A HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

The Republic of South Africa occupies the southern-most area of the African continent, comprising 435,868 square miles. It is about half the size of Africa’s largest country, Zaire, or about the size of California and Texas combined. It is bordered by Namibia (South West Africa) to the northwest, Botswana and Zimbabwe to the north, and Mozambique and Swaziland to the east. South Africa completely surrounds the independent nation of Lesotho. To the east is the Indian Ocean; to the west, the Atlantic Ocean.

Most of South Africa consists of an interior plateau that rises from 600 to 2,000 meters (2,000 to 6,500 feet) above sea level. A narrow plain frames the plateau along its 2,700 miles of coast.

Highest in the east and southeast, the plateau gradually descends in the northwest toward the Kalahari Basin. In the southern Transvaal and the Orange Free State the plateau rises to between 1,200 and 1,800 meters (4,000 to 6,000 feet) in a triangular shape. At the northern edge of this triangle is a ridge called the Witwatersrand that rises to 1,500 meters (5,000 feet). The ridge runs from northwest to southeast, forming a major drainage divide. Most of the country’s mineral resources are found in this area of the plateau.

The western half of the plateau is about 900 meters (3,000 feet) above sea level. It is made up mostly of dry flatland called the Karoo, which gently merges with the Namib and Kalahari deserts in the west and northwest.

A high ridge known as the Great Escarpment runs along the plateau, separating it from the coastal areas. Along the eastern coast it is known as the Drakensberg; as it turns westward it becomes successively the Stormberg, Sneeuberg, Nieuwveld, and Komsberg ranges. Turning toward the northwest, the escarpment is known as Roggeveld Berg.

The Orange River system-its major tributary is the Vaal-rises in the Drakensberg and flows westward for 1,900 km (1,100 miles) to the Atlantic Ocean, draining most of the plateau. Hundreds of smaller rivers, such as the Great Fish, Kei, Pongola, Umzimvubu, and the Tugela, rise in the Drakensberg and flow eastward into the Indian Ocean.

The Limpopo is the other major river system. It rises in the northern slopes of the Witwatersrand and flows eastward to the Indian Ocean, draining most of the central and northern Transvaal.

Most of the country relies on dams or underground water for water supply. None of South Africa’s rivers are navigable. Deep water ports are located on the Indian Ocean coast, as far westward as Cape Town, and north on the Atlantic Coast to Saldanha Bay.

Except for an area in the northern Transvaal, South Africa is subtropical, lying south of the Tropic of Capricorn, between 25 and 35. Generally, the temperatures are fairly constant throughout the country, although the east coast is warmer and receives more rainfall than the Atlantic seaboard.

The plateau itself rises from south to north. This rise results in similar temperature ranges being found throughout the country. For example, the mean annual temperature in Cape Town is 1 7 Celsius, whereas further north, in Pretoria, it is 17.5 Celsius.

The east coast is warmed by the Agulhas Current (the southern part of the Mozambique Current). which flows in the Indian Ocean and, as a result, receives the most rain. Durban on the east coast receives 1.068 mm (42 inches) of rain annually, in contrast to Port Nolloth on the Atlantic coast which is cooled by the Benguela Current and receives as little as 58 mm (2.3 inches) annually.

The summer is the rainy season-from November to April-when temperatures run from highs of 21-24 degrees Celsius. The winter is usually dry-April to October-when daytime temperatures run from lows of not less than 5-10 degrees Celsius.

In 1993, South Africa’s population was estimated to be about 32,589,000. Africans formed the majority of the population, and were said to number 23,016,000 or about 71 percent; Europeans were said to number 5,149,000 or some 16 percent. Coloureds were said to number 3,402,000 or close to 10 percent and Asians 1,022,000 or about 3 percent.

THE AFRICAN PEOPLE AND THEIR HISTORY

Recent archaeological evidence has stilled the debate as to whether the Bantu lived in the southern African region before the Europeans arrived. Archaeological research has confirmed

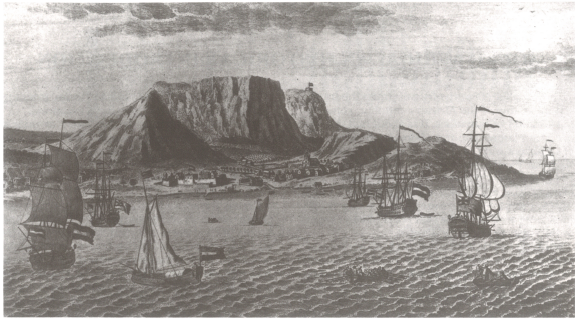

The Table Bay anchorage, north of Cape Town, showing Dutch and British ships, en route to the East, calling at the Dutch settlement in1720. Reproduction of an aquatint by Van Rijne.

the presence of Early Iron Age people, the ancestors of the present-day Bantu -speaking peoples of South Africa, living on the northern plateau as early as 270 A.D. The majority of Early Iron Age sites have been found in the eastern lowland valley and coastal regions of what is now the Transvaal, Swaziland, Zululand, and Natal. A synthesis of the recent evidence is presented in Paul Maylam’s A History of the African People of South Africa ( 1986).

