A HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

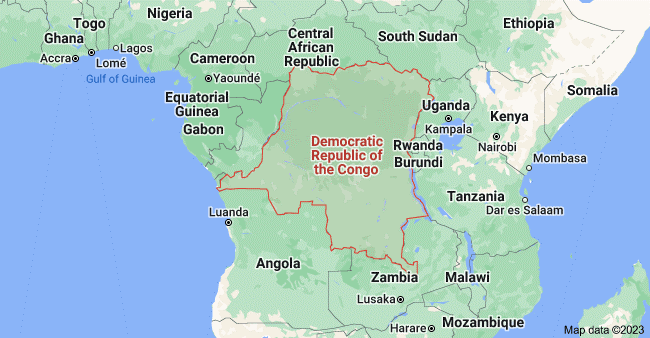

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) RC, formerly known as Zaire, is located in Central Africa. To the north, it is bordered by the Central African Republic and Sudan; to the east, by Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania; and to the south by Zambia and Angola.

Its territory of 2,344,885 sq km (905,365 sq mi) is situated in the vast basin which contains the Zaire (Congo) River and its numerous tributaries. The river takes its course almost entirely within Zaire.

It rises in Shaba region, in the southwest, after which it forms a huge arc, passing successively through the regions of Kivu, Haut-Zaire, Equateur, Bandundu, and Bas-Zaire, before flowing into the Atlantic Ocean.

The central basin, which lies across the Equator in the heart of the country, is almost entirely covered with thick forest. Savanna (tropical grassland) zones extend both north and south from this forest.

It is principally in these savanna regions, as well as in the Great Lakes region to the east, that the greater part of the country’s population, which in 1974 was estimated at 24,224,000, is settled.

THE PEOPLING OF ZAIRE

This vast territory, drained by many rivers, has without doubt been inhabited by human populations for centuries. Several prehistoric industrial sites have been identified within the territory of Zaire or in its surroundings.

Archaeologists have unearthed several vestiges of human activity which reveal and confirm the existence of all the stages of prehistoric evolution in the region. The first of these, the Earlier Stone Age, which may have lasted until about 55,000 BC, is represented by the Oldowan and the Acheulian (Chellean) cultures, of which traces have been discovered not far from Zaire.

Then the Middle Stone Age, which emerged in about 40,000 BC and lasted to about 8,000 BC, was represented by the Lupembian (Lupemban) tradition.

This, in turn, was followed by the Recent Stone Age, represented by the Tshitolian tradition. Part of the present population, notably the pygmies, may trace its origins to that archaic era of stone-age industries. Archaeologists attribute to them the industries which flourished in the Stone Age.

The principal activity at that time consisted in hunting and gathering, a social and economic phase which preceded the emergence of agriculture and stock-raising. Effective food gathering demanded considerable botanical knowledge so that the inhabitants could use effectively the plants found in the country.

The transition from food-gathering to agriculture probably took pace by progressive steps, beginning with the necessity of protecting and sometimes transplanting those forest species which had been identified as being of interest to man. Similarly, hunting could not be practiced without some knowledge of zoology and technology.

The original inhabitants of the region were therefore not uncultured nor unresourceful when the Bantu entered central Africa from the north and west, spreading out over its savannas and into its forests. Migrating probably in the first centuries of our own era, the speakers of the Bantu tongues began to occupy the territory that corresponds to present-day Zaire, decimating and absorbing the original inhabitants.

Some of the survivors of these original pygmy groups sought refuge in the ecologically inhospitable forests of the central basin where, independently of one another, they still subsist in separate “islands.”

The Bantu were the carriers of several revolutionary innovations, notably new crops and ironworking. Although rudiments of iron technology probably were not unknown previously, they offered major technological advances affecting food production and military effectiveness.

Agriculture, scarcely known before the Bantu arrived, henceforth began to spread and diversify as the Bantu speakers introduced cereals indigenous to West Africa, and bananas and yams from Southeast Asia.

The different waves of migrating peoples pushed into practically every region of present-day Zaire. The first migratory movements, which formed the basis of settlement, were followed by numerous internal relocations.

It appears certain that these populations initially settled in the savanna, or on the edge of the forests. This last zone was particularly attractive, for it permitted people to obtain forest products without experiencing the problems of living within its confines.

