehene’s representative among the Dagomba, although the Dagomba rulers continued to administer their country without interference from the Asante.

Osei Kwadwo also fought against the Akyem, who were allied to the Assin to the south, who, in turn, were neighbours of the Pante states. Osei Kwadwo had paid the Fante states handsomely to be neutral in the war, but the Fante took the money and broke their promise.

Osei Kwadwo swore to punish them later, but died before he could do so. A succession of rulers followed him. These were Osei Kwamina, who was deposed, Opoku Fofie, who died soon after his installation, and Osei Asibe Kwamina, later known as Osei Bonsu, who became Asantehene in 1800.

Osei Bonsu fought Gyaman and also Gofan – a state to the northwest of Asante across what is now the Ivory Coast border – defeating both of them. In 1805 he came into conflict with both the Pante and the British because of an internal dispute in Assin, in which one of the parties had sought the Asantehene’s intervention.

The circumstances were the following. After Asante arbitration had failed, the dispute led to a war in which the Asante defeated the forces of the main Assin faction at Kyekyewere (Chichiwere). After the defeat of the Assin, two of their chiefs took refuge in Pante territory, at Abora, near the coast. The Fante chiefs then met to decide what was to be done about the two men.

It was recognized at the time that the occasion was an historic one that would decide relations between the Asante and the Pante for years to come. In the event, the Pante chiefs decided to treat the two chiefs as suppliants, refused to resort to arbitration, and refused to allow the Asantehene to seize the men by force. Osei Bonsu therefore declared war on the Pante states.

He defeated them at Abora in May, 1806, occupying Korman tin on the coast, where the Dutch governor surrendered Fort Amsterdam to the Asante.

The Assin chiefs then sought help from Colonel George Torrane, the British governor of Cape Coast. Because the Cape Coast chiefs had promised to aid Assin, Torrane responded favourably to their request. But the Asante took the British fort of Anomabu, a short distance to the east of Cape Coast, after heavy fighting.

Torrane then sued for peace, met the Asantehene, surrendered one of the two refugee chiefs to him (the other escaped), and reached an accord with him. Although no formal treaty was signed in 1806, it was nevertheless agreed that the Pante states had become Asante subjects by right of conquest. The Asante, moreover, became entitled to the Notes of the forts on Pante territory.

The Asantehene left the coast to return home in 1807, and in 1809 the Pante, to reassert their authority, attacked their neighbours in Accra and Elmina.

The people of Elmina asked for help from the Asantehene, who in 1811 sent armies to both Accra and Elmina to fight the Fante. During this war, the Akyem Abuakwa revolted against Asante rule, and joined the Akuapem in fighting the Asante.

A combined force of Accra and Asante defeated the Fante at Apam, a coastal town halfway between Elmina and Accra. Asante power was making itself felt along the coast.

Cape Coast Castle, for more than 200 years the principal British stronghold on the Gold Coast. Built in 1662, it later became the capital of the Gold Coast until 1876, when the government moved to Accra.

CONSTITUTIONS OF THE AKAN STATES

It would seem appropriate at this juncture briefly to review the Asante constitution as it operated during this period. Indeed, not only the Asante, but the other Akan states, although non-literate, observed unwritten constitutions at this time. These constitutions, some of which are still operative today with certain modifications, resembled each other, and the Asante constitution may be taken as a typical example of them.

In the Asante constitution, the Asantehene was (and is) the head of the amanhene (paramount chiefs) of the union, and occupied the Golden Stool. He was the political and spiritual head of the Kumase division, in which he had rights over land and property. The next in importance to him was the Mamponhene (ruler of Mampon [Mampong], a town 30 mi [48 km] north-west of Kumase), who occupied the Silver Stool, second only to the Golden Stool. The Mamponhene was an independent omanhene (paramount chief), and not a feudal lord, so that the Asantehene had no rights over his lands and properties. Below these divisional heads were the adekurofo, or town and village chiefs.

Since ahemfo (Akan chiefs) were selected from certain royal families, the form of society may be regarded as aristocratic. Although the Asantehene was first among equals in relation to the other chiefs of the Asante union, and not a liege lord, the union constitution enjoined the wing chiefs (divisional chiefs with military duties) to swear allegiance to him and to keep their oaths. They recognised the right of appeal from their courts to his court at Kumase.

The amanhene had to attend the Asantehene’s Odwira festival (an annual yam festival, at which the ancestors’ spirits were propitiated, and the cohesion of the union upheld), helped to propitiate dead kings, and cleansed the nation from defilement.

They paid war taxes and other levies imposed by the Asantehene, and observed certain trade regulations made by him. Though in theory only those who enstooled chiefs could destool them, when the Asantehene’s powers increased in the-late 18th century, it was possible for him to get chiefs destooled.

The ahemfo were custodians of state lands. Lands acquired by conquest by any one of them were theirs by right. But none of them had the right to sell state land, whether inherited or conquered.

The amanhene had much say in foreign policy decisions, since they were responsible for the conquest of neighbouring territories. They could therefore influence the Asantehene’s foreign policy decisions, or even veto them. But in the domestic administration they were spectators rather than participants. They influenced domestic affairs by making suggestions which they had no power to press, since the Asantehene’s decision was final and not subject to veto.

Osei Tutu decided to increase the powers of the Kumase divisional ahemfo and so limit the great powers of the amanhene. The Kumase ahemfo became governors or viceroys of conquered territories. The Asantehene relied on them for the day-to-day administration of his division, as well as of the nation.

They soon became powerful political figures in the union, and some of them were outstanding generals. An omanhene who wanted to approach the Asantehene on some issue, generally passed through his friend, or adamfo, at Kumase.