Stone Age hunters and gatherers known as San (Bushmen) had also occupied much of the eastern lowlands and northern plateau. They were gradually pushed southward to the Cape and westward to the flatlands of Namibia by the advances of the Bantu. The San shared the area with the Khoi Khoi (Hottentots), a closely related people who, in addition to hunting and gathering, grazed sheep and cattle.

Egg-shell beads and other materials that belonged to the San have been found at Bantu settlement sites, indicating that the two groups coexisted, intermarrying and absorbing cultural characteristics from one another. Further evidence of the intermingling of the groups is a distinctive click sound in the speech of Bantu groups, the Nguni in the south and Sotho speakers in the interior of the plateau. Still heard in the speech of the San, the click is a language trait that originated with the San and the Khoi Khoi.

Starting about 1000 and continuing until the

1400s, Late Iron Age Bantu farmers had settled most of the fertile areas of the eastern half of South Africa.

Today, the Bantu-speaking peoples of South Africa are classified into two main linguistic groups: Nguni and Sotho. Nguni speakers inhabited the southeastern region of South Africa between the interior plateau and the Indian Ocean, and the area stretching between present-day Ciskei and Swaziland. The Sotho settled principally in the interior plateau.

Northern Nguni

Until the 19th century, Nguni speakers ranged along the coastal areas in numerous and probably fairly small chiefdoms. By the end of the 1 700s, however, political consolidation had begun to occur among the northern Nguni and several powerful chiefdoms arose. Among these were the Ngwane, the most northerly of the power blocs, who had settled north of the Pongola River in what is now southern Swaziland.

The Ndwandwe occupied the area south of the Pongola River; they expanded by incorporating many smaller chiefdoms, gradually extending control from the Pongola to the Black Mfolosi River.

To the south were the Qwabe, who controlled the area between the Mhlatuze and Tugela Rivers. Just south of the Qwabe were the exceptionally powerful Mthethwa, who controlled crossing points and thus trade over the lower Mfolosi River. In the early 1800s, Dingiswayo, then the Mthethwa chief, expanded control over the Zulu and Buthelezi lineages, eventually conquering and incorporating the Qwabe as well.

On Dingiswayo’s death, the Mthethwa chiefdom was divided by a quarrel over succession. Shaka, a chief of the Zulu sub lineage of the Mthethwa and a compatriot of Dingiswayo’s, seized the chieftaincy. Shaka centralized power, built up a well-disciplined army and conquered the peoples around him.

Much of the early history of the African people of South Africa built up to the climactic events of the Mfecane (“Upheaval”) in the 1820s. The Mfecane came about as Shaka consolidated the Zulu nation state through military conquest, causing thousands of people to flee his armies and abandon their fields and cattle. These refugees created turmoil among people living in the peripheral areas when they invaded settled areas in search of land and cattle.

Disabled by the Mfecane, the peoples of the area were unprepared for the encroachment by European settlers, which began to occur in the late 1830s and the 1840s.

Southern Nguni

The Mpondo, Mpondomise, Bomvana, Thembu, and Xhosa were among the early Bantu settlers in the southern area of the eastern Cape, beyond the Mzimkhulu and Mzimvubu Rivers and the Drakensberg range.

By the mid to late 1600s, Xhosa lineages had united in a single chiefdom under Chief Tshawe. The kingdom remained united for nearly 100 years until two brothers fought over the succession to the throne and divided the kingdom. Two separate chiefdoms were established by the warring sons of Chief Phalothe Rarabe lineage of the Ciskei and the Gcaleka of the Transkei.

Because of their southerly location, the Xhosa were the first Bantu group to come into contact with the European settlers. The Xhosa fought European settlers in a series of wars known as the Frontier Wars that began in 1779 and continued until the late 1800s.

Sotho

Tracings of Sotho people in the northern Transvaal and eastern Botswana date to the 11th century. By the end of the 18th century Sotho communities were occupying large areas throughout the interior plateau.

The Sotho people are generally grouped into three major subgroups based on language and settlement patterns that developed as a result of the Mfecane. These broad groups are: the Tswana, Basotho, and the northern Sotho or Pedi and Lobedu (Lovedu).

Tswana

Unlike the northern Nguni, the Tswana did not form centralized chiefdoms or states. Rather, when disputes over land or inheritance occurred, one group hived off from another and created an independent chiefdom. By the early 1800s, Tswana lineages were occupying the plateau from the Witwatersrand northward and westward, down to the flatlands and Botswana.

All Tswana lineages trace a common ancestry to three main chiefdoms that inhabited the Witwatersrand between the 13th and 16th centuries: Morolong, Masilo, and Mokgatla. Historically, the Masilo lineage divided into two major groups-the Kwena and Hurutshe chiefdoms. By the 18th century, the Hurutshe had become one of the most powerful of Tswana chiefdoms. Its territory extended from present-day Rustenburg to the Pilanesberg.

By the 17th and 18th centuries the Kwena chiefdom had subdivided into the Ngwaketse under chief Moleta and the Ngwato under chief Mathiba. Ngwaketse power rivaled the Hurutshe and the two groups fought continually. The Ngwaketse chased the Ngwato to the north where they made their capital at Shushong in the late 1700s.