Traces of culturally and technically advanced societies, dating from as early as the year 800 AD, have been identified in the southern savannas and probably existed throughout DR. Congo. This, at least, is what has been deduced from the findings of excavations at Katoto and at Sanga in the vicinity of Lake Kisale, in southeastern Zaire. The discovery of copper crosses dating from this period not only in Zaire, but even as far away as the shores of the Indian Ocean shows the existence of long-distance commercial links. Cowrie shells and glass beads found in Sanga graves are further evidence of some coastal ties.

DR Congo River, 4,700 km (2,900 mi) in length, runs in a huge arc through Zaire. Here Wagenia fishermen are seen hauling in a catch from its waters.

Since there was adequate space for expansion and development, the various Bantu peoples were able to secure territories for themselves and develop as identifiable ethnic groups.

Distance and prior linguistic differences were factors in this process of differentiation. Exogamous villages and families, speaking the same language, exchanged wives within a limited geographical area, thus reinforcing the linguistic, agricultural, religious, and social unity of a given region.

In time, some groups, especially in the southern savanna, developed political structures unifying them under a common chief or king. In the forest, however, many peoples preserved their similarities through trade and fishing relationships. A few ethnic units maintained their cohesiveness through age-sets or esoteric secret societies which linked the leaders of politically unrelated villages.

In spite of diversification, the lines between ethnic groups were not rigid. Trade, intermarriage, resettlement, conquest, and cooperation all promoted cultural exchanges and borrowings. As groups merged, reformed, grew, or decreased, DR Congo’s ethnic mosaic resembled a gradually turning kaleidoscope rather than a fixed map.

THE CIVILIZATIONS OF ANCIENT ZAIRE

The period beginning around the year 1000 AD was a time of consolidation after the various peoples had settled in their specific territories. It was to lead to the development of several political micro-societies which may best be described as “chiefdoms.”

These constituted, in effect, the fundamental units upon which political systems of wider scope were erected. Ancient Zaire, thereafter, developed as an area in which some small existing groups became the subjects of powerful political kingdoms.

It was essentially in the savannas where communication was easiest, trade most advantageous, and the new agriculture most adaptable that the first states appeared. Most frequently these new state structures linked together previously autonomous and decentralized peoples.

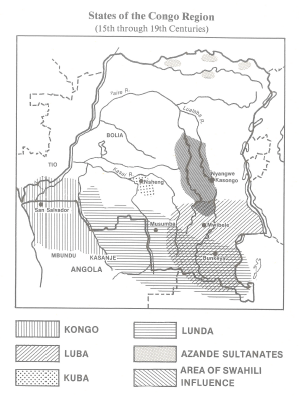

At least from the 10th century until the 18th century, what is now Zaire appeared as a confederation of several regions which gave birth to a number of states. One such region was located near Malebo Pool (former Stanley Pool). With its influence spreading as far east as the limits of Kasai, this nucleus gave rise to the coastal kingdoms of the west: Kongo, Kakongo, Ngoyo, Ngola, and Makako.

A second nucleus, less well known was located near Lake Mai Ndombe (formerly Lake Leopold II) to the northeast, where the centralized states of Bolia and Ntomba originated.

The Kuba kingdom, which emerged to the south of this region, owed its existence to influences both from the west and the north. A third area, centered around the lakes of Shaba (formerly Katanga) was to be the base of the prestigious Luba and Lunda empires.

Although mostly situated outside Zaire, another nucleus developed near the Great Lakes of East Africa, giving birth to the Ruanda, Burundi, and Buganda realms. The centralized state of the Shi of Kivu, in Zaire, also owed its origin to this source.

The kingdoms of ancient Zaire all stemmed from clearly defined sources, but each had its own particular evolution. The various kingdoms did not all originate in the same period.

Chronologically, the realms of the west coast were the most ancient. In the 15th century, the kingdom of Kongo, was at its zenith, enjoying remarkable prestige. The Lunda and Luba empires, on the other hand, did not reach a similar period of development until, at the earliest, the 16th and, more likely, the 17th century.

But the kingdom of Kongo and the states situated around it (Ngola, Matamba, Kakongo, Loango), were also the first to be confronted with the problems of the intrusion of the Europeans. In 1482, the caravels of King Joao II reached the shores of Kongo for the first time, and the Kongolese had the opportunity to meet with white men. When a second fleet of boats appeared, several Kongolese, thanks to a misunderstanding, were taken to Portugal as hostages.

