Ethiopia

- 75 Min Read

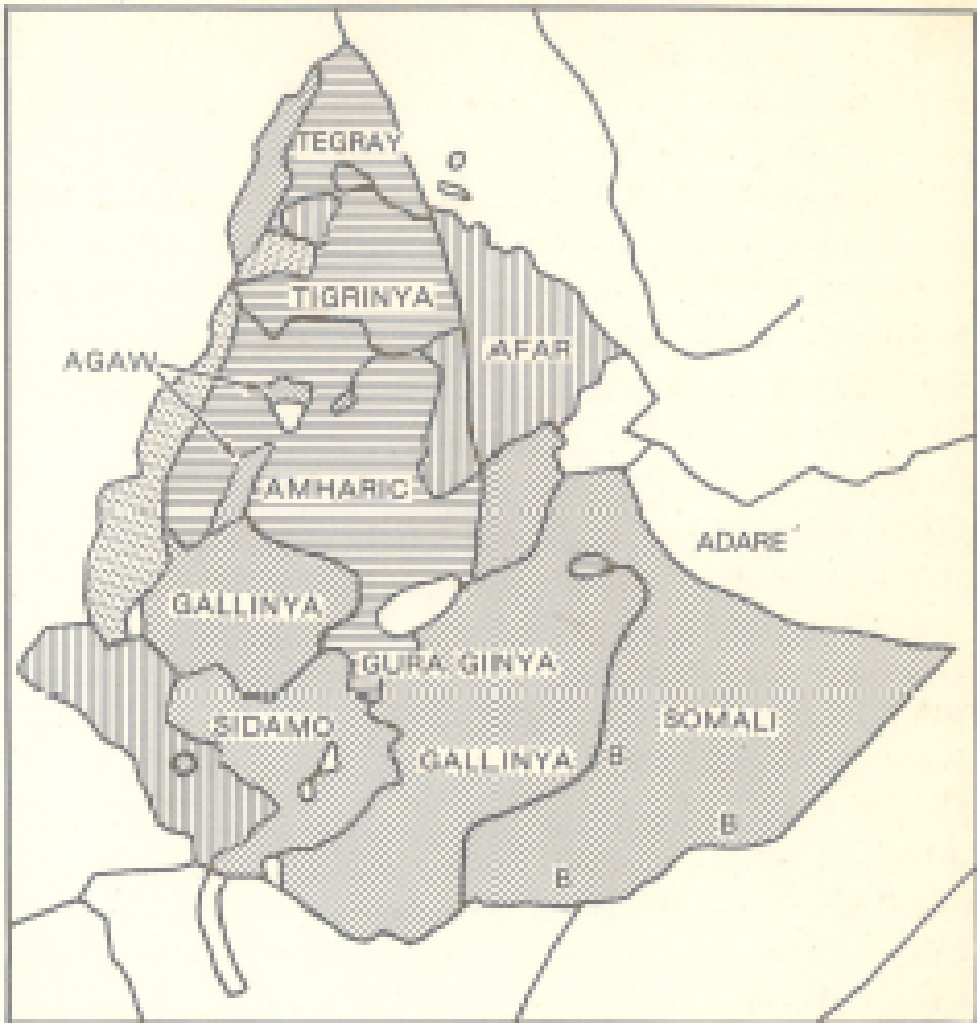

PHOTO CAPTION: The Map of Ethiopia. SOURCE: EA Library

by Richard Pankhurst

Our earliest glimpses of Ethiopia’s history go back over three millennia. The Pharaohs of ancient Egypt, as is known from their inscriptions, used to send expeditions to the southern Red Sea and Gulf of Aden area to seek incense, spices, ivory, and gold.

These valuable products, most of which must have originated in what is now the Ethiopia and Somalia region, are described as having been obtained from the Land of Punt, though the exact geographic location of this territory is by no means clearly established. It would appear safe, however, to assume that that land, and a greater· part of present-day Ethiopia, were occupied by Cushitic peoples. A millennium or so later, perhaps between the 7th and 3rd centuries BC, migrations of Semitic peoples from southern Arabia to the Horn of Africa are believed to have occurred. The South Arabian immigrants, who were destined to become the dominant group in this region of Africa, brought with them their language, culture, and forms and ideas of government. The advent of the South Arabian language is of particular significance to the historian since its alphabet, which was related to the Phoenician, was used in the first historical inscriptions produced by the inhabitants of this area.