The ancestors of Mokgatla divided into the Kgatla lineage and then subdivided again into smaller lineages, among them the Pedi and the Tlokwa chiefdoms.

The third main Tswana lineage group was the Rolong. They became a powerful group under Tau in the southwestern Transvaal and northwestern Cape.

When the Mfecane occurred, the Tswana were particularly vulnerable to the waves of refugees because they were a fragmented people who had had little or no experience with centralized rule or methods of resistance.

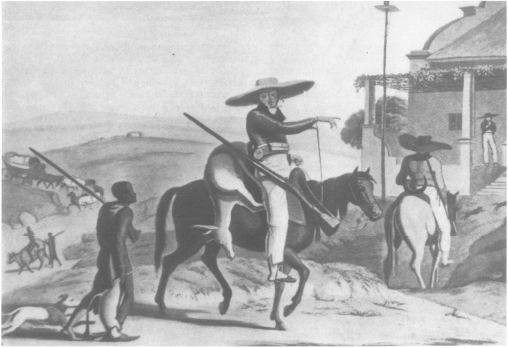

Soldiers of the Dutch East India Company at the Cape of Good Hope in the mid-17th century.

Basotho

The southern Sotho, the Basotho, also trace their lineage groups to Kwena and Kgatla. Most southern Sotho are descended from the Fokeng and Kwena lineages. The Fokeng may have been the first Bantu group to settle in the Witwatersrand, probably about 1500. The Fokeng were forced southward to the Caledon River by the Kwena who settled the area in the upper Caledon River Valley.

Northern Sotho

The Pedi constituted the predominant lineage of the northern Sotho. A heterogenous group, they incorporated peoples from the Maroteng and Tau groups into their chiefdom. The Pedi occupied the northeastern region of the plateau, around present-day Pretoria. They developed a powerful military force, conquering peoples throughout the northern plateau, as far south as the Vaal River and west as far as Rustenburg. The Pedi also controlled the trade route to Delagoa Bay. They were at the height of their power by the 1820s.

THE EUROPEANS AND THEIR HISTORY

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to make contact with southern Africa. Seeking passage to the Indies, Bartholomew Dias was the first Portuguese to reach the Cape of Good Hope (which he called the “Cape of Storms”) in 1487-88. Another Portuguese navigator, Vasco da Gama, followed in 1497, and went on to open the sea route to India. But the southern tip offered the explorers nothing of value and so nearly 200 years passed before a permanent European settlement was established.

By the 17th century, the Portuguese, Dutch, and British had established worldwide trading networks. They needed stations to resupply their ships. In 1652 the Dutch East India Company set up a settlement at Table Bay under the leadership of Jan Van Riebeeck. There the company established granaries, storehouses, vegetable plots, and a hospital. The Dutch also traded for meat with the African people there, the Khoi and San, whom they called “Hottentots.”

By 1708 few immigrants had come to the Cape, and the European population-Dutch speaking and Calvinist-numbered only about 1,440. Slowly, however, the small settlement grew. More settlers came from Holland and Germany, as also did Huguenot refugees from France. Gradually the settlers ventured beyond the mountains protecting Table Bay to enter the valleys where the soil was suitable for growing wheat and grapes.

Unable easily to enslave the indigenous San and Khoi Khoi in sufficient numbers, the European farmers began to import slave labor from Angola, Madagascar, and the East Indies. Interbreeding between slaves and whites produced a mixed group called the “Coloureds.”

British Occupation and Rule

The successful rebellion of American colonists against the British, which began in 1776 and resulted in independence in 1783, created a promising precedent for other peoples also subjected to colonial rule. Independent-minded Dutch settlers in South Africa, angered by the Dutch East India Company’s insistence on decent treatment of slaves, rebelled against company rule. In 1795 they declared independent republics in Swellen- dam and Graaff Reinet.

The republics were short lived and led to a worsening of relations between settlers and the company. Later that year the Dutch East India Company surrendered authority to a British expeditionary force, which administered the Cape Colony from 1795 to 1803. The Netherlands took control again. In 1803, under the terms of the

Dutchfanners of the Cape Colony retuming from a hunt in 1801.

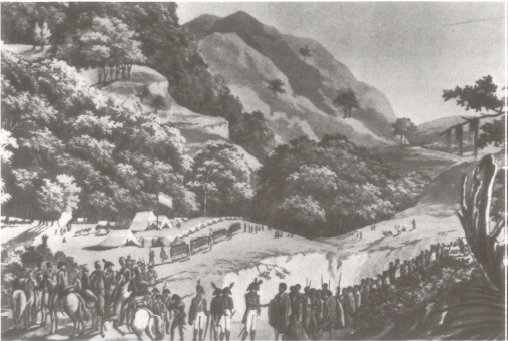

In 1804 the Dutch Governor Jan Janssens (q. v.) and Ngqika (q. v.) of the Rarabe branch of the Xhosa met in the Kat River valley to discuss the borders of Cape Colony.

