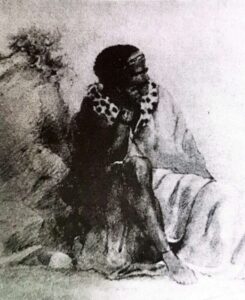

MAQOMA

- 6 Min Read

Maqoma (1796 – September 9, 1873), who figured prominently in the frontier history of Cape Colony, is reputed to have been the most intelligent of all the Xhosa Rarabe chiefs. In 1834 he led the largest Xhosa invasion of eastern Cape Colony in what was to prove an unsuccessful attempt to hold back white settlement on Xhosa lands.

PHOTO CAPTION: Maqoma. SOURCE: EA Library

Born in what is now the Middeldrif district of the Ciskel, he was the eldest son of Ngqika, paramount chief of the Rarabe Xhosa. His mother, Notonta, was however a junior wife, which barred Maqoma from succeeding his father. In 1817 he was present during the negotiations between Ngqika and Lord Charles Somerset, governor of Cape Colony, on the Kat River. The following year, in one of the periodic wars that broke out between Ndlambe and Nggika, Maqoma distinguished himself by repeatedly storming the enemy lines, despite his wounds.

In 1819 Somerset obliged Ngqika to give up land between the Kei and Keiskamma Rivers, which was then designated as “neutral territory,” to form a buffer zone between the Xhosa and the Afrikaner settlers. Opposing this settlement, Maqoma settled in Winterberg in the “neutral zone” in 1821, from where he and his followers launched cattle raids against the Boer settlers. To check such raids the Cape authorities built Fort Beaufort on the Kat River in 1822.

As a result of further losses of cattle, a Boer commando attacked Maqoma’s kraals in 1823, seizing 7,000 cattle. After this a degree of peace was established between the Xhosa and the Boers, and some 5,000 of Maqoma’s cattle were returned. The settlement, however, proved only temporary. During the Mfecane raids of 1827-28, Maqoma and his people played no significant role. Following a large cattle raid against the Thembu, which he launched in 1829, however, a force from Cape Colony drove him and his people from their land, obliging them to settle east of the Kabusi River. The lands they had left were then assigned to Khoi Khoi and Griqua settlements.

Later in 1829, on the death of his father, Ngqika, Magoma’s half-brother Sandile, was named his successor. As he was still only nine years old, however, Magoma, two of his brothers, and Sandile’s mother were named as regents. Maqoma soon became the most powerful and influential of the regents. The years that followed were marked by rising tension, with the Rarabe Xhosa harbouring resentment over their expropriation and treatment by the Cape administration. Maqoma was aware, too, that Boer commandos often “recovered” more cattle from his people than they had lost.

On several occasions, he told missionaries that the burden of his complaint almost exclusively concerned the loss of his land, of the wrong done by the treaty of 1819, and of misunderstandings caused by faulty or corrupt interpreters. Maqoma appealed to the missionaries to help them recover their land by representing their grievances to the government but they declined, saying they did not wish to interfere.

In December 1834, following a severe drought that led to pressure on the Rarabe lands, Maqoma, backed also by the Galeka Xhosa, attacked Cape Colony in what became known as the Sixth Frontier War. Before attacking, the Xhosa emphasised that they did not seek a fight to the death, but a negotiated agreement, especially one that would return to them their confiscated lands east of the Fish River.

The Xhosa then swept into Cape Colony, leaving a trail of destruction from Somerset East down to Algoa Bay. After two weeks, however, the invaders were checked and, in the months that followed, defeated. Peace was made in September 1835. By its terms, the entire Ciskei, from the Keiskamma, was declared British territory and named the Queen Adelaide Province; 17,000 Mfengu (refugees from the Mfecane) were settled in the Ciskei near the newly-established Fort Peddie, to act as a buffer between the Xhosa and the Cape Colony; and the Xhosa were declared to be British subjects.

These arrangements, however, for which the governor of Cape Colony, Benjamin D’Urban, was primarily responsible, were short-lived. In a letter written in 1835, but received in 1836, the British colonial secretary demanded that the Ciskei be returned to the Xhosa. In May 1836 Queen Adelaide Province was declared independent, and Mgoma was again recognised as a chief by the Cape authorities. The four years that followed were marked by shifts in British policy, although Magoma was generally treated with leniency. It was at a conference with the Cape authorities held in these years that Magoma declared, “The white man conquers only to dispossess. Our people steal oxen and cows but the government steals with the pen.”

In 1840 Sandile came of age and became paramount chief of the Rarabe Xhosa, after which Magoma’s influence began to decline. When the Seventh Frontier War broke out in 1846, he became the first Xhosa chief to sue for peace, surrendering in December. When peace was declared the following year, the Cape governor, Sir Harry Smith, annexed the entire Ciskei, which was named British Kaffraria.

During the Eighth Frontier War of 1850-53, Maqoma again defied the British, strongly supported the prophet Manjeni, and became the principal Xhosa commander. When the Xhosa chiefs sued for peace in 1853, it was Magoma who conducted the resulting negotiations with the Cape governor, George Cathcart. Again Maqoma and his people were moved eastward across the Kabusi River. Cathcart’s successor as Cape governor, Sir George Grey, placed a magistrate alongside every chief.

Another Xhosa prophet, however, Mhlakaza arose in 1856, inciting the Xhosa to slaughter their cattle. Magoma strongly advised Sandile to support the prophet. The slaughter took place in 1856-57, and famine and looting followed. Magoma was arrested by the British and accused of having been a party to the murder of a chief who had refused to kill his cattle. In December 1857 he was sent into exile on Robben Island, in Table Bay. Although he was sentenced to spend 21 years there, he was permitted to return to the mainland in 1869. Again accused of incitement to violence, he was returned to Robben Island, where he died in 1873.

ENOCH W.D. DUMA