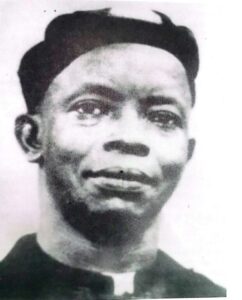

KAI, TONGI

- 8 Min Read

Kai Tongi (?-1973) was a paramount chief of Kissi Tongi in Kailahun district in Eastern province, Sierra Leone from 1942 to 1952. During his brief ten-year reign he invigorated his backward chiefdom with new life, rebuilding the capital, reforming agricultural methods, and building up a formidable football team. His despotic methods of ruling, though often effective, finally caused a revolt among his people, after which he was deposed.

PHOTO CAPTION: Kai Tongi. SOURCE: EA Library

His grandfather, Kai Kai, had been chief of the small state of Kissi Tongi during the last quarter of the 19th century. When Kai Londo was elected king of Luawa, today the largest chiefdom in the Kailahun district, at the Gbondu conference of chiefs, thereby becoming ruler over an enlarged Luawa state, he used force against those states that would not immediately recognise his supremacy. But Kai Kai came of his own free will to Kailahun, Kai Londo’s capital, and voluntarily agreed to “sit under him.” In this way, Kissi Tongi became a province of Luawa.

Kai Kai’s son, a great warrior who exerted powerful influence over neighboring Kiss states, persuaded Kissi Tenge and Kissi Kama to come under the ruling of the greater Luawa state, by which services and tribute were rendered by these states to Kailahun, the capital. In 1916, however, the relationship was altered.

The Luawa ruler, Boakei Kundeh, who had succeeded in antagonising the Kissi sub-chiefs in particular, was deposed, and the administration was decentralised to give greater autonomy to the Kiss areas, although appeals from Kissi courts as well as tribute still went to Kailahun. This was the political position when Kai Tougi was elected paramount chief in 1942.

In 1951, Kai Tongi, whose father was the warrior and ruler Koli Tongi, entered Bo government school, established in 1906 for the sons and nominees of paramount chiefs. After graduating in 1924, he entered the agricultural college at Niala, Moyamba district, Southern Province, where he showed marked athletic ability.

Leaving Njala, he was employed by the Agricultural Department but lost his job in the retrenchments caused by the Great Depression. Because of his unusual abilities, he was soon re-employed as a quarter-master’s clerk. He also made his mark as a sportsman, in cricket as well as football, and became a member of the Royal West African Frontier Force cricket and football teams.

In 1938 when Kai’s elder brother Ansuma, chief of Benduma section of Kissi Tongi, died, he returned home to take his place at the request of the people. A few years later the paramount chief, Foloba, died and in December 1942, Kai Tongi was elected paramount chief of Kissi Tongi.

Though Kissi Tongi at this time was poor and backward and suffering from the after-effects of famine, Kai was determined to transform his chiefdom into a model state, by force if necessary. He took up his new functions with energy, one of his first constructive steps being to stop tribute and appeals going to the Luawa court. As a paramount chiefdom, he held that Kissi Tongi should not be subject to any other chiefdom. In his determination to infuse life into the society, he decided on a new site for his capital, Buedu, declaring the old site to be unhealthy. The new town was planned on a grid system.

Kai carried out a thorough survey on the main streets basing his survey on a system of compounds, each compound measuring 60 feet by 80 feet and comprising a “modern rectangular” dwelling house (traditional round houses were forbidden), a kitchen, and a lavatory. To ensure that the old site was abandoned, Kai Tongi made it an offense either to erect new buildings on it or repair old houses.

He marked out places for public works to be carried out by communal labor from the whole chiefdom, building a market, a mosque, a church, a school, and a hospital. And he was insistent on high standards of sanitation, decreeing that all houses were to have a proper sewage system and must be well-ventilated.

Though his practical measures were progressive, Kai’s political methods were not enlightened. He came to be regarded as despotic by many people, not least his subjects. Obsessively concerned with hard work, he stopped the use of hammocks for relaxation as it encouraged laziness.”