1802 Peace of Amiens, the Netherlands, subject to French control, took over the Cape and established the Batavian Republic. But when in 1805 fighting began in what were to be known as the Napoleonic Wars, the British soon moved to take over the Cape once more, which they did in 1806. At the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, in 1814, the Cape was officially ceded to Britain.

The British were not particularly interested in establishing a permanent settlement there. In 1806 the Cape was a forlornly barren place, with few resources and a meager population consisting of about 30,000 Hottentots, 26,000 Dutch, and 30,000 slaves. But Britain placed a high value on its strategic location, which safeguarded the lucrative southern sea route from Europe to India.

Relations between the Dutch-speaking farmers (the Boers) and the English-speaking administrators were never genial. The Boers were a solitary, inbred people who wanted to live by their own codes, away from neighbors and restrictions.

As the Boers pushed further out from the Cape in search of grazing lands, they encountered the Xhosa who had settled in the eastern Cape, along the Fish River. Skirmishes between the two groups over lands and grazing areas had occurred regularly from 1779 on. After decades of clashes, the Fish River was made the eastern boundary of the Cape Colony and the Orange River its northern boundary.

THE Voortrekkers

In the early 1800s the Boers eventually left the Cape Colony altogether. Infuriated by British policy that demanded fair treatment of Africans, the Boers defied the British Colonial Office by resisting arrest and attacking Coloured troops sent to arrest one of them. Five Boers were condemned and hanged for their defiance of British authority in what was called the Rebellion of Slagter’s Neck.

European Christian missionary activity on behalf of the Africans further disrupted the Boer way of life. The Boers interpreted the Old Testament to say that they were the chosen race of God and that the Africans were meant to be their servants.

Yet missionaries of such groups as the London Missionary Society and the Moravian Brethren preached equality for all races and fought for the rights of non-whites in South Africa. (The Dutch Reformed Church was the exception for it held the view that their mission was to guard white civilization.)

In 1820, Governor of the Cape Colony Lord Charles Somerset arranged to have between 4,000 and 5,000 unemployed British peoples sent out to settle the area beyond the Great Fish, Keiskamma, and Kei rivers.

The British hoped they would become a buffer between the Xhosa and the Cape Colony. But the Boers, who were already competing for land with the Xhosa, were threatened by the presence of more people in an already overpopulated area.

Finally, when English was declared the official language of the courts and then when slavery was abolished in the 1830s, the Boers had had enough. Between 1835 and 1837 about 10,000 Boers left

the Cape Colony with their families and belongings in search of land and freedom from the constraints imposed by the British. They became known as the Voortrekkers (literally the “Front Trekkers,” or the vanguard).

The Voortrekkers had unknowingly set out at about the time Zulu power was at its height, and when the chaos created by Zulu military expansion was at its worst. Yet the Boers, due to the superiority given them by their firearms, and the skillful use they made of their wagons, eventually overwhelmed the Zulu.

The most famous battle fought between Zulu and Boer, was in 1838 at the Ncome River, forever after called Blood River by the Boer. To avenge the death of Boer leader Pieter Retief (q.v.) at the hands of the Zulu, a group of Boers led by Andries Pretorius defeated’the Zulu king Dingane. Shaka’s successor, in a bloody battle in which 3,000 Zulu were killed.

The Zulus retreated north of the Tugela River and left the Boers alone. Meanwhile, the Boers settled the rich arable lands of Natal, recently abandoned by the peoples fleeing Shaka’s armies. There the Boers established the republic of Natalia.

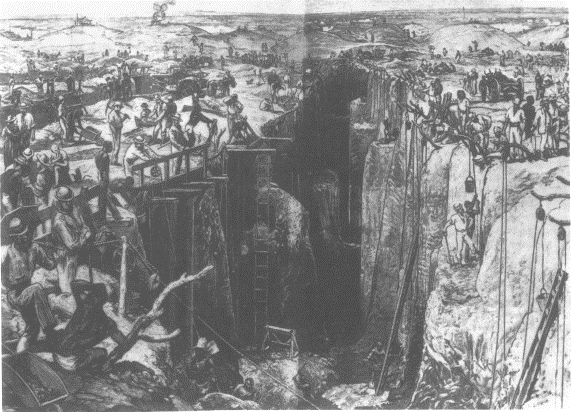

“The Big Hole”: The diamond diggings of Kimberley, in the Orange Free State, as they appeared in 1870.

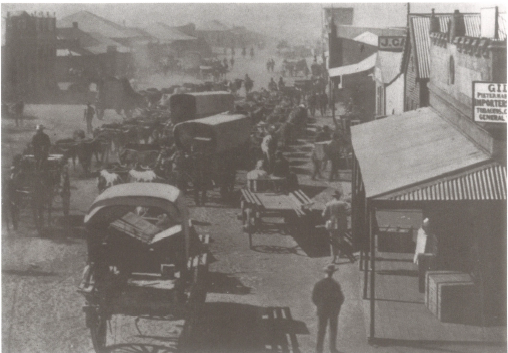

Johannesburg as it appeared when it was little more than a gold mining camp, soon after the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886. Today Johannesburg is the largest city in southern Africa.

Britain, however, was unwilling to allow the Boers to have access to the sea and annexed Natal in 1843 under the pretext of protecting the rights of dispossessed Africans.