This was the first time that the Kongolese were able to witness, at the source, the marvels of the technology that was beginning to flourish at the time of the European Renaissance. The account given by the hostages after their return to Africa in 1487 greatly impressed the Mani Kongo (king of Kongo) and his court.

The king, supported by the majority of the aristocracy, tried to benefit from these technological developments and asked for carpenters and masons from Portugal to build impressive state buildings. He also asked to be baptized so he could share that supernatural force which had created such wonders.

Subsequently, however, king Nzinga Nkuwu, who had himself witnessed the first Portuguese landing, felt he had lost something by converting to Christianity. He, therefore, renounced his baptism, while at the same time accepting acculturation, which, in any case, was advancing rapidly within his kingdom.

His successor, Mvemba Nzinga, who, in imitation of the reigning Portuguese monarch, had been baptized with the name of Afonso, was even more attracted by the prospects of modernization.

Hoping to modernize his realm at all levels Afonso reorganized the political establishment and the court, promoted Christianity on a wide scale, and launched a campaign for giving religious instruction to the ruling elite.

Several Kongolese young people were sent to study in Portugal while Portuguese professional men and artisans-including architects, doctors, pharmacists, cobblers, and tile-makers-were encouraged to settle in Africa.

Acculturation, however, never proceeded in a spirit of equality and cooperation, for the Portuguese used their relationship with the Kongolese to advance their own commercial interests. The whole of the Kongo was regarded by the Portuguese as a source of commercial gain, a land destined to supply the Portuguese with raw materials. In addition, the Americas had just been discovered by the Europeans, and newly-established settlements there held greater interest than did African territories. Labor, however, was needed to consolidate and develop the European holdings in the New World.

As the American Indians were unsuited to heavy labor, at an early stage black men from Africa were transported to the Americas. Afonso himself complained about this situation. “Not a day goes by without people being kidnapped to be enslaved,” he wrote to his Portuguese royal namesake, “and neither the nobles nor members of the royal family were spared.”

But the transatlantic slave trade continued to expand. Thus European influence, to which Afonso himself had opened the door wide, eventually brought about the downfall of the Kongo.

While this first attempt at acculturation was a political setback, nevertheless it brought certain benefits. For example, DR Congo’s first written records date from this period. In agriculture several new crops, notably corn (maize) and manioc (cassava), were introduced, subsequently to spread throughout the country.

Commercial activity, furthermore, received considerable impetus, with expansion of overseas trading enterprises as interior merchants took advantage of new coastal economic opportunities.

While the kingdom of Kongo was being ruined by a variety of factors, particularly the burgeoning slave trade, neighboring states attempted to turn the situation to their advantage by expanding their territory and influence. In the 17th century, such states included the Ovimbundu groupings to the south, and the Lunda and Luba empires to the east.

Also located on the southern savanna, the Luba-Lunda cultural complex emerged before 1500.

Archeological evidence suggests the Luba people living between the Lualaba and Sankuru rivers are direct descendents of the Bantu people who once lived at Katoto and Sanga. Luba art, music, poetry, pottery, metalwork, and political structures developed early and, throughout the past millennium, were copied or borrowed by neighboring peoples.

According to Luba legends, their state developed when an eastern hunter, a tall handsome man named Ilunga Kalala, entered their area and defeated the previous weak and uncouth ruler Nkongolo.

Supposedly, Ilunga enlarged the state, established an elaborate court structure, instituted royal etiquette, and founded the ruling dynasty whose power and legitimacy were embodied in bulopwe, a spiritual force transmitted by blood through the paternal line.

While the story of Ilunga Kalala cannot be accepted as literally true, it does reflect a profound social and political transformation as a ruling elite distinguished itself from the ordinary classes of society.

Just when this change took place is not altogether clear although archeological findings at Sanga indicate some class differentiation already by 1000 AD. Presumably, the stories of Nkongolo and Ilunga Kalala developed sometime before 1500.

From the Luba heartland, centralized political structures were transmitted over an extremely wide area of the southern savanna. Sometimes neighboring peoples such as the Kanyok accepted Luba institutions and ideas directly. Even before 1700, minor but ambitious Kanyok chiefs traveled with gifts of tribute to the Luba court, received ritual investiture from the Luba mulopwe (ruler or lord), and returned home claiming superiority over other local chiefs and neighboring peoples who in turn adopted Luba political forms.

