A HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

Sierra Leone is a small country, roughly circular in shape, and occupying the southwest coast of West Africa between 6° 55′ and 10° N latitude, and 10° 16′ to 13° 8′ W. It is 27,925 sq mi (72,326 sq km) in area, with a coastline extending for 212 mi (339 km) along the Atlantic Ocean. Sierra Leone is bordered on the north and northeast by the Republic of Guinea, while Liberia spans its southeastern boundary.

In relief, Sierra Leone is varied, especially for its small size. Entering the Sierra Leone harbor from outside, the mountainous peninsula would suggest to the observer that the entire country is extremely rugged. But immediately behind the hilly peninsula is a low coastal plain extending for a considerable distance, but rising sharply northeastwards into the Loma Mountains.

The highest peak of these mountains, the Bintumane, is 6,390 ft (1,948 m) in height, being the highest mountain in West Africa west of the Cameroons. The plains are dotted with isolated hills and are strewn with swamps, which are found in shallow valleys and depressions.

Climatically, Sierra Leone falls within the tropical region. There are two seasons-the rainy season from May to October, and the rest of the year, which constitutes the dry season. The rainy season enjoys a mean annual rainfall of more than 80 inches (203 cm), while temperatures of about 80 ° F (27° C) are experienced throughout the year, but rising to about 95° F (45° C) in the dry season.

The latter season also includes the harmattan period December and January-when cold dry winds from the Sahara bring temperatures to as low as 55°F (13° C), especially in the north. There is, however, a high humidity of about 70 percent average throughout the year.

Three main types of vegetation can be distinguished in Sierra Leone. The most typical vegetation of the coast is mangrove swamp, now being extensively cleared for cultivation. Similar clearings have been

made in the once-dense rain forest of the wetter South, though some preservation now occurs in, for example, the Gola forest, in the southeastern hill country near the Liberian frontier. Moving northwards towards drier areas, one encounters savanna grassland, interspersed with farm “bush” country, where much cattle keeping is done.

CONNOTATIONS OF “SIERRA LEONE”

Historically, the term Sierra Leone bears different connotations in the minds of many. The present political boundaries of Sierra Leone, like those of all African countries, are a product of European imperialism.

In the 15th century Sierra Leone was the name given to the mountainous peninsula by the Portuguese who are said to have been the first Europeans to land here.

After the establishment of a British colony in this peninsula in the late 18th century, the name Sierra Leone came to refer to that colony. Up until the late 19th century, the colony was gradually extended by treaties purporting to cede certain adjacent areas and islands to the British. These areas included the Sherbro, parts of Koya country, Bunce, Banana and Tasso Islands, and the estuary of the Rokel River.

The Sierra Leone of today came to include what was referred to in the 19th century as the hinterland, or the interior of the colony. This hinterland spilled over present-day boundaries to include places like Futa Jallon and Melacourieareas where the British continued to exert considerable influence until the 1890s. The boundaries were demarcated by agreements between the governments of Britain, France, and Liberia, beginning in 1895. The present boundaries were finally ratified in 1917.

MIGRATION AND SETTLEMENT

This geographical area of present-day Sierra Leone, before the foundation of the colony, included a number of ethnic groups widely dispersed over its mountains and plains. Among the oldest inhabitants of the coastal area are the Bullom, together with other ethno-linguistically related West Atlantic groups, such as the Gola in the south, the Kissi in the east, the Baga and Nalou in the northeast.

The traditions of the Temne, another early group (though apparently not so long established as the others named), indicate that they came from Futa Jallon, the mountainous region in what is now Guinea, having been driven from there by warlike neighbors. They gradually spread southwards from the Scarcies valley, coming to live beside the coastal Baga.

A reorganization of these coastal groups occurred due to the invasion of a Mantle-speaking people called the Mani, in the middle of the 16th century, which also gave rise to the largest ethnic group in Sierra Leone, the Mende.

The Mani were a Mandinka group emanating from the Mali Empire, whose leader, a queen named Masarico, is said to have been exiled by the Mansa (king) of Mali. Masarico led her followers first southwards, then westwards until they finally made a base in the Cape Mount area of Liberia by the 1540s.

From this area, their armies were sent out to subjugate most parts of the present-day Sierra Leone hinterland, thereby creating sub-kingdoms owing allegiance to the parent one.

Often if the subkingdoms failed to recognize their obligation to the headquarters at Cape Mount, a further invasion was sent against such entities. Thus successive waves of Mani invasions, sometimes 20 years apart, led to further settlement and often the creation of a new ethnic group.

The Temne

Temne traditions speak of Farma Tami (q. v.), who came from the east, as having been the one who first organized them as an important political group. Farma has been identified as a 16th-century Mani king of this area of Temne country.

He brought a number of coastal groups, probably 1as well as fome others, such as the Loko and Limba, together in a loose political structure generally known as the Sapi Confederacy of which he became king. This polity had a formalized structural hierarchy which survived Farma.

When he died, he was buried at Robaga (the name suggesting Temne settlement in Baga countrythe prefix “ro” in Temne meaning “at”). This became the burial place of all kings of Koya who now took the title of Bai Farma-the Temne kingly title of “Bai” being added to Farma’s name.

The Loko

When during his lifetime Farma became too independent of the Cape Mount base, another Mani invasion was sent against him. The effect of the settlement of the Mandinka elements of this invasion on the West Atlantic groups neighboring the Temne is said to have given rise to the Loko. Farma’s invading groups had been assimilated by the Temne.

But the Mandinka element of this second invasion predominated over the West Atlantic to give rise to the Loko group which has a language very similar to Mende. The Loko are still remembered today by the Gbandi of Liberia, a Mande group, as their brothers who went west.

The Sherbro

A southern Bullom group called the Sherbro apparently came to be so called because of a Mani king, Sherabola, who lived on Sherbro Island in the 18th century. The contact with the Man de element gave rise to the Sherbro language, slightly different from that of the Bullom.

The territory was originally referred to as Sherbro to differentiate it from the northern Bullom area, but over time has come to denote the people themselves.

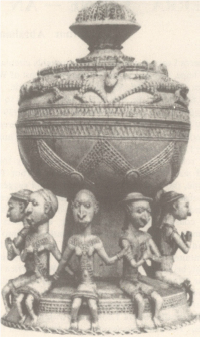

An ivory salt cellar with a lid, which was carved by Bullom craftsmen to Portuguese specifications.

The Mende

The largest ethnic group to emerge from the Mani invasion in the Cape Mount area was the Mende, another product of a mixture of Mani with a West Atlantic Bullom/Gola substratum. It was only in the 18th century that the Mende began moving west of the Sewa River, in south Sierra Leone, in small invading bands.

The first dynamic move of the Mende into the Sierra Leone hinterland proper apparently occurred by the early 19th century. It is identified with the KpaaMende (a subgroup), who pressed the original inhabitants, the Banta, southwards to form the Mendenized state of Bumpe (usually referred to as Banta).

Taken in all, then, the Mani invasions, though they had some deleterious effects on the original people-such as, for example, the disappearance of certain skills, such as ivory carving among the Bullom-gave a more variegated picture to the ethnic scene. They also had some useful social and economic effects by stimulating better metal working and probably cloth weaving.

The Limba

The other streams of migration came into the Sierra Leone hinterland more directly from the north. The Limba are another old group in Sierra Leone having been, it appears, around the Wara Wara hills since at least the 8th century.

They may originally have come from the Futa Jallon mountains which area was indeed a point of dispersal of various ethnic groups towards the Atlantic coast. From the Wara Wara hills, the Limba spread southwards and westwards to occupy areas of Temne and Loko country.

The Soso

The Limba were later affected culturally by other incoming groups. The more northwesterly, which became the Sela Limba and Tonka Limba, were invaded by the Soso (Susu), another Mantle group found in the extreme northwest of Sierra Leone. The Soso identify themselves in their traditions with the 13th-century Soso empire of Sumanguru in the western Sudan.