Thus the Mamponhene had to pass through ‘the Bantamahene (ruler of Bantama) or the Kurontihene (captain general of the guards) of Kumase before he could get the Asantehene’s ear. The title of adamfo, however, was a courtesy title, and it was also lawful for any omanhene to meet the Asantehene alone to discuss his problems with him.

Those Akan states which did not form unions had amanhene who were independent of each other, and who had the right to make war and to conclude alliances. Such rights were, however, denied to the amanhene of the Asante union.

All the ahemfo could be autocratic, since their powers were ultimately based on military force. Since all the states were slave-owning, Akan society could not be democratic. But the fact that ahemfo could generally be destooled without bloodshed showed that there were constitutional checks and balances against extreme despotism.

The Asante method of ruling vassal states was to send an adamfo to each state to protect the Asantehene’s interests.

This regional or district commissioner did not rule the area directly, as a viceroy rules over a province or country, but allowed the Omanhene to administer his state while often taking sides in succession disputes or in intrigues. This kind of indirect rule often made it easy for the vassal states to revolt or to form alliances detrimental to the Asantehene’s interests.

THE BRITISH

In the years that followed the defeat of the Fante by the Asante at Apam in 1811 the influence of the British also increased on the coast.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the Fante, Accra, and Akuapem states concluded treaties with the British, the Dutch, and the Danes, and often submitted their disputes to the governors of the various European forts for arbitration, even though there was no question of any European power having jurisdiction over them.

The abolition of the slave trade by the British in 1807, however, meant a loss of revenue for Africans and Europeans alike. The Asante nation, in particular, resented the abolition.

In effect, several interests combined to continue the slave trade by stealth. This, in turn, led to pressure in Britain for a unification of Britain’s small West African settlements so that the slave trade might be more effectively suppressed.

Meanwhile, between 1817 and 1831, the British tried to pacify the coast, which had been unsettled partly by the abolition of the slave trade, and partly by the incursions of the Asante armies.

In pursuing this policy, the British attempted to conclude treaties with the Asante, but these treaties were only to lead to more misunderstandings.

The British government had decided in 1821 to annex the Gold Coast settlements to the British crown colony of Sierra Leone.

In practice, this meant that the African Company of Merchants which had hitherto represented British influence on the Gold Coast, was replaced by the governor of Sierra Leone as the source of British authority in the area.

THE BATTLE OF KATAMANSO

The governor of Sierra Leone, Sir Charles Macarthy, arrived in the Gold Coast in 1822, but by 1823 he had become embroiled in a war with the Asante that was to continue until 1826, even though Sir Charles himself was killed in battle and his forces dispersed in 1824.

In 1826 a new Asante army invaded the coastal region, but was defeated at the battle of Katamanso (Akantamasu), 15 mi (24 km) northeast of Accra, by a combined force of British, Accra and other Ga tribes, Fante, Denkyera, Akyem, and Akwamu.

The British name for this conflict was the battle of Dodowa, and as a result of it they acquired the lands on which their forts stood. But a peace conference called at Cape Coast in 1827 was unsuccessful, and although no significant fighting ensued, another four more years were to pass before a settlement could be reached.

1831 to 1901

THE BRITISH PROTECTORATE

After the victory at Katamanso, the British government withdrew its authority, and handed the administration of the British settlements on the Gold Coast over to a committee of merchants in London.

The committee appointed Captain George Maclean as governor, and he took up his duties in 1830. In 1831, together with the Fante, he concluded a treaty with the Asante which restored peace to the Gold Coast.

The Asantehene, Otumfuo Opoku Ware II, seated under a canopy of state umbrellas, and surrounded by gold regalia

In the 12 years which followed, his work laid the foundations for British rule in the Gold Coast, for he added executive functions to his judicial duties, and won the respect of the inhabitants. In 1843, however, the British Crown once more assumed responsibility for the British settlements, which were again made subject to Sierra Leone administration.

The British sphere of influence in the Gold Coast, known as the ‘Protectorate,’ was extended during Maclean’s governorship. A select committee appointed by the British parliament, and which in 1843 had praised Maclean’s administration, had recommended that the relation of the people of the Protectorate to the British Crown should be:

… not the allegiance of subjects, to which we have no right to pretend, and which it would entail an inconvenient responsibility; to possess, but the difference of weaker powers to a stronger and more enlightened neighbour, whose protection, and counsel they seek, and to whom they are bound by certain definite obligations.

THE BOND OF 1844

The new British governor, Commander H.W. Hill of the Royal Navy, in 1844 negotiated a Bond, which was signed by himself and eight chiefs, including those of Denkyera, Anomabu, Cape Coast, and Assin.

This document has been compared to Magna Carta for its effects upon the country throughout the subsequent colonial period. When the Gold Coast became independent as Ghana in 1957, the date of independence was fixed on March 6 to coincide with the date of the signature of the Bond. The Bond reads:

1. Whereas power and jurisdiction have been exercised for and on behalf of Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, within diverse countries and places adjacent to Her Majesty’s forts and settlements on the Gold Coast; we, chiefs of countries and places so referred to, adjacent to the said forts and settlements, do hereby acknowledge that power and jurisdiction, and declare that the first objects of law are the protection of individuals and property.

2. Human sacrifices, and other barbarous customs, such as panyarring, are abominations, and contrary to law.

3. Murders, robberies, and other crimes and offences, will be tried and inquired of before the Queen’s judicial officers and the chiefs of the districts, moulding the customs of the country to the general principles of British law.

