SCOTT, MICHAEL

- 4 Min Read

The Rev. Guthrie Michael Scott (Sussex, England, July 30, 1907-London, September 14, 1983) was an Anglican clergyman and passive resister. He was the first petitioner to appear before the United Nations, and the first to bring the question of the status of South West Africa (now Namibia) to international attention. He was the single individual most responsible for focusing attention on the issue of apartheid in South Africa, and for bringing that policy into disrepute.

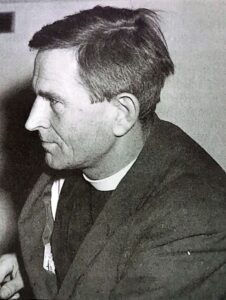

PHOTO CAPTION: Scott Michael. SOURCE: EA Library

The son and grandson of Anglican clergymen, he was raised in a poor parish near the Southampton docks in England. Scott was educated first at King’s College, Taunton, England, and then–after he had contracted tuberculosis and was sent to South Africa for his health–at Grahamstown, South Africa. In l930, he was ordained a clergyman, and served as curate in a parish in Sussex. He was next sent to South Kensington, London. There, during the hunger marches of the Great Depression, he experienced Fascism as espoused by Sir Oswald Moseley and became attracted to Communism, but was disillusioned by the Nazi-Soviet pact of 1939.

Moving to India, Scott served as chaplain first to the Bishop of Bombay from 1935-37, and then at St. Paul’s Cathedral, Calcutta, from 1937-38. While there, he learned to fly. He also acted as a courier for the Communists, until he broke with them in 1939. He was strongly influenced by Gandhi and by one of his disciples, C. F. Andrews.

Back in Britain, at the outbreak of World War II, he studied the philosophy of non-violence. Scott joined the R. A. F., and, despite his pacifism, was trained as a rear-gunner. In 1941, for health reasons he was advised to return to South Africa. He was to be dogged by Gohn’s disease all his life.

From 1943-46, he was chaplain to an orphan age in Johannesburg, South Africa. In 1946, he heard that Indians, dispossessed of their lands were engaging in non-violent protests in a township called Tobruk in the Durban area, where they were regularly roughed up by white youths. Witnessing this, Scott joined the protestors, and was arrested by the police for creating a disturbance: he was sentenced to three months imprisonment, thus becoming the first white man to be jailed for opposing apartheid.

On his release, Scott traveled to South West Africa and met with Khama the Great, at the request of Tshekedi Khama. Khama asked him to publicize the case for independence of the Herero people of South West Africa. Funded by contributions from the Herero people, he travelled to London, where he began a close association with the Society of Friends (Quakers), establishing his headquarters at the Quaker International Center in Tavistock Square, London, and founding an organization called the Africa Bureau.

He then travelled to New York, where, after considerable opposition, the United Nations agreed to hear Scott’s petition from the Herero chief on behalf of his people. This made him the first person the U. N. agreed to hear as a petitioner. In his struggle to be heard, Scott was backed by the delegation of India and by the New York-based International League for the Rights of Man.

He was to return to New York to press the case of South West Africa every year for the next 36 years, and undoubtedly succeeded in thwarting South Africa’s drive to absorb the territory as a part of South Africa – instead of being recognized (as it was) as a United Nations Trust Territory.

Although without success, he appeared three times before the International Court of Justice at The Hague on behalf of South West Africa; in doing so, he helped lay the foundations for Namibia’s future independence. After he left South Africa in 1947, he was declared an Anglican clergyman and forbidden to return.

In 1958, he wrote his autobiography, entitled A Time to Speak. Scott was active in helping Tshekedi Khama and supporting the movement to permit the Kabaka to return to Uganda. In later years, he also supported the Naga people of India in their struggle for justice. From 1948 onwards, Scott’s causes were aided by the moral support of David Astor, owner of the influential weekly, the London Observer.

In later years, he formed a friendship with the philosopher Bertrand Russell, with whom he founded the Committee of One Hundred, which launched a campaign for nuclear disarmament.

A tall, gaunt, and notably eccentric man, Scott generated a remarkable spiritual and moral force that was recognized by all who met him. An intense and often tortured individual, he was characteristically gentle in manner. A controversial figure, he attracted many friends, and also made influential enemies.

KEITH IRVINE