They claim to have moved towards the Atlantic coast through Futa Jallon after the breakup of Sumanguru’s empire. The Soso, who are found more predominantly in the coastal areas of the Republic of Guinea, settled also among the Temne and this has created a particular Soso strain among the Temne of the present-day Kambia and Port Loko districts.

In fact, the Soso virtually assumed control of the Temne around Port Loko in the 18th century until they were ousted by the Temne in 1816.

The Koranko

Newer Mantle-influenced clans emerged among other Limba sub groups like the Wara Wara and Biriwa. This time they were affected by Mandinka elements from Mali, most likely the Koranko. This latter group, a branch of the Mandinka, (their languages being inter-intelligible), settled by the 15th century east of the Upper Niger, in Sankaran country in the present-day Republic of Guinea.

From there Koranko elements started entering Sierra Leone, the major migration being led by Mansa Morifing of the Mara clan but involving also Koroma and Kagbo Koranko clans.

The major thrust of the Kagbo clan by the early 16th century, led by Mansa Kama, moved deeply into the Sierra Leone hinterland, probably reaching the Atlantic coast. This brought strong Koranko connections with more southerly peoples like the Temne who were spreading eastwards.

In due course, Mansa Kama died and was buried at Rowala in what is today Temne country. The eastern Temne today retained a markedly strong Koranko cultural influence. It was perhaps smaller movements of Koranko clans that gave rise to the Konte, Mara, and Mansaray clans of the Wara Wara and Biriwa Limba.

Yalunka, Kono, and Vai

Towards the extreme northeast, the Yalunka, a Mantle group, fanned out of Futa Jallon to form disparate settlements, later receiving other Mandinka elements by the 17th century and, in conflict with the Fula of Futa Jallon, formed a strong state called Solimana by the late 18th century.

There were other Mantle movements like the Kono/Vai group which is said to have entered the Sierra Leone hinterland from the north before the 15th century. Kono and Vai are mutually intelligible languages, and both groups are said to have originally been a single entity.

In the area of present day Kono country, the group is said to have split up, the one remaining behind being told “Mukon” by the moving group, meaning “wait here.” So the Kono got their name.

The moving group, the Vai, reached the Atlantic coast where the Portuguese met them in the mid-15th century. The Portuguese called their country Gallinas (Gallina meaning hen), because of a preponderance of chicken in what became Vai country.

EUROPEAN CONTACTS: THE FOUNDING OF THE SIERRA LEONE COLONY

While all these developments were taking place in the interior, Europeans were establishing links with the peninsula which eventually culminated in the establishment of the Colony of Sierra Leone in 1787.

Portuguese explorers were stopping at the peninsula as early as the middle of the 15th century and the estuary of the Sierra Leone (Rakel) River quickly became known as a fine natural harbor and a place for obtaining fresh water.

More regular contacts were established through trade, with gold, ivory, and more especially slaves being exchanged by the local inhabitants for European manufactured goods. Between 1482 and 1495, the Portuguese built a fort on the site of modern Freetown where their traders settled. Some Portuguese then went inland and took African wives.

The offspring of such unions came to constitute a privileged group of traders and factors. Attempts were also made by the Portuguese to convert the Africans to Christianity.

Father Balthazar Barreira of the Roman Catholic Jesuit order came to Sierra Leone in 1605. He was well received and allowed to build a church near Kru Bay, in the vicinity of modern Freetown.

His attempts to convert the Soso were, however, a complete failure and he left disappointed in 1610. Subsequent attempts throughout the 17th century similarly met with failure. By the end of the century, regular mission work had been given up completely.

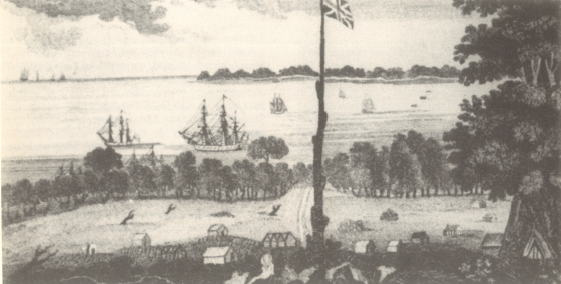

An old print showing the Province of Freedom. The inscription reads: “A view of Sierra Leone River, from St. George’s Hill, where the Free Black settlement was made in the year 1787.”

Trade contacts, chiefly in slaves, continued however, and from the 17th century the British took the lead. They built trading depots (called factories, because they were managed by factors, or commercial agents), which were strongly fortified. Rent was paid to local rulers for these forts or factories.

The English crown granted monopolies to merchants to maximize profits and reduce smuggling. Thus a number of British companies, such as the Royal African Company and the Royal Adventurers of England Trading to Africa, received charters and traded on the Sierra Leone coast with varying degrees of fortune.

Employees of these companies as well as other big English traders married African women, often daughters of rulers or powerful men, and their descendants often claimed and won rights to rule. Thus there came into existence some of the best known coastal families of Sierra Leone today, such as the Caulkers, the Tuckers, the Rogers (Kpakas), and others.

The Founding of the Sierra Leone Colony

But the major impact of British links with the coast was to be the birth of the Sierra Leone Colony. The activities of a few individuals in England, such as the philanthropist Granville Sharp (1735-1813), led to the much talked of Mansfield Judgement of 1772, emphasizing that the state of slavery was not recognized in English law.

This at once released a number of slaves in England who began to constitute a social problem. A group of humanitarians in England, including Sharp and the politician William Wilberforce (1759-1833), formed an anti-slavery movement to try and find a home in Africa for these freed slaves. But to imagine that humanitarianism alone was responsible for creating the conditions that led to the founding of the Colony of Sierra Leone would be a distortion of history.

The greatest slavers in the previous two centuries, the British, were suffering declining economic fortunes in the later 18th century, particularly as competition from the French sugar islands, especially San Domingo (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic), became more severe.

The “West India Interest,” a powerful group based on slave-operated plantations in the West Indies and North America, which was reputed to be able to bring down a government in Whitehall if it decided to vote against it, began to relax its attitude toward slavery and the slave trade.

Absentee landlordism, bad management, soil exhaustion, and many other factors had increased production costs and reduced profits considerably.

Consequently, the price of sugar from Jamaica, the British sugar island, rose proportionately. The French islands, on the other hand, were producing cheaper sugar, and an inchoate industrial Britain preferred to buy its food at the cheapest price.

The West India Interest did not oppose the proposals of the humanitarians to repatriate the ex-slaves, although they consistently voted against the British abolition of the slave trade.

On the suggestion of Dr. Henry Smeathman (17?-1786), a botanist who had visited Sierra Leone, the British government selected the Sierra Leone Peninsula. Thus in 1787 the first batch was repatriated, together with some white women, and settled on a piece of land obtained from the Temne rulers of the peninsula.

This was initially not a British colony. It was a self-governing entity called the Province of Freedom equipped with an idealistic constitution drafted by Granville Sharp and with a government run by the settlers themselves. But this first settlement failed and was abandoned in 1789 largely because of the hostile environment and hostile neighbors.

Sharp persisted in his efforts to rehabilitate these former slave. Consequently, shortly afterwards the Sierra Leon Company was chartered to finance the settlement, under the direction of a banker, Henry Thornton

A number of slaves who had been freed in Nova Sco9 as a reward for their loyalty to the British during the American War of Independence (1776-83), were now transported to Sierra Leone to join some of the original settlers. The company took over the administration of the settlement and in 1792 appointed Lt. John Clarkson as the first governor.

In 1800, another group known as the Maroons, from Jamaica, joined the two other groups, thus swelling the population. In origin, the Maroons were mostly from Asante (Ashanti) in what is now Ghana.

