HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

Lesotho is a small, mountainous country located on the Drakensberg escarpment on the eastern edge of the southern African plateau. With a territory of 11,720 square miles, or 30,355 square kilometers, it is completely surrounded by the Republic of South Africa. It is one of the few countries in the world to be encircled by a single neighboring state.

The eastern half of the country rises from 7,800 feet (2,440 meters) to over 10,700 feet (3,350 meters). This region has a heavy average annual rainfall of60 inches (1,905 mm.) and is the source of the headwaters of the Orange River, among others. The mountain area is majestic and rugged, and is mostly accessible only by horse, pony or light aircraft. It is unsuitable for farming.

Topography forces most people to live in the western quarter of the country where it slopes away from the base of the Malo ti mountains to the Caledon River and the plains of the Orange Free State. This area is comparatively level, at between 5,000 and 6,000 feet (1,525 and 1,830 meters) above sea level.

About 70 percent of the nation’s 1.5 million people are crowded into this fertile western strip (about 24 miles or 40 kilometers wide). The overall national density per square mile is about 80 but in this western region the density is about 300 people per square mile. Lesotho has one of the highest rural population densities in Africa.

Overcrowding and overuse have resulted in poor soil conditions and low agricultural yields, forcing many men to work as migrants in South Africa. People seeking less crowded lands have moved further up the mountain slopes to lands traditionally set aside for grazing. The farming of these lands, has added to the problem of soil erosion.

The climate is temperate. Frost occurs in the winter months and hail storms are possible throughout the summer.

The people of Lesotho, the Basotho, are a relatively homogenous people, formed out of Nguni, Tswana, and Sotho speakers in the 19th century. English and Sesotho are the official languages.

EARLY HISTORY

Lesotho is unique among African nations because its people identify themselves with the

nation rather than with any people. This nation-state was created as a result of violent disruptions in southern Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries. During this time white settlers and warring African peoples created a region of refugees. Historians know more about the past of the Nguni peoples (including Zulus) who lived along the Indian Ocean coast than about the history of the Sotho speakers who lived inland. For centuries European traders and missionaries had been active along the coast and many kept records of their observations. Sotho speakers however, had little or no contact with Europeans and they had no written records of their own.

Before the Mfecane or “Upheaval” that upset the entire region in the early 1800s, Sotho-speaking peoples lived along the rivers of what is now the Orange Free State. Of Bantu stock, these Iron Age farmers and cattle herders had pushed down over the centuries from the region once known as Great Zimbabwe, and had spread out along the coast and the fertile lands of the interior.

By the mid 1400s southern Africa had been settled by two large nations of Bantu-speakers: the Nguni groups, which occupied the area around the Indian Ocean, and what are now Swaziland, Natal, and the Cape, and which included Swazi, Zulu, and Xhosa speakers; and the Sotho groups, which occupied areas inland in what are now Natal, the Transvaal, Orange Free State, Lesotho, and Botswana, and which included Tswana speakers and northern and southern Sotho speakers.

During the late 1700s and early 1800s, Sotho speakers were confronted by Afrikaner (Boer) farmers who had settled in the Cape and were pushing northward in search of open lands. Thus, as the whites put pressure on the Sotho in the northern Cape and Orange Free State, the Sotho were forced northward again. Unwilling to adapt to new farming techniques and herding, those people jostled for space in competition with others in the already overcrowded region.

Zulu forces under Shaka exacerbated an already chaotic situation. To escape the devastation during which more than one million people died, the chief of a small Sotho clan, Lepoqo, who later became known as Moshoeshoe (q.v.), led a band of about 2,000 Sotho speakers to safety in the foothills of the Drakensberg mountains, where

they settled on a well-watered plateau, which they called Thaba Bosiu. Moshoeshoe welcomed other displaced peoples and gradually built a nation out of these

assorted refugees. An astute diplomat as well as leader, Moshoeshoe kept Shaka and his successor at bay by paying them tribute and by carefully selecting the time and place of his battles.

In the 1830s, on the heels of Shaka, came the Afrikaners from the Cape Colony. While there was sufficient land, an uneasy peace existed between Bantu and Afrikaner. Eventually, however, the Basotho were unable to protect their lands from the Afrikaners, and Moshoeshoe was compelled to ask Britain for protection. Britain was reluctant to incur the expense, and tried to persuade the Basotho leaders to accept protection from Natal instead. But the Basotho were unwilling to do so, and in 1868 Britain reluctantly agreed to provide protection.

The land shortage that resulted from the Afrikaners taking prime farm land led many Sotho to work as migrants in the South African diamond fields. Some of the money they earned trickled back into Basutoland (as it was then called) and with these funds leaders began buying up rifles wherever they could. In addition to appreciating the advantages of arms, Moshoeshoe also encouraged his people to become proficient horsemen, a skill helpful in warfare as well as cattle rustling.

In 1871, when the Cape Colony became independent, Britain, without consulting Basotho leaders, turned responsibility for Basutoland over to the Cape. The Cape government, however, was unable to administer the territory, and came to blows with the Basotho when it tried to disarm them. The “War of the Guns” of 1880 lasted seven months and cost the Cape government well over 4 million.