Done at Cape Coast Castle before His Excellency the Lieutenant Governor, on this 6th day of March, in the year of our Lord, 1844.

Among traditional Ghanaian institutions is that of the linguist. This official is not an interpreter, but transmits speech between the chief and those with whom he is talking. Here the linguists of chiefs are seen in procession.

In 1850, the Gold Coast was again separated from Sierra Leone, and thereafter had its own governor as well as its own legislative and executive councils. In the same year, the Danes sold their forts to the British, and left the country, after which British jurisdiction extended as far east as Keta.

By this time more states had adhered to the Bond. The governor therefore decided to raise revenue for development, and met with an assembly of Fante and other Protectorate chiefs at Cape Coast to discuss how this might be done. (Later, a similar meeting was convened at Christiansborg, at which chiefs from Accra, Akyem, and Akuapem, as well as from the left bank of the Volta, agreed with the decisions taken at Cape Coast).

The Cape Coast meeting resolved itself into a legislative assembly “with full powers to enact such laws as it shall deem fit,” and declared that its enactment, sanctioned by the governor and approved by Her Majesty the Queen, should be held binding upon the whole of the population under British protection.

It was then resolved that a poll tax of one shilling a head should be imposed on every man, woman, and child in the Protectorate. The tax was to be collected by officials appointed by the governor, and not by the chief’s officers.

The proceeds were to be used to pay the stipends of chiefs and “to provide for the public good” of the people in education, in the judiciary, in communications, in medical aid, and in other ways.

These measures were to be enacted into law, and seemingly became binding upon the peoples of the Protectorate. But the governor had not realised that the chiefs had no constitutional right to bind their peoples to pay taxes without first discussing the proposals with their elders.

In addition, the people opposed the collection of tax by government officials. The tax proved difficult to collect, the assembly which originated it soon ceased to exist, and the British abandoned the tax altogether after 1861.

In 1853 the first Supreme Court Ordinance was passed, and courts were established by the British in the settlements to deal with civil and criminal cases.

In 1856, moreover, the British Protectorate was extended to include the former Danish Protectorates of Akuapem, Krobo, and Krepi (Peki). Akwamu also joined the Protectorate in 1886.

WESTERNIZING INFLUENCES

One of the effects of growing British influence was to promote the spread of literacy and education, even though the educators and missionaries were frequently from other countries.

It may therefore be appropriate here to review the development in literacy and western education in the country from the 16th down to the 19th century.

The African states of the region did not at that time have a literate class of educated citizens. The Asante nation had had a long association with Muslims from the north, but no Asantehene had ever trained Asante Arabic scholars, or established schools for Arabic or other studies.

The graphic arts were not studied, so that therefore no drawings or paintings by Africans depicting the kings, generals, and statesmen of the period from 1500 to 1800 have come down to us.

Christianity and literacy went together, and it was the missionaries who, uninvited, first introduced Western education into the country. But early efforts were sporadic and disconnected.

The first attempts at educating Africans of the coastal areas were made by the Portuguese in their castle school at Elmina. The first Catholic missionaries, who were Augustinians, came to Elmina in 1572, and then extended their work to Komenda on the coast, and Efutu further inland. Living conditions in the country were so bad, however, that the missionaries died within five years, and their work was abandoned. In 1638 two French Capuchin missionaries came to Axim, and were permitted to work there by the Portuguese.

This they did for a few years, and then left. At about this time, after the Dutch captured Elmina, a school for African and mulatto children was opened there in 1641 by two Dutch chaplains. It ceased to function, however, when the chaplains left.

A century later, in 1737, the Moravian Brethren (a Protestant communion, then based in Herrnhut, Saxony, in what is now East Germany) sent a missionary, Christian Protten, a mulatto from Christiansborg, to work in Elmina. Later he returned to Christiansborg, where he was a catechist from 1764-69.

Important precursory work among the Africans of the coast was also performed by the Rev. Thomas Thompson, who arrived in 1752. Thompson established the headquarters of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel at Cape Coast, and evangelized as far as Accra.

He sent Philip Quaque (Quacoe)d to prepare him for missionary work. Quaque returned to the Gold Coast in 1766, and worked as a teacher and minister for more than 50 years.

The Basel Mission

But missionary work which produced a lasting effect, and aided the intelligence of that elite which was eventually to lead the country to independence, began early in the 19th century. The Basel missionaries from Switzerland were the first to arrive, in 1828, and they were followed by the Wesleyans from Britain in 1835. But the Basel Mission encountered health problems, and several missionaries died within a few months of their arrival.

Eventually the mission decided to bring in black West Indians who could better withstand the climate. After this, the Bremen Mission arrived from Germany in 1847, the Catholics in 1881, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Mission (A.M.E.Z.) in 1898, and the Anglicans in 1906.

The first Basel Mission school had been opened at Christiansborg in 1843, and another, for the children of the West Indian missionaries, was opened at Akuropon (Akropong) in the state of Akuapem later that year.

Captain George Maclean, governor of the British Gold Coast settlements from 1830-43. After he had negotiated the Treaty of 1831 with Asante, his reputation as an impartial judge spread throughout the country, paving the way for an increase in British influence on the Gold Coast.

After this, Akuropon became a centre for pioneer educational work. In 1844 the Mission there opened the first school in the country to use Twi as the language of instruction, while in 1848 it founded, at the same place, a seminary that was to remain for the rest of the century the only institution of higher education on the Gold Coast.

The students were given practical as well as academic training, since, as catechists and pastors, they had to build their own houses, schools, and churches, and also establish farms and workshops. The myth propagated in the 20th century by some African nationalists that white missionaries gave Africans literary education and so prevented them from working with their hands is not substantiated by the mission history of the 19th century and the first two decades of the 20th.