In Jamaica, they had escaped into the mountains, become marooned there, and had then constantly harassed the Jamaican administration. They arrived in Sierra Leone at a particularly auspicious moment for the company which was faced with a rebellion of Nova Scotians arising from accumulated grievances over land allotments, quit-rents, and other matters. The Maroons readily assisted the company to suppress the revolt.

In 1808, the British government took over the settlement as a Crown Colony. Almost from the beginning, the company had been in financial straits, as most attempts to increase revenue, for example by growing cash crops, had failed. Its request to the British government to take over the administration was accepted because, with the abolition of the slave trade imminent, the British needed a West African naval base.

This base was to become the home port of the naval squadrons assigned to arrest slave ships, as well as the seat of an Admiralty court to try the slavers who were caught. When the Abolition Bill was being passed in the British Parliament in 1807, the West India Interest, whose profit had been reduced to zero, voted in favor.

The Admiralty Court in Sierra Leone was transformed into a Court of Mixed Commission when Britain got other nations similarly to proscribe the slave trade. In this way the court was able to try all nationals whose countries had anti-slave-trade treaties with Britain.

The village of Bathurst in the mountains south of Freetown in the earlier 19th century. Named for the 3rd Earl of Bathurst (British secretary of state for war and the colonies from 1812-27, who was intimately involved in the abolition of the slave trade), Bathurst gave its name to the neighboring village of Leopold, with which it was amalgamated in 1825.

The Recaptives

The British squadron patrolled the whole West African coast, and brought offending ships to Freetown, as the capital of Sierra Leone had been named in 1792. In Freetown, after adjudication, the captives were set free.

These people-first captured and enslaved, then recaptured on the high seas and subsequently freed-were known as Recaptives or Liberated Africans. They added a new element in the population to that of the original westernized settlers.

Many of the Recaptives were of Yoruba origin. But there were others from the Congo and elsewhere, and even some Kissi Recaptives from Sierra Leone itself. These were settled in places surrounding the colony which often bore the names of their areas of origin.

Eventually thousands of Recaptives more than 40,000 by 1850-swelled the colony’s population. Many villages were founded, where Recaptives usually practiced their original modes of living.

Largely through thrift and industry, many of the Recaptives broke into the snobbish and hitherto exclusive domain of the settlers of Freetown. They became wealthy through trade, bought property in Freetown, intermarried with the settlers, became Christians and assumed some western habits.

By the second half of the 19th century, this breaking into the preserve of the settlers had ushered in a fusion of the two groups Recaptives and Settlers-to give rise to the Krios (Creoles). Krio culture became a fusion of the indigenous customs of the Recaptives mainly

Yoruba-and westernized habits of the settlers, coupled with missionary and Victorian values brought in through the colonial experience.

DEVELOPMENTS IN THE INTERIOR: THE 18th AND 19th CENTURIES

Meanwhile developments in the interior were leading towards the consolidation of some relatively extensive polities as well as intricate commercial networks.

This was to have considerable implications for relations between the hinterland and the Sierra Leone Colony, and indeed was later to result in the establishment of colonial rule over the rest of what is today Sierra Leone.

Political Organization

The creation of the Yalunka state of Solimana in the late 18th century has already been mentioned. The state was centered around the capital, Falaba.

The manga (ruler) ruled the state and initially also the capital, aided by an assembly of elders. Various Yalunka khoris (countries) which constituted the state, were ruled in all internal matters by their own tamangana (town rulers).

Various rights of appeal, interkhori relations, declarations of war and similar questions, were, however, subject to the authority of the ruler. Large areas of Koranko country were also part of Solimana, but only insofar as Solimana could exercise a dominant influence and obtain regular tribute. The state of Solimana lasted until 1884, when it was destroyed by the forces of the Mandinka warrior, Samori Toure.

Many precolonial states of varying sizes in the Sierra Leone hinterland were organized along similar lines. Another strong and extensive state ruled by Almamy Suluku, existed among the Limba of Biriwa in the second half of the 19th century.

By the mid-19th century the Koranko had relatively smaller polities, but these were linked in a kind of psycho-political chain with Morifindugu, which had apparently been their point of dispersal into the Sierra Leone hinterland.

Though the ruler of Morifinduguwho, in the second half of the 19th century was Marlay Bokari (q. v.)-did not rule these other Koranko states, the latter often resorted to Morifindugu in times of difficulty.

By the later 19th century, state organization among the Mende followed one or the other of two patterns. One type was based on the personality of the ruler, and included such states as those under Kai Londo of Luawa, Nyagua of Panguma, Mendegla of Joru, and Makavoray of Tikonko.

These tended to be amorphous, and territory could be added to or taken away from them depending on the forcefulness of the king.

One of the few remaining examples of the thatched cottages built in Freetown by the early settlers.

The other type had relatively fixed territorial limits and existed as it was despite the activities of the ruler, who was more or less a primus inter pares (“first among equals”).

Rulers in the latter type of state-a category which included Sherbro, Gallinas, Bumpe, and Kpaa-Mende did not assume the dominant position held by rulers in the amorphous states.

In all states, however, walled towns with open fakais (farm settlements) were grouped into countries, and a number of these later constituted the state. The Sherbro was a strong state in the 18th century, ruled by the Bai Sherbro (king), who lived on the Sherbro Island.

But by the close of the 19th century it had become a Mendenized and declining polity whose provincial rulers were virtually independent of the Bai, although they still paid homage to him.

Succession to high office was basically similar in both types of state, though slight variations existed. It was generally based on a demonstration of some outstanding quality, usually leadership in war, but a successful moriman (charm-maker priest) could become a ruler.

Among the Mende this did not mean that rulers came from a ”ruling family,” except that members of certain families had more opportunities to demonstrate the necessary prowess.

In some other areas, in the territories of the Koranko and Limba, candidates for high office had to demonstrate such qualities, but usually also had to belong to a ruling family.

Internal Commercial Organization and Interior Wars

Many of these polities were linked with each other by commercial needs. Internal modes of exchange involved the use of commodities produced locally as well as from distant states or towns. Labor was exchanged for goods, as was expertise.

Goods traveled long distances over the trade routes of the interior. Here, where a route runs over a river, it was spanned by a hammock bridge.

Traveling Yalunka blacksmiths visited Koranko country on contract. Later, Koranko smiths made similar visits to Mende country. Manufactured goods, such as country cloth, soap, or hoes, were traded extensively.

Certain goods were traded over long distances, passing through a number of states. These included gold, cattle, and cotton. Gold was traded from Boure in the upper Niger to various areas of the Sierra Leone hinterland.

Cotton from Sankaran, now across the frontier in central Guinea, found its way to Limba country where it was exchanged for cattle from Futa Jallon. Kono cloth was valued as far away as the state of Biriwa Limba, ruled by Almamy Suluku, while Sankaran cloth was famed in distant Freetown.

International markets to handle the trade also developed in the interior. In the 19th century, there were, for instance, such markets at Katimbo in Biriwa Limba, at Koindu in Kissi country, at Falaba in Solimana, and at other places. Indigenous currency systems emerged as well, for example in the Kissi/Mende areas.

Wars in the interior did not often affect this trade, despite the strong belief to the contrary of the colonial administration in Sierra Leone. Centers of strong political authority became areas of protection for trade routes.

Wars were sometimes fought, as among the Temne in the late 18th and 19th centuries, for the control of important trading areas such as the headwaters of navigable rivers. Sometimes rulers in the interior, such as Sattan Lahai (q. v.) in Kambia, on the Great Scarcies River in the northwest, deliberately blocked trade routes for political reasons.

But this did not always stop the trade, nor, often, did political wars. Stoppages were often temporary, and alternative routes were quickly developed in areas where a continuous stoppage occurred.