The most important carriers of centralized political institutions, however, were the Lunda, living southwest of the Luba. Sometime before 1500-a date confirmed by written evidence from the Atlantic coast the Lunda acquired certain Luba political customs, thus strengthening the ruling family at Musumba, the Lunda capital.

The Lunda ruling family reorganized the court and gained increased magical powers when a Luba hunter Chibind Yirung married the Lunda princess Ruwej. Chi bind Yirung introduced Luba political customs at Musumba and his descendants have since ruled under the title of Mwant Yav.

From Musumba, the Luba-Lunda political forms spread eastwards to the Lake Mweru area where a Lunda general carved out an extensive kingdom, westwards to Angola, where Lunda lords, known by the title Kinguri, conquered local people to establish the Imbangala kingdom of Kasanje, and northwestwards to the Kwilu river area, where Pende people accepted many Lunda political symbols and titles.

While the Lunda disseminated Luba-style political traits, they did not spread other features of the rich Luba cultural heritage. Thus, the many ethnic groups which borrowed, imitated, or were forced to accept Luba-like political centralization, nevertheless retained their own cultural and linguistic diversity.

North of the savanna, in the equatorial forest, lived a culturally homogenous, but politically decentralized people known as the Mongo. The Mongo have lived in the central forest region since before 1000 AD. From Lake Mai Ndombe in the west to the Lomami River in the east, the Mongo shared similar social structures, religious practices, and legends of origin.

Although these people spoke closely similar languages, and traced their heritage to a common mythical ancestor named Mongo, until after 1900 local groups were politically autonomous and unaware of belonging to such an extensive ethnic agglomeration.

Thus, Mongo unity was maintained, not by conscious and extensive political structures, but by frequent contact as the forest people traveled along the many equatorial rivers and streams, and as they exchanged wives.

East of the Mongo, the Lega people settled the area between the Lualaba River and Lake Kivu. Like the Mongo, the Lega were never united under a single ruler. The Lega, however, were linked together through the semi-secret bwami association.

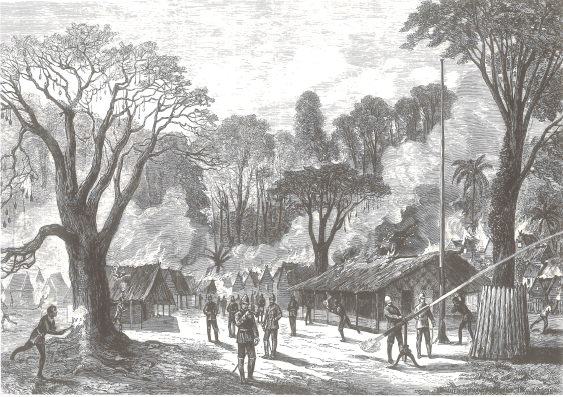

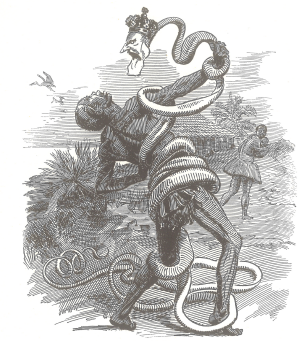

During the second half of the 19th century, Europeans increasingly penetrated what is now the Republic of Zaire. This drawing, made by a British officer, shows the destruction of “Manuel Vacca’s town” by marines of a British expedition led by Commodore Sir William Hewitt, sent against pirates on the Congo (Zaire) River. This illustration was published in the Illustrated London News on November 13, 1875.

Composed of the most respected members of Lega society, the bwami association honored and taught humanistic values such as wisdom, generosity, moderation, dignity, loyalty, and cooperation.

Elaborate initiation systems were designed to carefully inculcate bwami ideas into the men and women privileged to join the association and to advance into its higher ranks. To aid in teaching the initiates and to provide emblems for bwami members, the Lega manufactured a wide variety of carefully crafted art objects including masks, human statues, animal figurines, stools, and knives.