The Mission did indeed, as it was expected to do, supply the colonial government with the majority of its clerks, but it also trained generations of artisans, who worked not only on the Gold Coast but all over West Africa, and as far away as the Congo. It is also to be remembered that the first roads in the eastern region of the country were made by the Basel Mission.

In addition to its other activities, the Basel Mission engaged in commerce and had a factory (trading post). It helped to stamp out traces of slavery by redeeming pawns (persons pledged into a state of semi-servitude as security for debt) and educating them.

It introduced new crops, and experimented with cocoa growing. It was a Basel Mission artisan, Tetteh Quarshie, a redeemed pawn, who brought cocoa pods to the Gold Coast from the island of Fernando Po in about 1878, setting an example which was to have an incalculable effect upon the country’s economy.

The first cocoa farms in Akuapem and Akyem were also established by African members of the Mission.

Both the Basel and Bremen Missions developed Twi, Ga, and Ewe as media of instruction, especially in the initial stages of education, and translated the Bible into these languages.

Literacy in Akuapem reached its height in the 20th century, mainly as a result of the efforts to encourage the use of Twi by the Rev. J.G. Christaller, with the aid of David Asante, Theophilus Opoku, and other pastors.

The use of Ga was encouraged by the Rev. John Zimmerman, who finished translating the Bible into that language in 1865, while the Bremen Mission encouraged the use of Ewe, and established an Ewe school in Germany for their pupils from Togoland.

The Wesleyans

The Wesleyan Mission, for its part, had to face the same health problems that had confronted the Basel Mission. The Rev. Joseph Dunwell was the first Wesleyan to begin work, arriving at Cape Coast in 1836, but dying within six months.

The work was carried on by Africans until the arrival of two missionary couples, the Wrigleys and the Harrops, who all died within a few months of their arrival.

Christian missions, such as the Basel and Wesleyan missions, played a vital role in national development. This picture shows the Methodist Church at Anomabu, with Bannerman House on the left.

The work would have ended all together but for the arrival in 1838 of a mulatto Thomas Birch Freeman, with his wife. Though Freeman’s wife died soon after arriving, he himself survived. In 1839 he visited Kumase, and established a mission there which endured until 1872. Freeman continued his missionary work up to the time of his death in 1890.

The Wesleyans worked among people who were acquainted with the English language, and so did not initiate much work in local languages.

Books were written in Fante, but they were not of the same high standard as those which had appeared in Twi, Ga, and Ewe. The full translation of the Bible into Fante was not to be completed until 1944.

But the Wesleyans educated most of the elite who fought for the rights of Africans. Several of the 19th century nationalists among the Fante began life as teachers and catechists in Wesleyan schools, then took to commerce, and finally entered politics.

Some had their children trained in English schools, and later entered them into such professions as law and medicine. Men like John Mensah Sarbah, the lawyer, Dr. J.E.K. Aggrey, the educator and nationalists like the Rev. S.R.B. Attoh-Ahuma, J.P. Brown, and J.E. Casely Hayford, all started as teachers.

NINETEENTH-CENTURY JOURNALISM

Journalism also played an important role in the political activities of the elite. The first newspaper to be established by Africans was the Accra Herald, later the West African Herald, founded in 1857 by Charles Banner-man in James Town, Accra.

The Christian Messenger and Examiner was established in 1859 by the Rev. T.B. Freeman and his associate, the Rev. Henry Wharton from Grenada in the West Indies. Also published during this period were the Christian Reporter, and Sika Nsona Sanegbale (the Gold Coast Chronicle), a Ga newspaper published by the Basel Mission.

The Gold Coast Times, which appeared every other week, was published in Cape Coast during 1874 and 1875 by James Hutton Brew (q.v.), its editor. Brew also published the Western Echo from 1885-87, with the assistance of J.E. Casely Hayford.

The Gold Coast Methodist appeared in 1885 for a year or two, and later, in 1894, the Gold Coast Methodist Times became famous under the Rev. Attoh-Ahuma’s editorship. Casely Hayford was connected with the Gold Coast Echo and the Gold Coast Chronicle between 1888 and 1894.

Other newspapers run by Africans were the Gold Coast Independent, Gold Coast Observer, Gold Coast Express, Gold Coast Aborigines (founded in 1898 by the Aborigines’ Rights Protection Society [A.R.P.S.], under Sarbah’s inspiration), and the Gold Coast Leader.

The Leader lasted from 1902 to 1933 or 1934, and was associated with J.E. Casely Hayford’s name. The Basel Mission started The Christian Messenger in 1883 under the editorship of the Rev. J.C. Christaller. It was written in Twi, Ga, and English, and is an excellent source book for the social and political history of the period. It is still run by the Presbyterian Church of Ghana.

ASANTE-BRITISH RELATIONS

Having thus glanced at the social context of developments during this period, we may return to take up the tale of relations between the Asante on the one hand, and their neighbours as well as the British on the other. These relations were the dominant theme in national history during the 19th century.

During the reign of the Asantehene Kwaku Dua I (1836-67), difficulties, which lasted from 1844 to 1853, arose between the Asante, and the British and the Assin, but war was averted. Between 1854 and 1862, the Asante nation remained at peace with its neighbours.

But trouble arose between the Asante and the British in 1862 after the British administrator, Richard Pine, had refused to surrender some refugees who had fled from Asante to Cape Coast. (At this time the British Gold Coast settlements were still under the authority of the governor of Sierra Leone, so that the highest British official on the Gold Coast held the title of administrator, and not of governor).