In 1877, for instance, the Limba of Yagala destroyed the way station at Kabala on the important Falaba-BumbanPort Loko trade route. The ruler of Kabala, Boltamba, quickly teamed up with Suluku of Biriwa Limba to found another route. What often created the alarm was that those at one end of a particular route, for example the Krio traders at Kambia, who were affected by Sattan Lahai’s activities, made a major issue of the matter.

The economic difficulties of the 1870s and 1880s were quickly blamed on the interior_ wars, and not on the world trade depression which prevailed at that time. In fact, the volume of exported produce increased in these periods, although the value declined. In 1875, a war waged by Mende professional warriors spilled over into “British Sherbro.”

Governor Sir Samuel Rowe (term of office 1885-88) determined to teach the Mende a lesson for violating “British territory.” He led an expedition to the Bagru region in Sher bro country, entered into an agreement with the Mende never to hire out warriors, and fined them 10,000 bushels of rice (because, he said, “the country is one immense rice farm”).

Relations with the Interior

It was primarily the trade from the interior that led to the development of relations between the Colony and the hinterland beyond it. By the early 19th century, it had become evident to the colonial administration in Sierra Leone, as well as to its inhabitants, the trade with the interior was the key factor in the colony’s economy.

The authorities therefore began to promote this trade. In Freetown, a newspaper, The Royal Gazette and Sierra Leone Advertiser, was founded in 1808, and gave much of its space to reporting situations in the interior, which were felt to affect trade.

It also paid attention to areas where gold and other commodities were plentiful. Traders coming from the far interior were well treated by the authorities, and their visits widely publicized.

The administration also tried hard to promote good relations with rulers in the interior. Expeditions, or missions, headed by Europeans, were successively sent inland primarily to discover commercial possibilities and to meet the rulers from those areas from which much of the trade came.

In 1822 the Scottish explorer, Gordon Laing (1793-1826) went as far as Falaba; Cooper Thompson (?-1843), a Church Missionary Society linguist, went to Timbo, the capital of Futa Jallon, in 1841.

Winwood Reade (1838-75), traveller and author, reached Boure, on the headwaters of the Niger in what is now Mali, in 1870; William Budge was sent to the Kpaa-Mende in 1879. Numerous other missions headed by Africans were also sent, like those of the educationist Edward Blyden (1832-1912) to Falaba (1872) and to Timbo (1873).

Apart from missions to the interior, the interests of the Sierra Leone authorities consistently accompanied those of its subjects (as the Africans in Sierra Leone were regarded) into the hinterland.

By the mid-19th century, many Krio traders from Freetown had settled on the headwaters of rivers at the farthest navigable points-such as Port Loko, on the Port Loko Creek, Kambia, on the Great Scarcies River, Mofwe, on the Bum River, and Senehun, on the Bumpe River, which thus became centers of small Krio trading communities.

Here much of the trade in gold, ivory, hides, palm kernels, and other products, was handled before being sent to Freetown or Bonthe for shipment to Europe. In Kambia, by the 1880s, the Krio traders had elected themselves a ”king of the Creoles” in the person of an influential trader, Thomas Johnson.

View of a street in Freetown, as it appeared in about the 1860s.

The direct involvement of the British from Sierra Leone in these inland areas was motivated partly by a wish to protect British subjects, but more by the desire to mediate in or forcibly put down any conflict between the local inhabitants which was felt to be inimical to trade.

The Krios habitually capitalized on this, and reported the least disturbance which affected them, often in the form of lengthy memoranda to Freetown or to metropolitan chambers of commerce, of which many Krios were members. The disturbances at Kambia in the 1850s between Bilali of Tonka Limba and the Soso alliance, spearheaded by Sattan Lahai, and the so-called Yoni disturbances of 1887-88, are cases in point.

British involvement often led to the signing of treaties with the local rulers and the exchange of presents. Treaties, for instance, were signed with the rulers of the Sherbro, with those of Morea country (around the Melacourie River in what is now Guinea), with the Temne, who had ruled Port Loko since 1836, and with Futa Jallon in 1873.

Most of these early treaties, that is those before the 1880s, were meant to prevent the local rulers making wars which were thought to affect trade adversely. British subjects who had settled in the territories of these rulers were to be protected.

Sometimes by these treaties the British government, as represented in Sierra Leone, was given the right to adjudicate in disputes between indigenous rulers. Territories in which the British had such treaties were often described as being under British ‘infuence.’

By the later 19th century, a department had been set up in Freetown to handle relations with the interior. Initially, it was a one-man department under T.G. Lawson who was appointed “Native Interpreter and Government Messenger” in 1852.

Lawson took charge of the traders coming from the hinterland and reported to the Colonial Secretary all information received about developments in the interior. He also accompanied expeditions to the interior to sign treaties or settle disturbances. In 1888, after Lawson retired, the department, reconstituted first into the Aborigines

Fourah Bay College in earlier days.

Department, then as the Department of Native Affairs in 1891, was headed by J.C.E. Parkes who had been working with Lawson. Overland messengers, and an Arabic writer and his assistant, were all incorporated in the enlarged department.

POLITICAL AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE COLONY

The Krios, who were directly or indirectly involved in these maneuvers by the Administration, were becoming more vocal as the century wore on. They were becoming increasingly educated and affluent, and were increasingly able to participate in the business of the Sierra Leone establishment.

In 1848 the Church Missionary Society (C.M.S.) Grammar School was opened, and its counterpart for girls (later to be renamed the Annie Walsh Memorial School), in 1849.

Krios, a few sons of chiefs in the interior, and Africans from other parts of British West Africa, increasingly gained secondary and, later, college education in Freetown.

Earlier, the C.M.S. had set up an institution to train local teachers and missionaries at Fourah Bay in 1827. As the years went by, this college was enlarged in scope and began to offer degrees after becoming affiliated to the University of Durham in England in 1876.

The more affluent, however, sent their children to Britain, often to pursue courses that were not available at Fourah Bay, such as medicine and law.

Thus many young Krio doctors, lawyers, and clergymen became eminent not only in Sierra Leone society but along the West African coast as well. The first African to become a bishop was Adjai Crowther (1809-91), the first student of Fourah Bay. T

he first two Krio doctors-Africanus Horton and William Broughton Davies qualified in 1859. The first African to be knighted in England was the distinguished Krio barrister, Sir Samuel Lewis.

Thus, prospering in trade and obtaining education, the Krios became more and more articulate, making their views heard in petitions, in addresses, and in their own newspapers, such as the New Era in the 1830s, as well as in the Sierra Leone Times. But they had no control over policy under Crown Colony rule.

Before the 1860s, the Colony was ruled by the “Governor in Council”-the Council in effect being comprised largely of senior European officials, such as the Chief

Justice, the Officer Commanding the Troops, and the Colonial Secretary. Laws for the Colony were made by this body, but the governor could if he so decided ignore his council and override its decisions.

In 1863 the British government granted a new constitution to the Colony, due in part to press agitation, particularly that of the New Era. The Governor’s Council was abolished and in its place an Executive Council and a Legislative Council were established.

The former was virtually a replica of the old Governor’s Council. The Legislative Council had provision for only two unofficial members, who were appointed by the governor. Initially, the only Krio representative appointed by the governor was Charles. Heddie.

The governor then asked the business community to elect one representative. John Ezzidio, an African, defeated John Levi, a European. The Secretary of State for the Colonies then advised the governor that the post was meant to be filled by his appointee, and that in the future he should appoint a representative, and not have him elected.

The elective principle thus disappeared for the next six decades. Though the Legislative Council made laws, these had to be ratified in Britain and could be set aside if the British so desired. Thus the Krios were politically powerless in the Colony. They were furthermore to lose what economic and social power they had as the 19th century ended.

Fourah Bay College at Mount Aureol, as it appeared in the 1970s.

For the British, due to the prevailing doctrine of Social Dar,winism (a popular theory of that age, which held that life was a struggle for existence in which the fittest survived), changed their former policy of encouraging Africans to take over administration.