Northeast, in the Uele river region, ethnic groups have a long and rich history of agricultural development. In the forest, the Mangbetu people cultivate palm trees, bananas, and manioc; many cereals such as millet, sorgho (sweet sorghum), corn, eleusine, and sesame; and also numerous vegetables. North, on the savanna, the Zande too are excellent farmers, although they do not grow bananas and palm trees which thrive only in the more humid forest environment.

Actually, both the Mangbetu and the Zande were relative late-comers into the Uele area which earlier had been settled by Bantu speaking agriculturalists. When the Mangbetu and Zande, (the latter being non-Bantu), pushed into the area, they adopted local agricultural techniques and established conquest states governed by a military elite.

ZAIREAN SOCIETY UNDER FOREIGN DOMINATION: THE 18TH TO 20TH CENTURIES

After 1500, Central Africa increasingly came under the influence and domination of outside powers. Introduced progressively by means of commerce, foreign control climaxed in the 19th and 20th centuries as Europeans, Swahili Arabs, and Nubians used armed force to exploit the area. Frequently, they relied on help from African allies who joined with the interlopers to gain power over their neighbors.

The commercial activity of the 18th century extended virtually throughout the whole of what is now Zaire, as the growing demand for raw materials spread inland from the coast.

Slaves, bee’s wax, rubber, and ivory, were exported in exchange for products from the industrial world. These exotic imports reached the heart of the country, not only from the Atlantic coast, as in the 16th century, but also from the Indian Ocean and the Upper Nile.

Commerce grew increasingly important, so that Zaire, which at a certain period of her history had appeared to be a grouping of budding states, was changed into a wide territory with well-defined and flourishing commercial zones. As a result, merchants, rather than warriors and kings, became powerful and prosperous.

The central basin, together with what is now the Equateur region, as well as the sub-region of Mai Ndombe, formed an area which was dominated by the Bobangi people, originally a small fishing group from near Mbandaka.

This complex was linked to the Atlantic coast by Tio middlemen at Malebo Pool who also supplied trade goods for a second network which was, however, territorial rather than riverine. This was the system of caravan routes that linked the interior regions of Bas-Zaire and Kwango with the coast.

Yet another network ran from the coast at Luanda towards Kasai, even extending to the Sankuru River. This network was operated by lmbangala, Ovimbundu, and Cokwe (Chokwe) merchants. In addition, the trade network of the Arabized, or Swahili, merchants extended from the eastern part of the country as far as the Indian Ocean.

It was by these already established routes that European explorers in the 19th century penetrated the interior of the country. Thus, the pre-existing commercial activity facilitated the enterprise by furnishing not only porters, guides, and advisors, but also trade routes.

It was during this period that Leopold II, king of the Belgians, (reigned 1865-1909), took an interest in the country. In 1876 he arranged an international geographic conference, which gathered together the most eminent personalities among those who were interested in the exploration of Africa. At the conclusion of the conference, an “international association for the exploration and civilization of Africa”-known for short as the International African Association (A.I.A.)-was established. The sphere of activity of the new organization was limited to central Africa.

At the same time Henry Morton Stanley (1841- 1904), an American journalist of Welsh origin, was completing his extraordinary transcontinental journey, which lifted the veil which had hidden the course of the Zaire River.

Upon returning to Europe, Stanley attempted, without success, to interest Britain in his discoveries. Only after being rebuffed by the British did he accept the offers of Leopold II and enter the employment of the A.I.A.

Historical Pictures Service, Inc., Chicago

King Leopold II. A picture originally published in the Review of Reviews in June, 1892.

The general assembly of the association then established the Comite d’ Etudes du Haut Congo, or Study Committee for the Upper Congo. This body sent out an expedition, headed by Stanley, into the area.

When Stanley landed in Africa at the mouth of the Zaire River in August 1879, he ascended the river with the intention of establishing trading posts. But Leopold II’s aim of establishing a colony had not yet been achieved.

Thus, while the posts were being established in Africa, and treaties were being concluded with the local chiefs, the committee was dissolved to be replaced by an “International Association of the Congo,” whose objectives were closer to Leopold’s plan. Another step, however, remained to be taken-that of gaining recognition of his enterprise by the great powers of the day.

At the Berlin Conference of 1884-85, summoned at the initiative of Otto von Bismarck (1815-98), chancellor of Germany, this goal was achieved. In the course of the sessions of this important conference, the interests of Leopold II, jealously defended, were safeguarded, and the different states represented at the conference recognized the sovereignty of the International Association of the Congo, as it had become known.