Once again the Boers moved to escape British rule. This time they left Natal and joined other trekkers who had settled between the Orange and Vaal Rivers. Initially, the Cape authorities had tried to annex each republic as soon as the Boers created it, but soon realized that the cost and difficulty of controlling widespread areas made annexation impracticable.

Therefore, by the terms of the Sand River Convention of 1852, the British granted the Boers the right to self government north of the Vaal River. This area became known as the South African Republic-the Transvaal. Subsequently, in 1854, the Convention of Bloemfontein granted the same rights to the Boers who had established the Orange River Sovereignty, which now became known as the Orange Free State. Thus the second Boer republic was born.

The British Colonial Office had long had an ambivalent attitude toward the colonies in South Africa. Initially refusing to become financially or militarily involved, Britain gradually committed more resources to expanding British influence. The Cape Colony had gradually added territory extending British South Africa up to the Orange River in 1847, and incorporating British Kaffraria east of the Great Fish River in 1866.

In 1868, when a conflict between the Boers of the Orange Free State and the people of Lesotho led to the possibility that fighting would spread to the Cape Colony, Britain agreed to protect the Sotho people of Moshoeshoe from advances by the Boer.

A federation of British colonies under the leadership of the Cape had first been attempted by the British Colonial Office between 1857 and 1859. But when diamonds were discovered in Griqualand in 1867, the British ended all talk of federation.Instead, the Cape Colony annexed Griqualand West in 1871, despite the counter claims of the Orange Free State, the Transvaal, and Tswana and Griqua chiefs.

After 1875, however, Britain again talked of forming a federation. The Transvaal refused to join, even though it was nearly bankrupt and had been militarily humiliated by the Pedi chief Sekhukhuni.To demonstrate to theTransvaal the advantages of federation with the Cape and Natal, Britain showed its power by annexing Zululand in 1877.

When the British invaded their land in January 1879, however, the Zulu fought back, defeating the British at the battle of Isandlwana Hill. While the British ultimately prevailed over the Zulu, this defeat did much to undermine confidence in British foreign policy as well as in Britain’s military capabilities.

Having failed to achieve its ends by persuasion, Britain proceeded to annex the Transvaal in 1877. The Transvaal Boers opposed the British troops and defeated them at Majuba Hill in 1881. In the same year, Britain then reconsidered its annexation policy, and restored the Transvaal to Boer control.

Diamonds and Gold

The discovery of alluvial diamonds in the border areas of the Orange Free State and Cape Colony in 1867, and the subsequent discovery that diamonds were also to be found in rock (kimberlite). brought thousands of prospectors to South Africa. Their prevailing attitude was “each-man-for-himself.”

The confused and anarchic conditions that resulted were finally brought into a semblance of order by the English entrepreneur and empire builder Cecil Rhodes. who grouped the major mining houses into a single monopoly, DeBeers Consolidated Mines, Ltd. By 1881 diamond prices had been stabilized through a Central Buying Organization.

When gold was discovered in 1887 in the Witwatersrand area, near Johannesburg, the diamond magnates quickly moved in to buy up great tracts of land. Because gold in the Witwatersrand was low yield and required mining well below the surface, mining operations needed extensive capital outlays and employed thousands of manual laborers. Capital requirements therefore limited the competition to a few.

The discovery of diamonds and gold changed the course of South Africa’s development for ever. A predominantly agricultural economy was suddenly transformed into a mining economy heavily dependent on cheap, abundant manpower. The governments of the Cape and Transvaal became instruments for the mining industry, helping it to obtain the labor it sought at the lowest rate.

A new city, Johannesburg, grew up almost overnight as thousands of people flocked to the Witwatersrand. In a short time Uitlanders (“foreigners,” especially those not speaking Dutch) came to outnumber Afrikaaners, by 7 to 3. Most of the capital and white mine workers were Uitlanders, and they controlled most of the gold wealth.

Paul Kruger. president of the Transvaal, seized the opportunity to replenish his treasury by imposing taxes on the gold mining industry and by levying high import fees, all the while maintaining political control by refusing to extend the franchise.

The Uitlanders and the British Colonial Office were frustrated by Kruger’s attitude and policies. Relations reached a breaking point when Cecil Rhodes now governor of the Cape Colony and who was seeking British control of the Transvaal, persuaded his friend Leander Starr Jameson to lead a raid on Johannesburg, rally the Uitlanders (who had been provided with arms for the occasion), and overthrow President Kruger.

The raid, which took place in 1895-96, was a failure. The Uitlanders failed to rise up, Jameson was arrested, and Rhodes was obliged to resign as governor of Cape Colony. The Jameson Raid became a symbol to Boers throughout the country of British perfidy.

The South African War

The South African War of 1899-1902, also known as the Boer War or the Anglo Boer War, was fought between Britain on the one hand, and the two Boer republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State on the other.

The issue at stake was that the Boers were determined to maintain the sovereignty of their republics, while the British, for their part, were equally determined to bring the South African region into a union under their control. War became inevitable when both Paul Kruger. president of the Transvaal, and Joseph Chamberlain, British colonial secretary, showed themselves equally intransigent.