In consequence, Africans were no longer appointed to important positions. No African doctor, for example, was allowed to be senior to a European counterpart, even if he was more qualified.

With the advent of big European firms and, later, of Lebanese businessmen, to whom concessions were granted, the Krios found themselves unable to compete, and their economic strength declined.

THE SAMORIAN ERA

Developments in the north of Sierra Leone were to coincide with the era of European imperial expansion and would contribute to the establishment of a protectorate by the British over the rest of Sierra Leone in 1896.

By the 1870s, Samori Toure (1830-1900), a great Mandinka warrior and leader, was establishing an empire around Konya country, in what is now the Republic of Guinea. Samori received the bulk of his arms supply from Sierra Leone through long distance trade across the hinterland.

By 1822, he had decided to bring certain areas of this hinterland under his hegemony so as to have control of the trade routes. He therefore sent one of his generals, ‘Nfa Ali, to subdue these areas.

The attack on what is today the Sierra Leone hinterland began early in 1884. By September the Yalunka state of Solimana had been destroyed by the Sofa, Samori’s warriors. Limba country, including Almamy Suluku’s state of Biriwa Limba, was subdued before the year was out. Also conquered were large sections of Koranko country.

The governor of Sierra Leone wrote a letter to Samori during the siege of Falaba, the capital of Solimana, indicating that “Falaba and the countries below it, (meaning the Sierra Leone hinterland), are on friendly terms with this (Sierra Leone) government,” and that it would be unfortunate if Samori took Falaba. But this did not deter the Sofa.

Samori, however, wanting to please Sierra Leone, the source of his arms, promised the governor that he would rebuild Falaba. He kept his promise, and similar sentiments made it possible for a British officer, Major Morton Festing, to succeed in ridding Suluku’s state of Biriwa Limba of the Sofa forces of occupation in 1888.

But by 1890, a revolt in Samori’s empire led him to send his Sofa out again to reconquer large sections of the Sierra Leone hinterland. One of his lieutenants, Foday Benia Porekere, attacked the eastern portions of the Sierra Leone hinterland in 1893. After assisting rebellious groups in the state of Kai Londo

The Sofa, warriors of Samori Toure, the great Mandinka warrior leader, posed a challenge to the European powers in the later years of the 19th century. This picture shows a mounted Sofa warrior.

, Porekere moved to Kono where Kai Londo reestablished his authority. He took a number of towns belonging to Nyagua, and then threatened to overrun Konike Temne (in central Sierra Leone, near the headwaters of the Taia, known in Sherbro country as the Jong River) so as to control an alternative route to Freetown.

Nyagua, in treaty relations with the British, reported the attack on his territory. Porekere was warned by the British administration to desist from his threatened attack on Konike. Meantime, the French were attacking him from the rear while the British joined Nyagua to attack him from the front.

As a result of misinformation, the British and French ended up fighting each other, each party thinking the other to be the Sofa. Both commanders were killed. Then Porekere advanced to Bagbema on the Sewa River, ready to pounce on Tungea, near Panguma.

There he was attacked by the British force and killed by a chance shot. Thus the Sofa threat was warded off.

THE PRELUDE TO THE COLONIAL OCCUPATION

By this time, however, British interest in the hinterland had developed beyond that in trade alone. This was the period usually described as the “Scramble for Africa.” Britain did not want to be over-reached by the other European power in this area, France.

The French had been active from their base in Senegal and had signed a few treaties in the area of the Northern Rivers-i.e. the Melacourie, Bereira, Rio Pongas, and Rio Nunez, all in what is now the Republic of Guinea.

Unlike the British treaties, some of the French agreements were claimed to be treaties of “suzerainty and protection.” British and French interests in this area of the northern Sierra Leone hinterland were thus bound to come into conflict.

The two powers therefore consulted in 1882, and drew up a convention to impose a boundary between the Scarcies and Melacourie rivers, demarcating their areas of interest. This was the beginning of a series of boundary delimitation agreements between European powers which were to determine the present boundaries of African states.

Though the French depended on treaties signed with the indigenous rulers as a basis for claims to territory, a great portion of the hinterland was claimed by them “by right of conquest.” The French had driven the Sofa out of this area, so they claimed that it had become theirs. If the French could have occupied all

Disturbances were frequent in the interior in the final years of the 19th century. This picture shows a Mende warfence, built to discourage attack.

the areas they claimed, the Sierra Leone hinterland would have been lost to the British, and the Colony itself would have been hemmed in, thus losing its trade, profits, and revenue.

The British therefore proceeded to sign more treaties on which they relied to counter French influence. They had begun to fear that local rulers would cede their territories to France, and therefore in 1888 produced a “standard treaty” containing a special clause that no ruler was to cede his territory to any other foreign power “except through and with the consent of the Government of Her Majesty.”

This clause made its first appearance in a temporary treaty signed by Major Festing with Almamy Suluku of Biriwa Limba in February 1888.

Two British commissioners were appointed in 1889 to tour the hinterland and sign these treaties. G.H. Garrett was to sign treaties in the north while T.J. Alldridge was to do so in the south. There was no protectorate or protection clause in these treaties.

In 1890 the Sierra Leone Frontier Police Force was inaugurated. Its duties were supposed to be only those of a “frontier Force.” These included guarding the frontier road which Governor Sir James Hay (term of office 1888-91) had encouraged local rulers to construct. This road ran parallel to the coast, from Kambia in the northwest to Sulima in the south, approximately marking the boundary between the colony and its hinterland. Its construction was intended to stop the passage of large slave caravans, prevent local wars, and protect British subjects, such as Krio traders. But before long the force won notoriety for petty tyranny.

An avalanche of complaints kept bombarding the governor’s office, drawing attention to a paradoxical situation in which the ostensible protectors of the people had become their oppressors. Although not supposed to interfere with local customs, members of the force meddled frivolously in local affairs.

They maltreated and disrespected kings and chiefs in the presence of their subjects. Even Governor Sir Frederic Cardew (term of office 1894-1900), who was often prone to side with them, admitted their brutalizations and misconduct, dismissing a number of them in 1895.

Apart from the restrictive clause about cession of territory, these ‘standard treaties’ were still treaties of peace, amity, and commerce. Many of the local rulers regarded these treaties as allying them with the British. Especially in the north, where the Sofa presence was still imminent, the rulers were looking for allies against the Sofa enemy.

In fact, when the French were engaged in fighting the Sofa while the British appeared cool about participating in the struggle, some rulers, such as Bambafara of Nieni, told British emissaries that they would move their allegiance to the French if the British would not help them.

In 1890, Garrett reported to the governor that many rulers of Sankaran, Solimana, and Koranko countries had signed treaties offering their countries to the British “on condition they be protected against the Sofas.”

The ruler of Kaliere in the former Solimana state had signed a treaty with the British in 1890. When his son, Isa, succeeded him in the same year, he fell out with the Sofa, whom he had been supporting. The British refused to help him when the Sofa attacked his town, so he returned the treaty and went to the French with presents to seek help.

THE PROTECTORATE AND THE NATIONAL LIBERATION STRUGGLE

But the pace of imperial expansion moved quicker. Soon any attempts to parley with the indigenous rulers were abandoned. The original agreements between the European powers on the one hand, and treaties with the local rulers, concluded during the 1880s and early 1890s, on the other, were likewise now abandoned. The British had fraudulently claimed these treaties of friendship to be treaties of protection.

But by the mid-1890s, the British no longer bothered to sign treaties with distant areas with which by then they had become familiar. In January 1895, Britain and France signed a new agreement delimiting their spheres of influence.

When local rulers in the north questioned the British as to which side they were to consider themselves to belong, the governor urged them “to await patiently the settlement of the boundary question.” Their views no longer counted.