What Pine did not know, but which his British predecessors would have known, was that since the Asantehene had sworn the Great Oath of Asante to confirm his promise of safe conduct for the refugees, his word could be relied upon.

Anomabu, east of Cape Coast, has frequently figured in Ghana’s history, and was the birthplace of Dr. J. E: K. Aggrey (q.v.), the famous educator. Above is the courtyard of Fort William, Anomabu, built by the English in 1673-74.

As it was, Pine refused to accept the Asantehene’s promises. Finding himself thus opposed, the Asantehene invaded the coast in 1863, and defeated the allied forces ranged against him. After the Asante army had returned home, Pine wanted to invade Asante to maintain British prestige and to deter future invasions of the coast, but was prevented by the outbreak of disease among his troops.

Hearing this, the Asantehene commented sardonically that the white man had brought his cannon to the bush (i.e. the hinterland), but the bush was stronger than the white man. An attempt was made in 1865 to conclude peace, but was unsuccessful. Two years later, Kwaku Dua I died, and was succeeded by Kofi Kakari (1867-74).

The defeat of the coastal states by the Asante in 1863 and 1864 led the British to decide to limit their responsibilities in West Africa, and to aim at giving up their Gold Coast possessions altogether at a later date. A report by a British House of Commons committee stated:

“The object of our policy should be to encourage in the natives the exercise of those qualities which may make it possible for us more and more to transfer to them the administration of all the Governments”.

This and other statements in the report made the Africans assume that the British would indeed soon withdraw. The British authorities on the coast increased the alarm by announcing that if there was an Asante invasion, British troops would be used only to defend the settlements.

Body-guards of a chief

The last straw was the agreement signed between the Dutch and the British in 1867 concerning the exchange of certain forts. The intention was to end a situation in which the Dutch and British forts charging different trade tariffs were interspersed with one another along the coast.

It was therefore decided to divide the coast into two sections, a British and a Dutch, with all the British forts lying to the east of Dutch-owned Elmina, and all the Dutch forts lying to the west of it. But since the Africans living in the areas affected had not been consulted about this exchange, tensions arose.

Opposition was particularly strong in those states which opposed the replacement of the British by the Dutch because they had formed alliances with the British against the Asante, whereas the Dutch had remained neutral.

THE FANTE CONFEDERATION

The majority of the Fante states, feeling that the heralded British withdrawal would leave them defenceless against the Asante threat, decided to prepare for the future by forming the Fante Confederation at Mankesim, 20 mi (32 km) northeast of Cape Coast, in 1867. (Later, after the promulgation of its constitution in 1871, the British governor was to do his best to destroy the Mankesim Confederation.

He would arrest and imprison its leaders, although they would afterwards be released on the orders of the British Secretary of State for the Colonies). In particular, the confederation sought to force the people of Elmina to abandon their alliance with the Asante.

This led the Asantehene, Kofi Kakari, to invade the coast in 1869. The Asante, who were allies of the Anlo at the eastern end of the coast, were at this time fighting a war with the Krepi people located immediately to the north of Anlo. British attempts to end the war were unsuccessful. In the course of the fighting, the Asante captured two Basel missionaries, Friedrich A. Ramseyer and J. Kuhne, as well as a French trader, J. Bonnat.

They took their prisoners to Kumase as hostages, and used them for bargaining with the British. But when in 1872 the Dutch handed over Elmina and their other forts to the British and left the coast altogether because Asante-Fante conflicts had eliminated their profits, they left behind a thorny issue.

Although the Dutch had not recognised his claim, the Asantehene regarded Elmina as part of his dominion, since he held the Note for the castle, which was taken from the Denkyera in the 18th century. Now the British had succeeded the Dutch, and the issue was raised again. Diplomatic efforts were made to avert an open conflict between the Asante and Britain. They failed, and in January 1873 the Asante marched south and invaded Assin.

A general war with the Fante states followed. The Asante commander who, like his famous 18th-century predecessor, the conqueror of Sehwi, was called Amankwa Tia defeated the allied army which opposed him at a place called Fante Nyankumase. He then chased it towards Cape Coast, and defeated it again, this time decisively, at Jukwa, 17 mi (27 km) northeast of the British stronghold of Cape Coast.

THE SAGRENTI WAR

This defeat led the British to send reinforcements under Sir Garnet Wolseley (known to the Africans as ‘Sagrenti’). The resulting war became known on the Gold Coast as the Sagrenti War.

In October 1873 Sir Garnet took over both the civil and the military command. He then defeated the Asante army, and fought his way north to Kumase, after his ultimatum had been rejected by Amankwa Tia. Kumase was captured by the British, and the Asante Union began to disintegrate after the Treaty of Fomena, which ended the war, was signed on March 14, 1874, at Cape Coast.

The terms of the treaty included the payment to the British by the Asante of an indemnity in gold, the renunciation by the Asantehene of all allegiance from Denkyera, Assin, Akyem, and Adanse, and his abandonment of all claims to Elmina.

Kofi Kakari could not compel the breakaway states to return to the union, and was deposed after he had failed to end the secession of Asafo Agyei, the Dwabenhene (ruler of Dwaben, or Juaben, a state to the northeast of Kumase).

He was succeeded as Asantehene by Mensa Bonsu [ruled 1874-83], who tried to end Dwaben’s secession and restore the Gold Stool’s authority over its subjects. He defeated the Dwaben army and broke the power of that state. Some of the Dwaben survivors fled to Akyem Abuakwa and settled in Koforidua, a large town 40 mi (64 km) north of Accra.