Thus the Congo Free State (Etat Independant du Congo, or E.I.C came into being, as the personal trust of Leopold II of Belgium.

The Congo Free State

The newly-created state lasted a total of 23 years, from 1885 to 1908. Leopold, as ruler of the new state, occupied himself with defining its frontiers establishing its administrative organization. Leopold II, who remained in Belgium, was represented in Africa by an administrator general, resident in Vivi, on the Zaire River opposite Matadi. Then in 1886, the local capital was moved 40 km (25 mi) west to Barna, also situated on the north bank of the river.

By the decree of August 1, 1888, the country was separated into administrative divisions, which were then further subdivided into districts, each headed by a commissioner.

The new state was also equipped with an army, the ”Force Publique,” whose first task was to combat the Arabized elements in the north east where they exercised control over a considerable part of the territory.

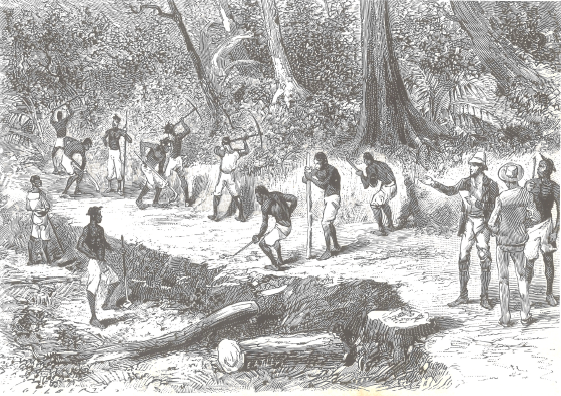

In an effort to promote the exploitation of his territory, Leopold began work on a railroad linking Leopoldville (present-day Kinshasa) with Matadi, near the river’s mouth, to facilitate the transport of goods and raw materials.

At first economic expansion in the new state was satisfactory for the Europeans, although it was often detrimental to the African population. More than 1,800 persons, for example, died in the course of the construction of the railroad.

Before long, however, the Belgian king got into financial difficulties and his activities in the Congo decreased his personal fortune which he had invested in the development of the new state. Besides, from 1902 onwards, an international campaign led by E.D. Morel, an Englishman, was launched against the atrocities being committed in the collection of rubber in the Congo.

As the scandal spread throughout the world, it diminished Leopold’s prestige and forced him to accept an international commission of inquiry which visited the Congo Free State to investigate the allegations of excesses. Finally, on April 20, 1908, authority over the Congo passed from a reluctant Leopold to the Belgian parliament.

Establishing a communications network was one of the preoccupations of the Congo Free State under Leopold’s rule. This picture, published in a German publication in the 19th century, shows road-building in progress. Historical Pictures Service, Inc. Chicago

Historical Pictures Service, Inc., Chicago.

From 1902 onwards, an international outcry arose against the atrocities committed against the African populations of the Congo Free State under Leopold II’s rule. The scandal was particularly associated with the practices used in the collection of quotas of rubber. This cartoon, entitled “In the Rubber Coils. Scene-The Congo ‘Free’ State,” was published in the British weekly, Punch, on November 28, 1906.

The Belgian Congo

The Congo Free State thus became a colony of Belgium, a status it retained until June 30, 1960. The first years of colonization were characterized by a decline in the collection of trade goods and raw materials, the introduction of plantations, and the development of mining industries.

The exigencies of World War I (1914-18) required the intensification of this pattern. After the war, from 1920 onwards, the administration of the colony was restructured.

Several decrees were promulgated which reorganized chiefdoms, sectors, and “native districts.” As a result, large states and ethnic groups were broken down into manageable units, while small and decentralized peoples were joined under chiefs created by the colonizers.

The African populations progressively lost the right to take initiatives on their own, being crushed by the weight of the three facets of colonial power: the administration, the commercial companies, and the missions. Journeys outside one’s region of birth, for example, were rigorously regulated and each individual wishing to travel was required to obtain a travel permit. At times Africans rebelled against the strictures of colonial oppression. For example, in 1931 the

Pende people in Kwilu revolted against high taxes, low wages in the palm oil industry, and administrative interference in traditional political affairs.