The Anglo-French agreement of 1895 fixed the eastern boundary at 14° W longitude. This made Sierra Leone’s eastern boundary a straight line which cut Kai Londo’s state into two, with one half, including the capital, Kailahun, in Liberian territory. Despite appeals from the governor to ease the hardship consequently imposed on Kai Londo’s successor, Fa Bundeh, the Colonial Office paid little attention to the matter.

The Liberian government sent a customs official to Kailahun in 1907, but he was ejected soon after. In 1911, an agreement was made granting the “Kailahun Salient” to Sierra Leone in return for a slice of Gola territory to the south. This agreement was finally ratified in 1917, giving Sierra Leone its present boundaries.

The boundary demarcation was therefore a matter of convenience only to the European colonial states, which ignored African interests. Limba traditions claim that the boundary ran through one Limba house in Wara Wara country; the front verandah formed part of French Guinea, while the back room was in Sierra Leone!

When Governor Cardew took charge of the Colony in 1894, he lost no time in requesting the Colonial Office to approve his plans for the declaration of a protectorate over the British sphere of influence. He made two tours into the hinterland in 1894 and 1895 to promote his protectorate idea and to familiarize himself with the area.

Apparently, he made little mention of his proposed house tax which was expected to pay for the protectorate administration. In 1896, the Protectorate Ordinance was passed although its provisions were not properly explained to the people.

The Protectorate was divided into five administrative divisions-the Karene, Ronietta, Bandajuma, Panguma, and Koinadugu districts. Each of these was under the control of a district commissioner.

A new hierarchy of courts was constituted, and many legal matters, which the local rulers had previously settled, were removed from their jurisdiction. These measures were introduced at a time when the rulers were still recovering from their vexations with the Frontier Police.

To further complicate matters, the British imposed a house tax, which was rightly interpreted in customary law to mean that the people did not own their houses and the rulers did not own the country.

Lengthy petitions were written and several delegations were sent to the governor to state a host of grievances. In every instance the house tax in particular was abhorred.

The governor dismissed these petitions, and informed the rulers that two districts Panguma in the east and Koinadugu in the northeast-because of their distance from European contacts were not to pay tax in the first instance. The remaining three were to pay beginning in 1898.

Governor Cardew appointed Frontier Police officers to act as district commissioners and to begin collecting the tax promptly. The collectors, however, encountered a general reluctance to pay.

The Frontier Police therefore used methods that were to provide the spark necessary to light the powder keg of revolution. When Captain Wilfred S. Sharpe, the district commissioner of Karene, northeast of Port Loko, attempted to collect the tax by force, deposing chiefs and sentencing those who would not pay, he made the fatal mistake of firing at people supposed to be supporters of Bai Bureh, the ruler of Kasse, north of Port Loko, who was believed to be the brain behind the resistance.

The so-called Hut Tax War had begun. Bai Bureh’s almost legendary fame spread far beyond the imaginable confines of the areas immediately under his influence. He thus became the center of the so-called Temne resistance.

While British troops were engaged in fighting Bai Bureh in the north, in April 1898 there occurred a sudden, spontaneous, and unexpected outburst of resistance in the Mende areas to the south, directed against all European or colonial establishments or persons.

Missionaries, traders, colonial officials, and others, were plundered and massacred. Thomas Neale Caulker (q. v.), chief of Shenge, a small port on the coast opposite the Plantain Islands, who asked his people to pay, was murdered by his own family.

Madam Yoko (q. v.), and Nancy Tucker, who promised to pay, barely escaped with their lives. Few escaped. Because of the nature of this revolt, it petered out before long, there being no clear leader. But Bai Bureh conducted a highly-organized guerrilla war which engaged British troops for ten months.

After the rainy season, the British, with the aid of a few African collaborators, formed ‘flying columns’ and took the offensive, shelling ruthlessly, and destroying crops ready for harvest.

The supposed ringleaders, Bai Bureh, Nyagua, and Bai (Beh) Sherbro, were arrested. A commission of enquiry was set up. But, there being no evidence against them to warrant a conviction, the three were exiled to the Gold Coast in July, 1899. Many other people were tried for murder in the Mende areas, however, and were hanged.

THE ESTABLISHMENT OF COLONIAL RULE

After the resistance of 1898, the British became more concerned about consolidating their rule. Until the end of World War I, the large pre-colonial states in what is now Sierra Leone were broken up, and subordinate rulers, styled paramount chiefs, accepted on the same footing as their former overlords or kings. Chiefdoms replaced states, and their number increased with bewildering rapidity, reaching a total of 217 by 1924.

Moreover, after those who had fought the British had been exiled or hanged, puppets, including women, were put forward and also recognized as paramount chiefs.

The source of legitimacy to traditional authority was transferred to the British administration. Any paramount chief whose conduct was supposed to be detrimental to British interests was promptly deposed. The British were now in full control, and the people settled down to a helpless acceptance of alien rule.

SOCIO-ECONOMIC TRENDS

The first few decades of colonial rule were characterized by a colonial preoccupation with law and order. No proposals likely to disturb the pax Britannica by uprooting people from their natural avocations were approved. Until the 1930s, it was a period of colonial consolidation.

In 1906, a school was opened at Bo, 177 km (110mi) east-southeast of Freetown, for the “sons and nominees of chiefs.” The main purpose was to familiarize the pupils with European ways without alienating them from their traditional culture.

They were expected to become model colonial chiefs. Emphasis was put on the dignity of labor. None of the graduates was to be employed in any official establishment. By 1916, however, several factors had combined to make this policy unrealistic.

A negligible number had succeeded to paramount chiefships, but those who did were far from model chiefs. In addition, the presence of educated elements in chiefdoms that were excluded from the corridors of power was thought to be dangerous to peace and order.

Consequently, Bo School graduates began to be employed in the lower rungs of the colonial service as agricultural instructors, surveyors, and clerks.

As early as 1894, Governor Cardew, impressed by the quantity of the natural produce of the country, had proposed a railway running eastwards across the country, into the hinterland. Its construction began in 1896.

By 1906 it had reached Balima, where it marked time for two years before reaching what was to be its terminus, Pendembu, 463 km (227 mi) away

The building of a government railway, running eastwards across the country, stimulated the export of palm products, but did not achieve other hoped-for results. This picture shows Bauya Junction in 1925.

from Freetown, in 1908. A branch line, completed in 1915, was also constructed from Bauya, 80 km (50 mi) east-southeast of Freetown, to Makeni in the northern province.

Before the mining boom of the 1930s, the railway represented the only capital investment project in Sierra Leone. Not oriented towards production, it was intended to serve a pre-existing extractive industry, which produced palm oil and kernels.

No new varieties were introduced, no large-scale plantations were undertaken, and above all no new technologies were encouraged. In the event, the export of palm products doubled within a few years of the building of the railway, but failed to have a magic-wand effect upon the Sierra Leonean economy. The railway itself was declared a liability in the 1940s, and was eventually phased out in the late 1960s.

About the turn of the century, Levantines, incorrectly described as Syrians but in actuality Lebanese, began to arrive in Sierra Leone. With little or no money, they seized every opportunity to trade and make profits as the recaptives had done before them.

They did not fear or hesitate to move to remote hinterland areas and to open shops there, advancing goods to the local inhabitants in return for produce, after they themselves had obtained the goods from large European firms operating in the country.

Before long, many had become fairly prosperous but earned the displeasure of local middlemen, whom they were gradually displacing. Then, in 1919, a food shortage, especially of rice, occurred.

Suspected of hoarding the staple food, the establishments of the Lebanese, who had shops in at least 24 towns, were raided and looted in the so-called “anti-Syrian riots,” until the colonial administration intervened to protect them from further molestation.

By the 1920s, it had become clear that the railway would not solve the increasing financial problems of Sierra Leone, as the export of produce had stagnated instead of spiraling, due to lack of feeder roads.

A program for the construction of feeder roads gained momentum in the same decade. The Lebanese were among the earliest truck (lorry) owners.