Kruger refused to consider the extension of political rights to the increasing number of Uitlanders in the Transvaal, while Chamberlain, together with Alfred Milner the British high commissioner in South Africa, believed in extending the sway of British imperialism over southern Africa in general, and the gold-producing Transvaal in particular.

While the British were indisputably superior in strength, the Transvaal Boers hoped for support from Britain’s European rivals, especially Germany, and also expected help from other Boers living in the Orange Free State, Natal, and the Cape Colony.

In the first phase of the war, the Boers were successful, but when British reinforcements arrived,the Boer army, numbering about 70,000, found itself opposed by British forces of about 300,000. By 1900 the British had defeated the Boer armies, and occupied the republics, and Kruger had been obliged to flee to Europe.

The war, however, was not over. For 15 months Boer commandos waged a guerrilla war against the British, and controlled large tracts of the countryside. When Boers invaded the Cape Colony, the British redoubled their efforts and systematically ravaged Boer territory, destroying livestock, farmlands, and homes.

Large numbers of Boer civilians were placed in concentration camps, where many died. The foreign aid the Boers had been expecting failed to materialize, as did the hoped-for help from the Cape Colony Boer population. In the end the Boers were obliged to concede.

The terms of the Peace of Vereeniging, concluded on May 31, 1902, made the Boer republics British territory, but promised the Boers local autonomy once the reconstruction period was over.

The British, however, made an important concession to Boer nationalists by mentioning nothing in the peace treaty about the civil rights of black South Africans. Thus was a clear pathway marked for the eventual establishment of racial segregation and inequality in South Africa.

The conglomeration of territories that resulted from the Peace of Vereeniging by no means made up a unified nation. But, in the decade that followed, first steps leading in that direction were to be taken.

Several political parties were formed, including the Het Volk (“The People”) Party in the Transvaal in 1905, and the Orangia Unie (“Orange Union”) Party in the Orange River Colony (as the British had re-named the Orange Free State) soon after-ward. Both stressed unification for a responsible South African government.

In the Cape Colony, the previously all-Boer Afrikaner Bond Party became the South African Party, and included British members. But British High Commissioner Milner continued to believe firmly in British control of the nation.

In 1907, nonetheless, the newly elected British Liberal government overturned this line of thinking, granting complete self-determination to the Orange River Colony and the Transvaal. The Het Volk and Orangia Unie Parties became the governing political units of each. With their independence restored, the Boers were in a much better position to consider a voluntary unification of South Africa.

In May 1908, the building of intercolonial railways occasioned a nationwide conference in Pretoria. At this conference a national union was discussed in earnest, and led to the convocation of a national convention in 1908-1909.

The convention resolved that there be complete equality of the Afrikaans and English languages, and that one legislative authority be established for the nation (although still subject to British authority). A constitution for a Union of South Africa was drafted.

The Union was to have a British-appointed governor general, and would consist of four provinces, each with its interior government, which would report to the central government. The vote was to be extended to all European males. No consideration was given to, and no provision made for, the civil rights or destiny of the black population.

When talks on a constitution got under way, African political groups mobilized. Since the constitution had to be approved by the British Parliament, the African People’s Organization and the South African Native National Conference sent deputations to England to protest their disenfranchisement.

Despite the protests of the Africans, the constitution was ratified and the Union of South Africa was proclaimed on May 31, 1910. The conference, unable to resolve its differences over the franchise, had agreed to allow each of the four provinces to retain their existing policies. This meant that the Cape Coloured would retain the right to vote and could be denied it only by a two-thirds vote of the entire Parliament. This agreement was sour wine for the millions of black Africans who were to find themselves completely dominated by a white minority.

General Louis Botha, leader of the South African Party who had been a military figure on the Boer side during the recent war, became the Union’s first prime minister. In trying to reconcile British and Afrikaner interests in a true union, Botha alienated the more conservative members of his party who feared domination by the British. Led by General J.B.M. Hertzog, this group broke off from the South African Party and formed the Nationalist Party.

Hertzog advocated a “twin stream” policy of development in which Afrikaner interests would develop alongside English interests. To achieve this he proposed that the Afrikaans language be used in schools, business, and government, and that money raised from increased taxation on the mining industry would support development of Afrikaner institutions.

Botha and his party continued to control the government but the seeds planted by Hertzog would grow into a dominant Afrikaner movement in the years to come.

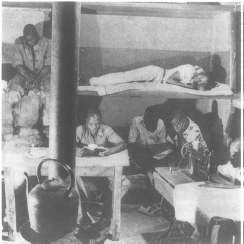

Throughout the 20th century South Africa has not had enough labor to meet the demandfordangerous work in the mines which produce the country’s wealth. African mineworkers are therefore hired under contract, not only from South Africa but also from other countries in the region, such as Lesotho, Angola, Mozambique, or Malawi. While under contract, workers are obliged to live in dormitories on the mining compounds. Families are not allowed, and living conditions are reminiscent of those in an army barracks, as this picture shows.

The rise in Afrikaner nationalism was paralleled by the depriving of Africans of their rights. Legislation such as the Natives Land Act of 1913 forced Africans off their lands and into the urban areas and the wage economy. The African National Congress (ANC), established in 1912, sent a representative to the king of England to protest the eviction of the rightful landowners under this act, but without result.