Mensa Bonsu spent the years from 1874 to 1883 trying to win over the remaining secessionist states. He experienced the greatest difficulty with Adanse, which was recognized as an independent state by the British in 1876. Relations between the Asante and the British became strained in consequence, and an already powerful war faction among the Asante in Kumase became stronger. The British, however, took military precautions against any Asante attacks, and the Asantehene, hearing of these extensive preparations, sued for peace.

Secession disputes in the Asante Union added to its troubles. There was civil war and anarchy after Mensa Bonsu’s death in 1883, and no Asantehene acceptable to all could be agreed upon between 1884 and 1886.

The Adanse, aware of these difficulties, chose this time to plunder Asante territory, and killed a large party of Asante traders. The Bekwaihene (the ruler of Bekwai, one of the Asante Union states located to the south of Kumase), who was named Karikari, retaliated by killing some Adanse traders, which led to war between Bekwai and Adanse.

Karikari met with disaster at the outset, but the rest of the Asante Union came to his aid, defeated the Adanse army, and, in June 1886, drove the whole Adanse nation southward across the Pra River in search of British protection.

The installation of a Ghanaian chief. The chief, with sword in hand, swears an oath of allegiance to his people.

PREMPEH I AND THE BRITISH

In 1888, the British confirmed the installation of the new Asantehene, Kwaku Dua III, better known as Prempeh I, who was then aged 16. Prempeh had no sooner been enstooled, however, then he found himself obliged to fight a civil war to keep the Asante nation together.

Two of the union states, Kokofu to the south of Kumase and Mampon to the north of it, rebelled but were subdued. Mampon, however, then proceeded to ask for British protection. This was the heyday of the “Scramble for Africa,” for the British, after the West African Conference of colonial powers held in Berlin in 1884-85, had, like the other European colonial powers, embarked on a policy of colonial expansion.

In the Gold Coast region, the British saw the French in the Ivory Coast as their principal potential rivals, and decided to extend their empire beyond Asante to head off any French encroachments to the north.

The British therefore began to interfere openly in Asante’s internal affairs by agreeing to give protection to the Mamponhene (ruler of Mampon), Owusu Sekyere, as well as by offering protection to other states, and by taking the part of the Adanse refugees, despite Prempeh’s objections.

In December 1890, a British mission was sent to Kumase to offer Asante British protection. The Asantehene declined the offer, and the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Knutsford, censured the governor of the Gold Coast for his unauthorised action.

In 1892 the Asantehene’s attack upon and defeat of Nkoranza (a state to the north of Kumase which had declared its independence three months earlier), however, led to British intervention.

Timber ready for shipping at Takoradi Harbor. Built in 1928, this deep-water harbour replaced an old surf pool and enabled cocoa, minerals, and timber to be easily shipped abroad, laying the foundations for an era of prosperity.

This was because Atebubu, a neighbouring British protectorate situated to the northeast of Kumase, felt threatened, and asked for British aid. Prempeh judged it advisable to abandon any intention he may have had of attacking Atebubu after a British officer was sent there.

The British Colonial Secretary, Lord Ripon, then suggested in 1894 that the Asantehene should accept a British Resident in Kumase, and a stipend for himself and his loyal chiefs. Prempeh hesitated because the offer contained a threat that in the event of a refusal a rival claimant might replace him.

The Asante Union then sent a delegation to London to discuss the issue with the Colonial Secretary. But before the delegation reached England, the new governor, William Maxwell (term of office 1895-96), issued an ultimatum from the Colonial Secretary to the Asantehene which demanded that he should accept a British Resident forthwith.

The Asantehene asked for time, but the request was refused. The British had decided to invade Asante and to declare it a Protectorate.

The expedition, under Sir Francis Scott, with Major Robert Baden-Powell (later to found the Boy Scout movement) in command of local troops, crossed the Pra River, and took Kumase in January 1896.

Prempeh was then obliged to submit formally to the British by prostrating himself at the feet of Governor Maxwell and asking for the protection of the Queen of England.

He, his parents, some relatives, and a number of Asante nobles and chiefs, were then taken prisoner and sent first to Elmina, and then later to the Seychelles Islands in the Indian Ocean.

THE YAA ASANTEWA WAR

The deposition and exile of Prempeh I led to an uneasy peace. War broke out after the governor, Sir Frederick Hodgson (term of office 1898-1900), had gone to Kumase in 1900 to ask the elders to bring him the Golden Stool and give it to him to sit upon. Hodgson, thinking of the stool as a throne, did not understand that it was sacred, and was not to be sat upon by anyone under any circumstances.

This sacrilegious demand led immediately to the Yaa Asantewa War, named after the queen mother of Edweso (Ejisu), 10 mi (16 km) east of Kumasi, who was the moving spirit of the Asante at this time. But the Asante were finally defeated in the following year, 1901.

On January 1, 1902, Asante lost its sovereignty, being annexed by a British Order in Council, and placed under a chief commissioner, responsible to the British governor of the Gold Coast.

The Northern Territories, largely as a result of efforts made in the 1890s by a Fante surveyor, George Ekem Ferguson (q.v.), was also made a British Protectorate at this time, being administered by a chief commissioner responsible to the governor.

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

The Gold Coast Colony. The British did not withdraw from the Gold Coast as the Fante Confederation had feared. The defeat of the Asante in the war of 1873-74 had led Britain to declare the Gold Coast possessions a colony in 1874, and to separate its administration from that of Sierra Leone.