Income, however, did not increase as fast as was expected. The establishment, worried over a stagnant colonial revenue at a time when increasing new demands for expenditure were being made, began prospecting for minerals in 1926. At the same time, much encouragement was given to the development of cash crops, such as coffee and cocoa.

Many minerals were discovered, the most important being iron in Marampa, 35 km (22 mi) east-southeast of Port Loko, gold in the Pampana river basin in the northern province, and, in 1930, diamonds in the Sewa river basin.

Other minerals such as platinum and chromite did not prove to be of sufficient economic interest. Their production fell quickly and stopped altogether within a few years.

A few European firms immediately undertook to mine while Africans also formed syndicates and began operations. The Lebanese, too, did not let this opportunity slip by. Gold mining needed little

technical knowledge, and enjoyed a short-lived boom during the 1930s. Production reached a peak in 1936, but thereafter gradually declined. By the 1940s, gold mining had been virtually abandoned.

Iron ore proved more promising, since smuggling of the ore was impossible. Having obtained a 99-year concession lease, the Sierra Leone Development Company (Delco) was formed to exploit the ore1 constructing a 83 km (52 mi) railway from Marampa to Pepel, at the mouth of the Sierra Leone River, where a jetty was built to export the ore.

Regular shipments amounting to 24,000 tons began in 1933 and had risen dramatically to about 3,000,000 tons a year when the company went bankrupt and closed in 1975.

Diamonds were discovered in Kono in 1930, but mining did not begin until 1932, after the Consolidated African Selection Trust (CAST) had obtained a license. In 1934, “sole and exclusive right” to exploit the diamonds for 99 years was granted to the Sierra Leone Selection Trust (SLST), a subsidiary of CAST. Diamond mining expanded more dramatically than that of any other mineral. The illicit mining that was also carried on made it difficult, however, to compile accurate production statistics.

Nevertheless, the advent of mining had major consequences for the economy as a whole. The search for alternative revenue, which had led to prospecting in the first place, was vindicated.

As mining contribution to colonial revenue increased from the 1930s onwards, especially during the Great Depression of that decade, so did the traditional customs revenue drop proportionately.

Mining also offered job opportunities, employing more than 16,000 in 1939, and paying better wages than in most other jobs. Consequently, not only did the colonial administration cease to be the principal employer of labor, but new employment centers arose in the Protectorate as well as in Freetown.

Agriculture was not adversely affected by mining activities, as agricultural production figures show a remarkable consistency. Without being revolutionized, agriculture found new markets for its products.

Certainly mining destroyed the soil where actual digging was done, but the effect was to be felt later. A boom in trading also occurred and a new class of petty traders arose to supply the consumer goods demanded by mine workers. Sierra Leone remained a supplier of raw materials to the metropolitan countries.

Nothing was processed in the country itself, and all manufactured goods still had to be imported.

Of importance, however, was the fact that the rise of mining led to a change in the composition of exports, by contributing to the relative decline in the value of agricultural exports, thus changing the pattern of one-and-a-half centuries of economic history. But, in the mid-1970s, agriculture still remained the main source of cash income for the ordinary people.

Diamond mining began in Sierra Leone in 1932. Here workers are seen digging for diamonds.

Important developments took place in the 1950s. Trade unionism became fashionable as a direct consequence of mining. But diamonds had become the quickest way of making money. Thus smuggling increased on an unprecedented scale, particularly as mining spread from Kono to the Kenema and Bo districts in 1954.

The ‘Diamond Rush’ was at its height. The self-governing administration of the day tried to stop the loss of revenue caused through smuggling by suppressing illegal diggers by force. It failed.

It thus accepted their presence as an accomplished fact and legalized private diamond mining by issuing licences. Pressure mounted in the 1960s to nationalize a “foreign company” which since 1950 had been contributing an average of two-thirds to the national revenue of Sierra Leone. Nationalization took place in 1971, with the Sierra Leone government taking 51 percent of the company’s shares.

As independence began to approach in the late 1950s, economic planners became obsessed with such questions as import-substitution, industrialization, and a full diversification of the economy. The results, however, were disheartening.

A number of industries failed and had to shut down because of inept management, shortages of raw materials which had to be imported, high production costs, or other reasons.

Those industries which survived did so because they enjoyed a monopoly or relied on “protection measures.” The consequence was that average consumers paid more for locally produced goods than they would have done for imported ones.

The socio-economic trends of the 20th century hardly justify any talk of development or progress. By the mid-1970s, Sierra Leone was still an exporter of raw materials, and an importer of manufactured goods, with the value of imports always exceeding that of exports.

Economic “development” on the whole was extractive rather than “productive.” A new dimension was added in the 1960s and 1970s by world inflation and frequent shortages of the country’s staple food, rice-developments which combined to make life unpleasant for ordinary people.

The Sierra Leone Produce Marketing Board, created to stabilize prices, did not always favor the farmer. While the Board undertook to develop plantations, especially of palm oil, some of the machines provided were idle some of the time because of lack of raw materials.

Agricultural development had failed to take place as planned, and ill-advised attempts to modernize agriculture, for example by the large-scale provision of tractors, proved expensive failures.

Economic hopes were therefore placed in the discovery of more minerals, and in the identification and introduction of better conceived agricultural projects.

POLITICAL CHANGES

The constitution of 1863 was still in force when it was superseded by the Slater Constitution (named for Sir Ransford Slater, governor from 1922-27) in 1924. After World War I, the National Congress of British West Africa was formed in 1920, to present African grievances to the imperial government.

It demanded, among other things, the abolition of racial discrimination in the public service, the granting of power and responsibility to Africans, and the creation of the West African university.

Nothing specific resulted, but Governor Slater nevertheless decided to make some concessions to the Africans in a new constitution. The unofficial membership of the Legislative Council was increased from four to ten, seven being appointed by the governor, and three being elected to represent the Colony.

Of the seven appointed, three had to be paramount chiefs to represent Protectorate interests. Thus the Slater Constitution allowed the elective principle, denied in 1863, and for the first time provided for the representation of the Protectorate on the Council, which had been enacting laws for it since 1896. But the governor had only to make a token concession. For he remained convinced that official control over policy must remain.

Up to 1937, the Protectorate had been administered on the basis of a kind of quieta non movere (“let sleeping dogs lie”) policy. With the rise of mining and labor movements, it was however discovered that chiefdom administration as it then existed was unsuitable for “development.”

Thus J.S. Fenton was sent to Nigeria to study the system of Native Administration there, and on the basis of his report, a similar system was adopted in Sierra Leone.

Paramount chiefs had to give up their traditional revenues in exchange for a fixed salary, chiefdom courts had to have a regular composition, and treasuries were established to keep revenue to be used for salaries and “development projects.” There was, however, no haste to introduce these measures.

Chiefdoms that so wished would adopt the new Native Administration, but none was forced to accept it. Tiny chiefdoms were encouraged to amalgamate to make the project meaningful.

The introduction of Native Administrations thus proceeded slowly. At the time of independence in 1961, not all chiefdoms had Native Administrations.

World War II ushered in many changes favorable to African demands for self-government. But national self-determination, accepted as a principle for the political rehabilitation of Europe, was denied by Britain to her African colonies, including Sierra Leone.

Both the Soviet Union and the United States, however, put continuous pressure on Britain to move towards such self-determination. The electoral victory of the British Labour Party in 1945, shortly before the end of World War II, also increased the prospects for advancement of African interests.

The principle of eventual independence for African colonies was gradually accepted, and the Colonial Development and Welfare Acts (1940-45) were passed in Britain in order to facilitate the process by granting socioeconomic assistance to African territories.

In 1946, a Protectorate Assembly was established, and district councils were introduced. Each district council was to represent its own district, all paramount chiefs being members automatically.