THE KINGDOM OF AKSUM

The Semitic immigrants from South Arabia and the local Cushitic inhabitants intermarried, thereby leading to a blending of races in the region, now constituting the northeastern provinces of Ethiopia. Around this period, or somewhat later, there emerged a new culture and civilization which had its roots in both Semitic Arabia and Cushitic Africa, and which is now called Aksumite (Axumite), after its capital, Aksum (Axum). The Aksumites practised a comparatively advanced form of agriculture, traded widely with the countries of the Middle East and India, and proved themselves excellent architects and builders in stone. They produced the famous monolithic stelae (obelisks) of Aksum, various imposing buildings, and coins of gold, silver, and bronze, which circulated for at least 700 years. During this period a new language called Ge’ez, also referred to as Ethiopic, evolved. Ge’ez, in which the Aksumites carved most of their inscriptions, owed much to the old South Arabian language, but was also greatly influenced by the Cushitic languages spoken by the inhabitants of the region. The Ge’ez script was likewise derived from the South Arabian but differed substantially from it. The South Arabian script, like that of most Semitic languages, had made little or no use of vowels and was often written from right to left, though on other occasions it was used in what is termed the “boustrophedon” or ploughwise manner, whereby the first line is written from right to left, the second from left to right, the third from right to left, etc. The Ge’ez script also differed from the South Arabian in that the vowel signs were incorporated in each letter so that each character represented a syllable. Another innovation of the Ge’ez script was that, unlike the South Arabian, it was written from left to right.

Ge’ez, which has retained its influence to the present day, has aptly been termed the Latin of Ethiopia. Considered by many authorities as the root of an entire family of Semitic languages of Ethiopia, it is still the liturgical language of Ethiopian Christianity, and has contributed the basic characters in which virtually all Ethiopian languages are written. Semitic languages are spoken in the greater part of what is now northwest Ethiopia. They include Tigrinya (Tigrina), which is fairly closely related to Ge’ez, and is spoken in the highlands of Eritrea and throughout Tegre province, where the ancient capital, Aksum, is situated, and Amharic (Amarina), the official language of the modem state, employed in government business, the schools, and almost all contemporary literature. Other Semitic languages are Tegray, the closest to Ge’ez, which is used in parts of Eritrea, Adare (also known as Harari), spoken in the walled city of Harar in the east, and the Gurage dialects, which are employed south of Addis Ababa. Cushitic languages are, on the other hand, dominant throughout most of the remainder of· the country. Afan Oromo, or Gallinya, because of the northward migration of the Oromo or Galla people in the 16th and 17th centuries, is spoken in the greater part of the west, south, and east. Afar, or Danakil, is spoken in the northeast, and Somali in the southwest, and Nilotic, or Sudanic, along the Sudan frontier in the west.

The Aksumite empire seems to have reached its zenith several centuries after the birth of Christ. In the 4th century, King Ezana (Aeizanas) erected a number of inscriptions to record his successful expeditions. While in the 6th century King Kaleb [circa 514-543] despatched an army to occupy a part of south· Arabia, which was temporarily brought under Aksumite control.

THE COMING OF CHRISTIANITY

One of the most important events of this period was the official conversion of the Aksumite state to Christianity, a religion which by then was beginning to penetrate into both northeast Africa and Arabia. This conversion followed the shipwreck in the early 4th century of a young Syrian Christian called Frumentius, who imparted his faith to the then king of Aksum.

PHOTO CAPTION: A panoramic view of the Holy City of Aksum. SOURCE: EA Library

The conversion took place during the reign of Ezana, who came to the throne between 320 and 325. Ezana’s early coins and inscriptions suggest that he was originally pagan, while his later coins bear the effigy of the Cross, and his last inscription closes with an invocation to the “Lord of Heaven.”

In the following centuries, the Bible and other Christian texts were translated into Ge’ez, and numerous churches were built, some of the most remarkable by excavating the living rock. The tradition of such church-building was to continue for many centuries.

During the reign of King Armah, early in the 7th century, the Aksumite state gave asylum to a hundred of, the early followers of the Prophet Muhammad (circa 570-632), including two of Muhammad’s future wives, Umm Habibah, and Sowdah, the widow of Sokran. The founder of Islam is said to have shown his gratitude by commanding his followers ”to leave the Abyssinians in peace,’ ‘ thereby exempting them from the jihad, or Holy War. Relations between Christian Aksum and Muslim Arabia were, however, later to deteriorate. The rise of Islam was a turning point in the history of Ethiopia. The Arabs, encouraged by the new religion, gained control of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, thus contributing to the decline and fall of the Christian Aksumite state. The 18th-century British historian Edward Gibbon (1737-94), recalling this development, wrote in an oft-quoted half-truth: “Encompassed on all sides by the enemies of their religion, the Aethiopians slept near a thousand years, forgetful of the world by whom they were forgotten.”