While imprisoned for demanding self-government for the Gold Coast, Kwame Nkrumah and his Convention People’s Party (C.P.P.) won the February 1951 election. He was then released from prison to become Leader of Government Business. Here he is seen leaving prison, surrounded by his supporters.

The Gold Coast Colony thus had its own governor, and executive and legislative councils. The British settlement of Lagos, in what was later to become Nigeria, had continued, however, to be administered from the Gold Coast until 1886, after which it became a separate governmental entity.

Other developments, that were to have a long term effect upon the country’s future, also took place. In 1876 the capital of the Colony had been transferred from Cape Coast to Accra.

In 1888, John Sarbah, a Fante merchant whose son was later to become a renowned nationalist lawyer, was appointed as an African member of the Gold Coast Legislative Council. Town councils for Accra, Cape Coast, and Sekondi – the latter a port on the western part of the coast through which gold was shipped overseas – were established in 1894.

With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, further territory came under Gold Coast jurisdiction. After the defeat of the German forces by Allied troops in the neighboring colony of Togoland, the colony was arbitrarily divided between Britain and France, and the British sector was administered as a part of the Gold Coast.

CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS

1916-46. In 1916 the Gold Coast was given a new constitution – named the Clifford Constitution, after Sir Hugh Clifford, governor from 1912-19. The membership of the Legislative Council was increased from 9 to 22.

There were 12 official and 10 unofficial members. Seven Africans, including four chiefs, were unofficial members, and three Europeans represented commercial, banking, and mining interests.

In 1925 the Guggisberg Constitution, named after Sir Gordon Guggisberg, governor from 1919-27, enlarged the legislature, to consist of 15 officials and 14 unofficial members, 6 of whom were paramount chiefs elected by the Eastern, Central, and Western provincial councils of paramount chiefs.

In 1927 the Native Administration Ordinance, which strengthened the authority of the chiefs, was passed. In 1935 the Executive Council of the Colony was empowered to act for Asante and the Northern Territories. The Asante Confederacy was restored in the same year.

Later, in 1942, Nana Ofori Atta I, the paramount chief of Akyem Abuakwa, and Sir Arku Korsah, a barrister, were appointed as the first African members of the executive council.

An attempt during 1942-43 to separate Asante from the Colony by passing the Ashanti Advisory Council Ordinance was blocked through the efforts of Dr. J.B. Danquah, who persuaded the Asantehene to ask for a single legislature for Asante and the Colony.

This was eventually granted under the Burns Constitution of 1946, named after Sir Alan Burns, governor from 1942-47. Considered by several people to be advanced for its day, the new constitution made the Gold Coast the first colony in tropical Africa to have an elected unofficial majority.

The Legislative Council now had 31 members with the governor as president. There were 6 ex-officio members, and 24 unofficial members, 18 of whom were elected, and 6 nominated.

The governor had reserve powers to veto legislation, and the British parliament retained ultimate responsibility for the Colony. Three Africans were appointed to the Executive Council.

TOWARDS SELF-GOVERNMENT

In February 1948 riots broke out in various parts of the country to protest against (1) the high cost of living, (2) the government’s insistence on the compulsory cutting down of cocoa trees affected with the swollen shoot disease, and (3) grievances held by the youth of the country and by ex-servicemen who had just been demobilized after World War II.

The United Gold Coast Convention (U.G.C.C.), a political party seeking self-government by constitutional means, and which had been founded in 1947 by Dr. J. B. Danquah, took advantage of the situation. The British responded by appointing an investigatory body, the Watson Commission, which made recommendations which led to the appointment of the Coussey Committee, named after Sir Henley Coussey, an African judge.

The Coussey Committee, in turn, made recommendations which were accepted by the British and formed the basis for the 1951 Constitution, which represented a giant step forward towards self-government.

The ensuing elections were won by the Convention People’s Party (C.P.P.), founded in February 1949 by Kwame Nkrumah, a young nationalist politician who had recently returned from the United States, and who had broken away from the U.G.C.C.

In February 1951, the C.P.P. formed a government, with Nkrumah as Leader of Government Business. A ministerial form of government was instituted, and the Legislative Council elected its own speaker. The country as a whole was represented in the legislature.

The governor, however, still retained his reserve powers. In 1952 Nkrumah was appointed prime minister by the governor.

In 1954 yet another constitution came into force. Under the provisions of the new constitution, ex-officio members were excluded from the Executive Council.

The cabinet became responsible to the Legislative Assembly, and consisted of a minimum of eight parliamentarians appointed by the governor on the advice of the prime minister. The governor retained responsibility for defence and external affairs, and also retained his reserve powers.

The prime minister assigned portfolios to ministers. The legislature consisted of the speaker and 104 members, all elected by universal adult suffrage. There were no representatives of the provincial councils of chiefs. Elections under the new constitution were held that same year, and were at once won by the C.P.P. under the leadership of Nkrumah.

The opposition to Nkrumah had led to the formation of the National Liberation Movement (N.L.M.) in 1954. Based in Asante, the N.L.M. demanded a federal form of government which would give autonomy to the various regions.

Constitutional conferences held in 1956 failed to resolve differences between the C.P.P. and the N.L.M. The British government therefore decided that there should be a general election in July of that year, and that the party which won the majority would lead the country to independence.

The C.P.P. won the elections, but the opposition, led by Dr. K. A. Busia, continued to press for constitutional changes. Agreement was reached when Mr. Alan Lennox-Boyd, the British Colonial Secretary, presented the parties with a compromise constitution.

Meanwhile there remained the question of the future of British Togoland, adjoining the frontier of the Gold Coast.