Between the Wars

At the outbreak of World War I, the question of whose side South Africa would take dominated the political scene. Supporters of Prime Minister Botha prevailed and South Africa entered the war as an ally of Britain. But when South African troops invaded the German colony of South West Africa, troops led by General Christiaan R. De Wet rebelled, and some went over to the German side. Despite the rebellion, South West Africa fell to South Africa in 1915. After the war, in 1919, Botha died, and was succeeded by Jan Christiaan Smuts as prime minister.

In the interval between the two world wars, industrialization took place in South Africa at an uncontrollable rate. Whites and blacks alike flocked to the urban areas. No provision had been made for the accommodation or living conditions of the thousands of African workers who streamed into the cities.

A government commission warned that if permanent African communities were allowed to develop in white areas, Africans would soon demand political rights that they could not constitutionally be denied. In 1923, the Natives (Urban Areas) Act was passed, designating Africans living in urban areas as migrants and not entitled to the prerogatives of established citizenship.

African citizenship rights were assigned to areas that the white government had designated as homelands, and pass laws were extended to urban areas where Africans were required to carry proof of employment or permission to seek work with them at all times.

Meanwhile, whites forced off the land by the recession following World War I found expression for their discontent through the Labour Party, which at the time was advocating full employment and state ownership of industry. Many white mine workers in South Africa had experienced union membership in Europe.

Acting as a group, they commanded wages far in excess of those of African workers. The mining industry would much have preferred to employ lower paid African workers in these jobs but nevertheless had in 1918 signed a status quo agreement with the white mine workers that guaranteed that Africans would not be employed in jobs held by whites and vice versa.

In 1920 nearly 40,000 African miners in 22 compounds went on strike to demand an end to the 1918 color bar for higher wages. The Chamber of Mines acceded to some of their demands and began employing Africans in additional work places, in violation of the agreement with the white mine workers.

In 1922, white mine workers went on strike. The government sent in troops, bomber planes, and armored vehicles to put down the strike. In four days of fighting 5,000 miners were arrested, 153 killed, and 500 wounded. The strike was crushed.

Taking advantage of its temporary victory, the government enacted the 1924 Industrial Conciliation Act, which recognized white unions and their right to strike, but effectively prohibited strikes and compelled white unions to settle wage differences at the conference table. Africans and Coloureds were excluded from the legislation because they were not considered “employees.”

Intervention by the government of Jan Christiaan Smuts on behalf of the mine owners so angered white labor that it withdrew its support from the South African Party and joined in a coalition with the pro-Afrikaner Nationalist Party led by Hertzog.

Clements Kadalie, leader of the African Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU), believed that his union’s best interests were with the Hertzog coalition and he persuaded the African National Congress to support the coalition in the 1924 election. The Nationalist-Labour coalition won the election by four seats.

Political Realignment

The coalition which brought together the National and Labour parties formed the Pact government. To the dismay of Kadalie and the ANC, the coalition proceeded to consolidate the movement toward racial discrimination. The objective of racial discrimination was now focused on ensuring white supremacy and Afrikaner interests.

In this period, legislation removed unskilled Africans from jobs with the railroads, harbors, and post offices, and replaced them with unskilled Afrikaners. The white workers received wages far above those paid to the Africans. Between 1924 and 1933 white employment in the railways and harbors increased from 10 percent to almost 40 percent, while African employment declined from 75 percent to 50 percent.

The Mines and Works Act Amendment of 1924 legalized racial discrimination in the mines and signalled to African workers that their hopes of consolidation in the white labor movement were fanciful. Kadalie withdrew from the Labour Party in 1926.

The state intervened in behalf of the Afrikaners in nearly every sphere of economic life: the Customs Act protected domestic industry, land banks made capital available, rates on the railroads favored Afrikaners; the state rewarded them with export bonuses. The state financed their irrigation systems, and set up cooperatives and control boards to develop their local industries.

To expand its electoral base, the government extended the franchise to European women in 1930 and simultaneously set in motion efforts to deprive Africans and Coloureds of their right to vote. In 1936 the Natives Representatives Act removed Africans from the common roll and assigned them a limited form of separate representation. In 1959 the Cape Coloured and Africans were totally disenfranchised with the passage of the Bantu Self-Government Act.

On the international front, Prime Minister Hertzog achieved membership for South Africa in the British Commonwealth. However, by doing so he aroused the fears of the more conservative Afrikaner groups who continued to fear British domination. A splinter group formed under the leadership of Magnus Malan. Hertzog and Smuts then formed a coalition, the United Party.

The outbreak of World War II caused another split in the ruling party. But Smuts and his adherents prevailed, and South Africa entered the war on the side of Great Britain, and in the 1943 election he won a majority, primarily because the opposition was divided.

After the war, however, the different economic sectors vied with one another for an adequate labor force. As a result of the new gold discoveries in the Orange Free State in 1945-46, the mining industry’s labor needs soared and it began to draw as much as 80 percent of its labor supply from Mozambique and Malawi.