Christian Ethiopia, it should be emphasized, in fact never really forgot the outside world, for Ethiopian pilgrims regularly travelled, mainly by way of the Egyptian desert, to Jerusalem. Sultan Salah ad-Din (1137-93) granted the Ethiopians a chapel in the Holy Sepulcher as well as a station in the grotto of the Nativity in Bethlehem. Foreign, contacts are also revealed in E. Renaudot’s Historia Patriarch Forum Alexandrinorum (“History of the Alexandrian Patriarchs”) [1717], which tells of a king of Ethiopia writing to a king of Christian Nubia to inform him of a woman, later traditionally referred to as Judith, (Gudit), who had risen up and was destroying the churches, killing Christians and devastating the country. This period of difficulty for the Christians was one of opportunity for the Muslims. Islam now made rapid inroads and spread from such coastal centres as Sawakin (Suakin), Badi, Dahlak, Zayla, and Barbara (Berbera) to much of the interior. The new religion was embraced by many of the Beja people in the north, virtually all the Afars and Somalis in the east, and a significant proportion of the Sidama in the south. A number of Muslim sultanates came into existence in the east of the country, the most important of which were Hadeya, Fatajar, lfat, Dawaro, Bali, and Mara.

After the fall of the Aksumite kingdom, a new dynasty called the Zagwe (Zague) established itself further south in the mountains of Lasta, where it made the town of Roha its capital. The Zagwe, who assumed power around 1137, were subsequently condemned as usurpers, but are believed to have been able rulers, and the period of their dynasty witnessed important religious and cultural activity. This included the excavation of the famous rock-hewn churches at Roha, which was renamed Lalibala (Lalibela), after Lalibala [late 12th-early 13th centuries], the best known member of the dynasty. These finely proportioned and decorated churches which were in the long-established tradition of Ethiopian rock churches, have been reputed among the wonders of the world. The Zagwe dynasty is said to have ended in 1270, when the last of the line, Naakuto Laab, described as a just and peaceable king, agreed to a request by a religious leader of-· Shawa, Abuna Takla Haymanot, that he should abdicate in favour of Yekuno Amlak [ruled 1270-85], a prince of Shawa.

Yekuno Amlak, who established his capital at Tegulat in Shawa, is reputed to have claimed descent from the Biblical King Solomon (King of Israel in the 10th century BC), and, the Queen of Sheba (Saba’), known in Ethiopia as Makeda, who is variously believed to have lived in what is now northern Ethiopia, or else in southwest Arabia. This, as far as is known, was the first time that such august lineage was ever claimed by a ruler of Ethiopia. An agreement then concluded is supposed to have laid down among other things that the Ahuna, or head of the Ethiopian church, should thenceforth be appointed by the Patriarch of the Church of Alexandria. Indeed, not until the 20th century was an Ethiopian, rather than an Egyptian, appointed Abuna.

The establishment, or, as some have claimed, “restoration” of the Solomonian line, was followed by a major period of consolidation. Emperor Amda Tseyon [ruled 1312-42] extended his dominions to the northwest to embrace Gojam and Bagemder, and to the southeast to subjugate the Muslim sultanates of Adal, Ifat, and Hadeya, while the subsequent Emperor Zarea Ya’ eqob [ruled 1434-68] devoted much of his efforts to administrative re-organisation and the establishment of religious orthodoxy. Such events were accompanied by a significant literary revival, perhaps attributable to the increased power and wealth of the church, the principal patron of the arts. Many Ge’ez writings were produced, notable among them being the Kebra Nagast, or “Glory of Kings,” which embodied the claim of the royal house to Solomonic descent, and the Fetha Nagast, or “Law of the Kings,” the country’s legal code which proclaimed the divine right of kings on a scriptural basis.

THE MUSLIM INVASION

The power of the mediaeval Ethiopian state was challenged in the early 16th century when an Ethiopian Muslim from the east of the country, Ahmad Ibn Ibrahim [1506-43], nicknamed Gran, or the “left-handed,” captured and held the great Muslim city of Harar, refused to pay taxes to Emperor Lebna Dengel [ruled 1508-40] in 1527, and embarked, in 1529, on a Holy War against Christian Ethiopia. Aided by the Ottoman Turks, and making good use of fire-arms, which were then beginning to be imported into the area, he succeeded between 1531 and 1535 in overrunning most of the Ethiopian empire as far as Gojam in the west and Tegre in the north. He burned and looted many churches and monasteries, and forced numerous Christians to become Muslims. The great Muslim conqueror was, however, finally defeated and killed in 1543, largely because of the intervention of a Portuguese force led by Ch_ristovao da Gama (1517-52), who had arrived at the Emperor’s request. Gran’s death was rapidly followed by the collapse of Muslim power and the restoration of imperial rule under Emperor Galawdewos [ruled 1540-59].