It had become a League of Nations Mandated Territory in 1922, and a United Nations Trust Territory in 1946, continuing under British administration throughout. In 1956 the United Nations held a referendum in the territory to decide whether it should retain its status as a United Nations Trust Territory, or whether it should merge with the Gold Coast.

The majority of the population voted that it should merge, which it did, shortly before the independence of the Gold Coast.

INDEPENDENCE AND AFTER

Independence came on March 6, 1957, on which date the new state of Ghana became a British Dominion, with a governor-general representing the Queen, who was the head of state. The prime minister held all the reserve powers formerly wielded by the governor, and the British governor-general was obliged to act on the prime minister’s advice.

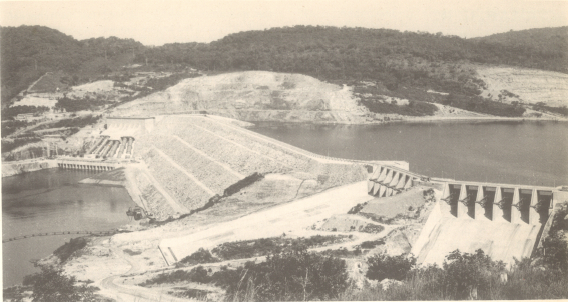

The Volta Dam, more correctly known as the Akosombo Project, which supplies the greater part of the electricity used in Ghana.

In 1958 the Nkrumah government abolished the Regional Assemblies, the role of which had been in dispute between the C.P.P. and the N.L.M. In the same year, the Ghana parliament adopted the controversial Preventive Detention Act, which facilitated the imprisonment of political opponents of the government.

In April 1960, a new republican constitution was submitted to a plebiscite, while at the same time two candidates for the presidency, Nkrumah and Danquah, sought election at the same time. Nkrumah won by an overwhelming majority, and became president on July 1, 1960. The constitution gave the president powers to legislate above the heads of parliamentarians by “legislative instrument.”

It also made provision for Ghana to surrender its sovereignty in favour of African unity. Judges could be removed only by parliament, but the chief justice as head of the judiciary could be removed by the president. In 1964, a national referendum approved proposals that (1) The C.P.P. should be the only lawful party, and (2) that the president could remove any judge from the supreme court.

In 1965 a single electoral list prepared by the C.P.P. was accepted without voting, and parliamentarians were selected for the National Assembly. There had been no elections since Ghana became independent, except for the post of president in 1960.

In that same year, 1965, Nkrumah was re-elected as president. An amendment to the constitution stipulated that any future prospective candidate for the presidency would have to be approved by the chairman of the C.P.P.

On February 24, 1966, Nkrumah, who was travelling abroad, was overthrown by a military coup led by Col. E. K. Kotoka , and the constitution was abolished. A National Liberation Council (N.L.C.) of soldiers and police officers was established by proclamation to run the affairs of Ghana, under the chairmanship of Maj. Gen. J. A. Ankrah.

In 1967, an executive council consisting of civilian commissioners and members of the N.L.C. was established, as well as a National Advisory Council. After a constitutional commission had met and made recommendations, its report was considered by a constituent assembly, which promulgated the constitution of Ghana’s second republic in 1969. General elections were held in the same year, and were won by the Progress Party. Dr. K. A. Busia was appointed prime minister, while the president’s duties were performed by a commission of three under the chairmanship of Brig. A. A. Afrifa.

The following year Mr. Justice Akufo-Addo was elected president, and the presidential commission was dissolved. In 1972, however, the government of the second republic was overthrown by a military coup led by Lt. Col. I. K. Akyeampong, and a National Redemption Council was established by proclamation.

This would later be transformed into the Supreme Military Council (SMC). Following this, Ghana was under military administration for a number of years, during which time the country’s political system and leadership changed frequently.

In 1978, Lt. Gen. Frederick Akuffo, Acheampong’s deputy, removed him from power and became the head of state. In June 1979, Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings led a military uprising against the Akuffo government.

This led to the formation of the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC). After a brief reign under Rawlings’ leadership, the AFRC ceded control to a civilian administration. After the AFRC handed over power, democratic elections were conducted, and the People’s National Party (PNP)’s Dr. Hilla Limann was elected president.

The Third Republic officially began with this. This marked the beginning of the Third Republic which started from September 24, 1979 until December 1981 when Dr. Hilla Limann’s government was overthrown by Rawlings’ second coup d’etat.

This led to the establishment of the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) with Rawlings as its head. Jerry Rawlings’ PNDC military Rule lasted for a decade, during which time the country underwent significant political and economic changes.

Multi-Party Democracy.

In 1992, Rawlings initiated a transition towards multi-party democracy. This included the lifting of a ban on multi-party politics. A new political party, the National Democratic Congress (NDC), formed by Rawlings and his PNDC won the presidential elections.

Rawlings therefore became the first president of the fourth republic and was subsequently re-elected in 1996 for another four-year tenure.

The New Patriotic Party’s (NPP) John Agyekum Kufuor won the presidential election held in 2000, ushering in the Fourth Republic’s first orderly transfer of power between political parties. Kuffour was re-elected in 2004 for a second term in office.

During his two stints as president, Kufuor carried out a number of social and economic changes. In 2009, John Atta Mills of the National Democratic Congress (NDC) was elected president after a closely contested election. He became the third president of the fourth republic. President Mills would be succeeded by his Vice, John Dramani Mahama, to serve the remainder of his term after he passed away on July 24, 2012.

John Dramani Mahama was subsequently elected for his own term as president in 2012. The next election in 2016 was won by Nana Addo Dankwah Akuffo-Addo who was re-elected in 2020 for another four-year tenure.