In urban areas, manufacturing industries were growing rapidly and required large numbers of unskilled workers. Because the secondary manufacturing industries were willing and able to pay more for labor than the mines, and also because the work was less arduous than on the mines, Africans streamed into the manufacturing areas seeking work.

By 1945, the Natives (Urban Areas) Consolidation Act was enacted to control African workers. The legislation required employers to register every African male employee with a local native advisory board. African women, however, were generally not permitted in urban areas as migrant workers.

The vast influx of Africans who had come to the urban areas in search of jobs could not secure adequate housing facilities because municipal and central governments considered them as migrants and not as a permanent part of the workforce. Shantytowns and slums grew up around urban areas. Both the United Party and the opposition Nationalist Party appointed commissions to investigate and make recommendations on the situation of urban Africans.

The Nationalists’ Sauer Commission report advocated a system of separate development (apartheid) for whites and Africans, with Africans assigned by the white government to so-called “homelands” based on what the whites considered to constitute cultural bases united by a common language.

The concept of separate development appealed to the church-going Afrikaner constituency because it allowed for the removal of unwanted people from their midst and yet permitted the use of African labor at the discretion of the employer. Separate development also permitted white farmers to take over valuable lands farmed by Africans, clearing out the so-called “black spots” from white areas.

In 1948 a coalition of Nationalist and Afrikaner parties, adopting the Sauer Commission recommendations as its party policy, defeated Smuts. The Nationalist Party came to power, and Daniel Malan became prime minister. Under the guidance of Hendrik Verwoerd, who had been a member of the Sauer Commission, and who was later to be prime minister from 1958 to 1966, the government adopted apartheid as its official solution to the “native problem.”

During the more than 40 years of Nationalist rule that followed, there were periods of relaxation of restrictions, usually followed by protest and demonstration, followed in tum by the re-imposition of restrictions.

In 1952, the ANC and the South African Indian Conference (SAIC) staged passive demonstrations that resulted in the imprisonment of nearly 6,000 people. The African protest against the pass laws in 1960 in Sharpeville resulted in the deaths of 69 blacks when police opened fire on a group of demonstrators.

Emergency security regulations that followed outlawed the ANC and the Pan African Congress and almost all other African political organizations, and the imprisonment of their leaders. The government increased military expenditures by 150 percent, imposed more restrictions on black workers and accelerated removal of Africans from rural white areas.

Resistance groups such as the Spear of the Nation, headquartered in Rivonia near Johannesburg, were banned and their leaders went underground. The best known leader was Nelson Mandela, who in 1963 was arrested, tried, and sentenced to life imprisonment. He was not to be released until 1990. Sporadic acts of violence against government facilities continued. By the end of 1966, nearly 4,000 people had been arrested for resistance.

Meanwhile, in 1961, South Africa became a republic. The government’s application for continuing membership in the British Commonwealth was denied because of its racial policies.

In 1966 Verwoerd was assassinated by a deranged white man. Johannes Vorster (q.u.), minister of justice under whom much of the security legislation had been formulated, became prime minister. Repressive legislation continued to be enacted, including the Prohibition of Political Interference Act, the Suppression of Communism Act, the Terrorism Act, and the Public Services Amendment Act. One result of this legislation was the creation of BOSS, the nation’s security police force.

In 1976 riots began in the township of Soweto on the outskirts of Johannesburg, the home of 1.5 million urban African workers, and spread throughout the country. The government again banned all resistance groups, detaining many leaders, among them Steven Biko who died at the hands of police while in detention.

The Vorster government was forced to resign in 1978 because of a scandal involving the misuse of funds. Pieter W. Botha, former minister of defense, became prime minister. His title was changed to president with the adoption of a new constitution in 1984.

In 1985 his government declared a state of emergency following riots in Natal. And in 1987 organized African mine workers staged the largest union walkout in the history of the country. Despite an economic boycott by western nations and years of repression, black South Africans continue to be denied their basic human rights and are forced to live in poverty and fear.

In 1989, Botha was succeeded as president by F.W. de Klerk. Early in 1990, de Klerk lifted the ban on African political organizations, and released Nelson Mandela from prison, where he had been held for 27 years. These events focused worldwide attention on South Africa, and marked the opening of a new phase in the country’s political life.

Among other changes, the tactics and strategies for ending apartheid shifted from the focus on mass mobilization and confrontation of the 1970s and early 1980s to what has been called a “culture of negotiation.”

On March 1 7, 1992 a referendum was held by President de Klerk for the white electorate, which resulted in a mandate to continue with his reform program and to negotiate a new constitution with the ANC and other organizations.

After a lengthy period of talks involving more than 400 fora at various levels around the country, delegates representing 21 political parties and groupings entered into 11 months of arduous “democracy talks” in early 1993 that culminated in an announcement on November 17, 1993 of agreement on a draft interim constitution and confirmation of an earlier announcement that April 27, 1994 would be the date of the country’s first all-race election. White rule formally ended on December 7, 1993 with the inauguration of a multiracial 32-member Transitional Executive Council.

The TEC was charged with serving as a watchdog over the National Party government and ensuring that no party enjoyed an advantage over another in the run-up to the election.