With the advent of World War II (1939-45), which Belgium entered in 1940, the burden of colonialism became even heavier as Africans were expected to support Allied efforts with increased productivity, especially in the mining sector.

This situation led to the imposition of severe restrictions by the colonial authorities, provoking revolts in several places. In 1941, a miners’ strike in Elisabethville (now Lubumbashi) was ended by shooting the strikers. In the same way, a revolt of the soldiers of the Force Publique, at Luluabourg (now Kananga) in 1944, brought on violent repression. The colony as a whole, however, prospered, and an apparent calm reigned throughout its vast territories. Thus, the Belgian Congo was judged to be a model African colony.

After World War II, however, a new political consciousness gripped the Congolese “evolues” (i.e. the first generation of African intellectuals). Subsequently they formed themselves into cultural associations which were either regional in character or consisted of interest groups.

These associations included Unelma (Union des anciens eleves des Freres maristes, or Union of Former Students of the Marist Brothers), Assanef (Association d’anciens eleves des Freres des ecoles chretiennes, or Association of Former Students of the Brothers of the Christian Schools), and Abako (Alliance des Bakongo, or the Bakongo Alliance), etc. These associations constituted privileged movements which had the effect of sharpening the nation’s political consciousness.

Other circumstances favored the flowering of new ideas. Internally, the pressures applied by the colonial regime created a spirit of unrest that made itself increasingly felt among the population.

Then, in 1954, Auguste Buisseret, a politician of liberal tendencies, was appointed minister for the colonies. He inaugurated new administrative policies and dissociated himself from the Catholic Church which ran many educational and social programs in the Congo.

The opposition of Catholic missionaries against his policy revealed to the “evolues” for the first time the existence of dissensions between Belgians: Catholics versus liberals, and Flemish versus Walloons.

In 1955, the same year in which Baudouin I, king of the Belgians from 1951, visited the colony for the first time, a Belgian academic named A.J. van Bilsen published the so-called “Thirty Year Plan.” In this plan he proposed that the Congolese populations should be progressively prepared for self-government over the next three decades.

In 1958, the Congolese made great progress in increasing national self-consciousness. On the occasion of the Brussels International Exposition, a great number of Congolese visited Belgium. Coming from different regions of the colony, regions between which movement was most strictly regulated, they were able to meet one another for the first time in the Belgian capital. Some among them took advantage of their visit to become acquainted with the Belgian “Left,” which advocated independence for the Congo.

Also, in the course of 1958, General Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970), who had just gained power in France, came to Africa offering independence to French colonies which wished for it.

On August 24, he visited Brazzaville, capital of what was then the French Congo, (now the People’s Republic of the Congo), on the opposite bank of the Congo River from Leopoldville. Two days after his passage, the governor general of the Belgian Congo, Henri Cornelis, received a petition signed by several Leopoldville intellectuals asking the Belgian authorities to show the same understanding attitude as de Gaulle.

In December of 1958, Patrice Lumumba (q. v.), later to become the first prime minister of an independent Congo, participated in the All-African Peoples Conference, held in Accra, capital of the newly-independent state of Ghana. During his visit he made various contacts with several leaders of Third W arid countries. After his return from Accra, Lumumba’s claims became very precise. “Independence,” he declared on December 28, “is not a present from Belgium, but a fundamental right of the Congolese people,” One week later, on January 4, 1959, serious rioting occurred in Leopoldville, when an Abako meeting was banned. By that time, the move to independence appeared to have become irreversible.

King Baudouin, therefore, in a message broadcast on January 13, 1959, announced that the colony was going to be led towards independence. From this date progress was rapid, perhaps even precipitous. During 1959, Congolese politicians mobilized support for newly formed parties. In January and February 1960, a Round Table Conference assembled Belgian and Congolese leaders, who agreed to establish June 30, 1960 as the date for independence.

TOWARDS A CONTEMPORARY CONGOLESE SOCIETY

The independence that had been so long awaited came at last, and was joyfully celebrated. But, as might have been expected, because of insufficient preparation of the Congolese, a difficult and laborious phase ensued.

After for several months, rumors spread throughout the country, causing disorder. To expedite the withdrawal of the Belgian troops still in the country, the government of Prime Minister Lumumba requested United Nations intervention. United Nations members, wishing to prevent a direct confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union in the Congo, agreed to establish a U.N. force, and in mid-July the first U.N. contingents began to arrive. They were to remain in the country until mid-1964.