By 1881 Britain was forced to intercede and agreed to negotiate a truce. Peace was reestablished in 1883, and Britain again assumed administration for the territory in 1884, when Basutoland became a crown colony. Boundary lines were drawn up and guarantees given that white settlers would never be permitted to hold land. The country then remained under British protection until independence in 1966.

During the 82 years of British rule, Basutoland was administered by a resident commissioner who was under the direction of a British High

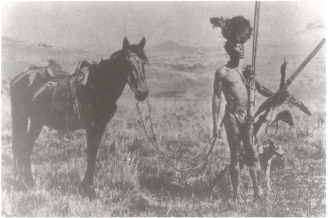

Early 20th century photo of a Sotho soldier.

Commissioner in South Africa. Britain imposed taxes, which obliged the Basotho to work in South African mines to earn the money. In general, Britain showed little interest in the territory, leaving traditional leaders to perform administrative tasks on both local and central government levels. Chiefs collected the taxes, allocated grazing and farming land, and headed the courts in their areas.

The Basotho maintained their own institutions, which helped to keep the nation intact. Through the foresight of Moshoeshoe, French and Wesleyan missionaries had been invited in to teach the people to read and write. In consequence, the Basotho became a literate people, as they are today. Another institution that endured was the tradition of democratic participation in government through a general assembly or pitso at national and local levels. Even the paramount chief submitted proposals to the assembly to win the approval of the leaders of various clans who, in turn, had been selected by their people. In 1903, the national general assembly became known as the Basutoland National Council and it was legally recognized in 1910.

At independence in 1966, the National Council formed the backbone of the new nation. The council had appointed the constitutional commission that drafted the new constitution in 1964 which paved the way for independence two years later. Under the constitution, Paramount Chief Moshoeshoe II became king and a parliament was established.

When Moshoeshoe I died in 1870 he was succeeded by his son Letsie I . There was not a paramount chief of Moshoeshoe’s stature until 1913 when Griffith (q.v.) assumed the chieftaincy. Griffith’s reign was a period of enlightenment in Basotho history: Christianity flourished and spread, a vernacular literature appeared, and medical and educational facilities were developed.

Griffith’s death in 1939 brought about an ugly dispute over the line of succession. Griffith had designated his eldest son, Bereng, to follow him as chief, but the sons of Moshoeshoe, Griffith’s brothers, and other chiefs, favored Seiso. Seiso was made paramount chief, but died within the year. Again Bereng was bypassed in favor of another, his two-year old nephew. A regent was appointed for the interim. Bereng took his protest to the High Court, but the court ruled in favor of the regent. Bereng began dabbling in magic and in 1949 he was executed for complicity in a “medicine” murder.

From differences in the struggle over the succession and, later, from disputes within the Basutoland National Council, several different political parties emerged after World War II. In the council, groups aligned themselves into traditional-conservative and progressive-liberal factions. Leabua Jonathan, a conservative Catholic and staunch supporter of the regent, formed the Basutoland National Party (BNP). Opposed to the regent were many young progressives who favored an early return of the paramount chief-designate from Oxford; they formed the Marema-Tlou party under the leadership of Chief Matete in 1957. Also at this time, in 1952, Mokhekle formed the Basutoland African Congress.

Mokhekle’s Congress party was a prime mover in the drive for independence. In the country’s first election in 1960, the Congress party won a majority of the district council seats. However, in 1965, just before independence, Leabua Jonathan’s BNP won a majority of seats; when the country became independent the following year, Chief Jonathan became the country’s first prime minister.

From the start, the paramount chief, or king, Moshoeshoe II, and Prime Minister Leabua Jonathan clashed over the lines of authority. Moshoeshoe wanted new elections after independence but Jonathan would not risk another election. To safeguard his position the prime minister confined the paramount chief to his palace, deported four of his advisers, and arrested Mokhekle and other opposition political leaders.

In elections in 1970, when it looked as though the BNP might lose the election, the prime minister suspended the constitution, detained opposition leaders, abolished the courts and opposition political parties. The paramount chief was obliged to abdicate, but was permitted to return from exile for a while when he promised to stay out of politics. In 1990, however, the military stripped Moshoeshoe II of his constitutional powers, and he returned into exile in England.

In 1992 however, Moshoeshoe II returned to Lesotho as a regular citizen until 1995 when King Letsie abdicated the throne in favor of his father. In 1996, Moshoeshoe II died in a car accident and was succeeded by his son, King Letsie III.

In August 1994, however, King Letsie III, in collaboration with some members of the military, staged a coup, suspended Parliament, and appointed a ruling council but it was short-lived following domestic and international pressures. The constitutionally elected government was restored within a month.

In 1997, tension within the ruling government caused a split in which Dr. Mokhehle abandoned the BCP and established the Lesotho Congress for Democracy (LCD) followed by two-thirds of the parliament. This move allowed Mokhehle to remain as Prime Minister and leader of a new ruling party while relegating the BCP to opposition status. The remaining members of the BCP refused to accept their new status as the opposition party and ceased attending sessions. Multiparty elections were again held in May 1998.

Throughout the 1990s, politics in Lesotho were deeply affected by economic difficulties relating to the decline of the gold mining industry in South Africa. Low prices for gold on world markets translated into declining employment opportunities for Basotho miners in South Africa, and in turn, declining remittances to Lesotho by Basotho migrant labor.