His concern with morality, dress and personal conduct was equally intense, and led to stringent measures, such as corporal punishment administered to anyone appearing in the capital with the body exposed, as was the custom for farm-workers.

The communal shop, which he set up to provide the basics of modern living and in which all his subjects had to sell their goods, also included a tailoring section. This was to ensure that scantily clad farmers coming in to sell their produce would return properly dressed, after being flogged and forced to buy clothing!

By sheer force of personality, Kai Tongi in 1946 persuaded the army at Moa Barracks, at Daru in the Kailahun district, to sell him a used generator for £800 which he used to provide electricity for Buedu, thus making it one of the first provincial towns in Sierra Leone to have an electricity supply. Bo, the provincial capital, was only in the process of having electricity installed at the time.

Visiting Buedu a few years after Kai Tongi had built it, a British traveler recorded: “It is laid out on sound principles of town planing, each house in its own compound with a separate latrine, the roads broad and awaiting only the growth of young trees to become shady boulevards. And it is lit by electric light from Buedu’s own power station. Schools, cemented wells, and dispensaries meet every requirement of welfare and health planning.”

As an agriculturist, Kai was concerned to increase the productivity of his chiefdom and introduced extensive programs using new agricultural methods. Every adult male was forced to work a farm of his own as well as the communal family farm.

He insisted on swamp rice farming and actively encouraged the growth of cash crops, leading the way by establishing the largest cocoa and rice farms as well as an extensive poultry farm and orchard. In line with his insistence on hard work from all his followers, his wives, usually class in uniforms, worked long hours daily on his farms.

Not only in economic affairs but in social life as well, Kai was immensely active. He organized the first known dance troupe in the region, called “Kai’s dancers.” This troupe, a gift from a Gbandi chief in Liberia, became famous, accompanying Kai wherever he went. It specialised in a particular kind of display known as “Fango Loli”, and by bringing both the chiefdom and its ruler admiration and respect, added to his sense of overweening self-importance.

Still maintaining his keen interest in sport, Kai encouraged football to an unprecedented degree. The team he built up was virtually invincible in Kailuhun district. On one occasion, as a gesture of encouragement and the show that he was in earnest, Kai had a football field constructed in seven days.

When the Protectorate Assembly was established in 1946 as a debating forum for Protectorate interests Kai Tongi was elected as a member. As the moving spirit behind the modernisation of Kissi Tongi he had antagonized a number of people, including a district commissioner, for he would allow no one to stand in the way of the progress which he forced on his subjects. The demands he made for unpaid labor for his extensive farms were the source of bitter discontent.

Matters came to a head in 1951 while he was attending a Protectorate Assembly meeting in Bo. His subjects revolted and accused him of demanding labor without remuneration; of holding court sessions at night; of imposing extortionate fines and levies, and of insisting on compulsory buying and selling at the communal store. Although Kai Tongi employed a solicitor, in the subsequent enquiry he was found guilty and deposition was recommended, although even in colonial circles there were qualms about taking such a step.

True to his nature, Kai refused any offer of a job after his deposition but moved from Buedu to Freetown where he set himself up as a private building contractor and remained till his death in 1973.

One of the most dynamic rulers in mid-20th century Sierra Leone, his importance should not be underestimated. As the author of the Combey Manuscript observed in 1948: “As an agriculturalist, Kai Tongi has freed his people from the threats of malnutrition and poverty. While as a psychist he has infused into them new life and strength… Buedu once loathed by many, detested for its unsanitary state, has loomed out as a center for a holiday resort for all sorts of conditions of people… All go in praise of Kai Tongi, the miraculous reformer of the Protectorate age.”

This observation is not exaggerated. Although Kai Tongi died two decades after his overthrow, his rule is remembered with nostalgia by the people of Kissi Tongi, while lasting testimony to the achievements of his ten years of rule is still evident in that state.

ARTHUR ABRAHAM