Reproduced by permission of the Twentieth Century Fund, Inc., New York

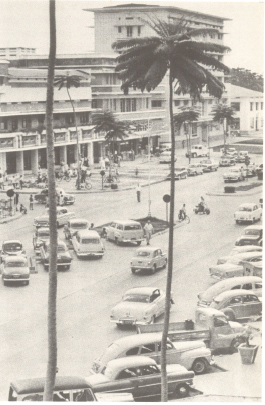

A street scene in Leopoldville-now Kinshasa, the capital of Zaire.

From 1960-65, the political parties, the government, and National Assembly were all put to the test severely, enduring events without being able to control them. Secessions were declared, public figures were removed from the scene, and numerous civil wars broke out in various parts of the country.

Major events during these troubled years included the attempted secession of the province of Katanga (now Shaba), the murder of former Prime Minister Lumumba in January 1961, the 1964 rebellion in Kwilu and in the north and northeastern parts of the country, and the November 1964 attack by Belgian paratroops and European mercenary soldiers on the rebel stronghold of Stanleyville (now Kisangani).

Altogether, during the turbulent period from 1960 to 1965, no less than five different governments were to head the country.

Following a final crisis involving Joseph Kasa-Vubu, president of the Republic, the army high command neutralized the politicians and gave the reins of power to General Mobutu Sese Seko, who thus became president of the Congo in November 1965.

With the wisdom of hard-won experience, he put an end to political agitation. This permitted him to initiate a program of social and economic reform and establish a new and solid foundation for Zairean society.

On the economic level, efforts were directed towards increasing production and formulating a program for national development. This purpose was aided by two external factors: the rise in the price of copper from 1965 onwards, and the financial and technical aid that was granted for the purpose of stimulating the Zairean economy.

This effort was accompanied by a rigorous administrative reform aimed at strengthening the country internally and internationally. One of the first measures was depoliticizing and reorganizing the provincial administrations.

Following a constitutional referendum involving Belgium and political activism from Congolese people, Zaire became the DRC in 1965. The number of provinces was reduced from 22 to 12 in April 1966, and from 12 to 8 in December of the same year. A new constitution was promulgated on June 24, 1967, replacing the so-called Luluabourg Constitution, which had been in force since 1964.

At the same time, through diplomacy, the nation’s leaders tried to create a new image for the country and to demonstrate for the world not only that the Congo was prosperous, but also that the disorders and near-anarchy which had characterized the first years of independence were over.

In order clearly to mark the difference between the two epochs, the government decided to dispense with the country’s old name of “Congo,” and to adopt the name of “Zaire.” This was done on October 27, 1971, a date when the national rebirth was also celebrated by changing the name of the river from Congo to Zaire, by the adoption of a new flag, and by the re-naming of localities and public places.

The movement laid claim to a key idea, publicized by the government with the slogan of the “Return to Authenticity.” People were encouraged to denounce colonialism and repudiate its worst features and so help to establish a “new Zairean society” which would be modern and authentic.

On November 24, 1975, the new regime marked its tenth anniversary, enabling Zaire to evaluate its experience during the previous decade. Thus, after the passage of centuries, Zaire, born as a republic in 1960, in the course of time progressively reaffirmed its national character.

The personalities who find their place in the pages which follow have lived, each in a different manner and under varied circumstances, through a part of the long national evolution that had been outlined above. Together they bear witness to that long development which has led the descendants of the people of ancient Zaire to constitute themselves into a country whose unity is stronger than any type of unity which past regimes had established, and in which its citizens are able to play an important role.

In 1997, President Kabila formally changed the country’s name after overthrowing the previous regime of Mobutu.

In 2006, the DRC held its first multi-party elections in over 40 years, and over 25 million citizens participated. The elections signified the end of a three-year transition period during which time the country moved from intense war to a system of power sharing between the former government, former armed forces, opposition parties, and civil society.

Elections were held again in 2011 when Joseph Kabila was re-elected in a vote disputed by the opposition and deemed flawed by international observers.

The most recent elections were in 2018, when Félix Tshisekedi won the presidency. Though disputed by many, President Tshisekedi’s election was the first peaceful transfer of power in the DRC’s history.