The district councils were to obtain an imprest (advance of funds) on the chiefdom local tax to carry out development projects within the district. They were also to elect members to the Protectorate Assembly which was to discuss matters concerning Protectorate welfare as well as matters referred to it by the governor in council.

Governor Hubert Stevenson (term of office 1941-48) introduced a new constitution in 1947 which gave a majority to elected members in the Legislative Council, and allowed Protectorate Africans greater participation in the management of the affairs of the country.

Because of opposition from entrenched Krio interests, which became united in the National Council of Sierra Leone (N.C.) to oppose the provisions of the constitution on the unreasonable grounds that the Protectorate and its inhabitants were foreign, the constitution was not passed until 1951.

By then Protectorate interests too had crystallized into the Sierra Leone People’s Party (S.L.P.P) under the leadership of Dr. M.A.S. (later Sir Milton) Margai. Indirect elections were held, and after much political maneuvering, the S.L.P. emerged with 15 seats, while the N.C. obtained 5 out of an unofficial membership of 21 in the Legislative Council.

The governor, Sir Beresford Stooke (in office 1948-53) therefore asked Dr. Margai to nominate six from his party to sit on the Executive Council. Dr. Margai himself became chief minister.

Elections were due in 1957. But before this, in 1955, there were serious riots in Freetown and in many parts of the Northern Province. These came to be called anti-chief riots, since they were mainly directed against oppression by chiefs.

As part of the preparations for the elections, however, following the recommendations of an electoral reform commission headed by Sir Keith Lucas, a number of reforms were introduced.

The Protectorate Assembly was abolished. The Legislative Council (renamed the House of Representatives) was given a membership of 57, including 12 paramount chiefs, each representing a district.

In addition, the chief minister became premier. Direct elections were then held for the first time, and the S.L.P.P. won 44 seats. In the meantime, a number of mushroom parties had emerged. But the official opposition was the United People’s Party (U.P.P.), led by C.B. Rogers-Wright, a lawyer who was later to be disbarred for professional misconduct.

In 1958, the S.L.P.P. split because of differences between Dr. Margai and his younger brother, Albert, a lawyer with radical inclinations, who was supported by Siaka Stevens, the leading trade unionist of the time.

The new splinter group formed the People’s National Party (P.N.P.). All parties agreed, however, to form a United National Front to negotiate for independence.

At the constitutional conference in, London in May 1960, it was agreed that April 27, 1961 wld–btke date for regaining independence. But Siaka Stevens announced himself unable to sign the constitutional document, due in part to differences with Albert Margai.

Therefore the P.N.P. split, and what began as an ”elections before independence” movement (known as the Stevens faction) was officially transformed into the All People’s Congress (A.P.C.) party, drawing much of its support from discontented urban groups and Northern elements.

The A.P.C. was quite popular and within two months of its formation won the elections to the Freetown City Council. The S.L.P.P. won the general election held in 1962, but the A.P.C. had emerged meanwhile as the strongest opposition party.

The A.P.C. won even more support when Sir Milton died in 1964, and was succeeded by his brother Albert. A number of influential S.L.P.P. members declared for the A.P.C.

By 1966 the S.L.P.P. had become unpopular following the declaration of the intention of Sir Albert to introduce a one-party system as well as a republican constitution, when the country was

I.T.A. Wallace-Johnson campaigning for the All People’s Congress (A.P .C.) in the 1962 general election.

Sir Milton Margai campaigning for the Sierra Leone People’s Party (S.L.P .P .) in the 1962 general election.

suffering from economic difficulties and food shortages. After bitter opposition from the A.P.C., intellectuals, and others, Sir Albert declared that he had dropped both issues, but not before the republican bill designed to introduce a non-executive presidency had passed the house.

Sir Albert also announced that he had discovered a plot against the government led by Col. John Bangura, who was then sent overseas to a diplomatic post in the United States.

In these circumstances, Sir Albert called general elections in April 1967. After a close contest, the official figures announced were S.L.P.P., 32; A.P.C., 32; and Independents, 2. But the governor-general, using his constitutional powers, decided that the A.P.C. had won the election, and swore in Siaka Stevens as prime minister.

The military then intervened, the force commander, Brigadier David Lansana, announcing that no party had had a majority. The following day, his senior officers arrested Lansana, sent him off to a diplomatic post, and created a National Reformation Council (N.R.C.) under Col. Andrew Juxon-Smith.

The N.R.C. then set up a commission of enquiry into the conduct of the 1967 general elections, which concluded that the A.P.C. had won. Exactly a year after it had come into existence, the N.R.C. was overthrown by a revolt of non-commissioned officers, and John Bangura was recalled from abroad to head the army. He pledged to return the country to civilian rule, which he did within a week.

Siaka Stevens was again sworn in as prime minister, but this time as prime minister of a national government which included S.L.P.P. ministers. After some time, however, the S.L.P.P. members thought that they would be better off if they constituted themselves into an official opposition.

This was because there had been clashes with the A.P.C., particularly after mass arrests of S.L.P.P. supporters had taken place in late 1968, and faction fights had occurred in several places. Thus within a year, an all A.P.C. government had been constituted.

In 1970, two former cabinet ministers resigned their party membership and joined other younger elements to form a new party, the United Democratic Party (U.D.P.) under the leadership of Dr. John Karefa Smart.

Karefa Smart had once been a minister under Sir Milton Margai, but had resigned and joined the A.P.C. when Albert Margai took over. The U.D.P. accused the A.P.C. leadership of authoritarian tendencies. Violent clashes occurred between the U.D.P. and A.P.C. supporters. The government then arrested the U.D.P. leaders and proscribed the party itself.

Shortly after, there was an attempted coup by Brigadier John Bangura who had become the force commander. The coup was, however, unsuccessful. Tried and found guilty by a court martial, Bangura and others were executed.

The next political development was the emergence of a movement towards the declaration of a republic. It was argued that it was colonialist for the Queen of England to be head of state. To cast off this “last vestige of colonialism,” a republic should be established.

Since this implied a change in the constitution, the republican bill had to be introduced and passed in two successive parliaments with a two thirds majority, a general election having been held in between.

With slight modifications, the republican bill passed by Albert Margai in 1966 was re-introduced and passed. Sierra Leone thus became a republic in April 1971 with the chief justice, C.O.E. Cole, as ceremonial president.

Two days later, an amendment was adopted creating an executive presidency, with Siaka Stevens as the first executive president of Sierra Leone.

Elections were due to be held in 1973, and on nomination day the A.P.C. won 46 out of 97 seats unopposed. The S.L.P.P. charged that thugs broke into nomination centers and destroyed their papers, preventing them from entering nomination centers at all in 6 districts out of 12. The S.L.P.P.

then withdrew from the general elections altogether on grounds that they were in physical danger if they contested them, while those who had succeeded in having themselves nominated withdrew their nominations. In addition, the S.L.P.P. stated there was no point in contesting an election when half the seats had already been won by the government.

In July 1974, a plot to overthrow the government was uncovered involving ex-Minister Dr. Forna and 14 others. Found guilty, they were executed in July 1975.

Thus from 1973 to 1977, there was no official opposition in parliament, until events early in the year precipitated general elections, which would normally have been held in 1978. As chancellor of the University of Sierra Leone, President Stevens was conferring degrees on graduates when students staged a demonstration and disrupted the proceedings.

The students made a number of demands, including, among other things, the holding of free and fair elections. Parliament was dissolved, and elections announced.

On nomination day in April, the A.P.C. obtained unopposed all the seats in four Northern districts, and one Southern district. The S.L.P.P. charged that it had been prevented from nominating its candidates by A.P.C. stalwarts.

Nominations in Bo district, where eight seats were in contest, were postponed, to be held later, with the A.P.C. winning all unopposed. In areas where the S.L.P.P. was able to nominate candidates, however, it won 15 seats. It then constituted the official opposition in the Sierra Leone Parliament.