The weakening of both the Christian empire and the Muslim sultanates resulting from Gran’s wars may have contributed to the expansion of the Oromo, or Galla, who were then a pastoral people. The Oromo, perhaps on account of Somali and other pressures, swept northwards into what is now central, western, eastern, and even a part of northern Ethiopia. The Oromo thus greatly reduced the territories subject to both the Christian emperors and the Muslim amirs of Harar. The Turks meanwhile had occupied the port of Massawa in 1557, thereby restricting the empire’s access to the coast. Though Emperor Sartsa Dengel [ruled 1550-97] succeeded in strengthening the empire, his successors could scarcely withstand Oromo and Turkish pressures. Often on the defensive, they began to hope for renewed help from Portugal. Encouraged in this by Portuguese and Spanish Jesuits, who had first arrived in 1557, two emperors, Za Dengel (ruled 1603-04) and Susneyos [ruled 1607-32], embraced the Roman Catholic faith. Susneyos tried to convert Ethiopia to Catholicism by force.

PHOTO CAPTION: A view of Gondar, in northwestern Ethiopia, Gondar was the capital of Ethiopia from about 1630 to about 1860, and contains the remains of many palaces and other royal buildings, and churches. SOURCE: EA Library

Orders were given for the re-ordaining of priests, the re-consecration of churches, the re-baptizing of people, and for revisions of festivals and fasts. These attempted changes led to intense popular opposition and many rebellions. Susneyos was obliged, in 1632, to restore the old Ethiopian Orthodox faith, after which he abdicated in favour of his son Fasilidas [ruled 1632-67], who banished the hated Jesuits from Ethiopia in 1634. Contacts with Ethiopian Christendom were suspended, though attempts were made to replace them with relations with other powers, notably the Sultanate of Turkey, and the Mughal (Mogul) emperor of India, Aurangzeb (reigned 1658-1707).

The period of greater isolation following the expulsion of the Jesuits witnessed the establishment, in 1636, of the city of Gondar, north of Lake Tana. This was a development of considerable significance, since the country had been mainly governed since the time of Yekuno Amlak, from moving capitals in the form of military camps. Fasilidas and other emperors who followed him built a series of castles at Gondar, which emerged as the empire’s sole urban centre, as a fine imperial city, and as a major centre of commerce and culture with more than 40 churches and many church schools.

THE TIME OF THE MASAFENT

Gondar reached its heyday during the reign of Emperor Iyasu I [reigned 1682-1706], who conducted several successful expeditions and re-organised the taxes. After his deposition and murder, however, imperial power began rapidly to decline. Though the Christian Church gave the empire an element of religious and cultural unity, the various provinces, each ruled by its own feudal lord, reasserted their authority, and there were frequent civil wars. A pretence of unity was nevertheless maintained, for the various cheiftains still paid nominal allegiance to an emperor of Goodar who was, however, usually a puppet of one or other of the great lords. One of the most important of these, Ras Mikael Sehul of Tegre, took advantage of his province’s near monopoly of firearms to make himself the master of Goodar. This period was later referred to by Ethiopian historians as the era of the masafent, or judges, an allusion to the time recorded in the Biblical Book of Judges when: “There was no king in Israel: every man did that which was right in his eyes.” The 19th century thus dawned on a divided country in which there was no central authority. The highlands, once the site of the Christian empire, were divided into three independent states: Tegre – whose best-known chiefs were Ras Walda Selasse [ruled 1780-1816], Dajazmach Sabagadis, and later Dajazmach Webe [ruled 1831-55]; Amhara, with Goodar as its capital, one of whose principal governors was Ras Ali, representative of the Galla dynasty of Yaju; and Shawa, which was ruled for a time by King Sahla Selasse [ruled 1813-47], whose grandson was later to become Emperor Menilek II [ruled 1889-1913].

Harar was a separate amirate, and a centre of Islamic culture, which issued its own currency, and whose merchants, many of whom went on pilgrimages to Mecca, travelled as far as Egypt and India. In the southwest, mainly inhabited by people practicing traditional religions, the states of Kaffa, Janjero, Guma, Goma, Enaryea, Gera, and Jimma had also come into existence. One of the most remarkable, and still inadequately explained, features of this period was the rise of a number of Oromo monarchies, the most important being those of Enaryea, and Jimma Kaka, where the old egalitarian Gada system, based on rule by rotating age groups, was challenged by rich and powerful military leaders who, possibly because of their possession of fire-arms, established their own dynasties. Such rulers, some of whom displayed great statecraft, included Ibsa, better known as Abba Bagibo, who reigned in Enaryea from 1825-61, and Abba Jifar Sana, who ruled Jimma Kaka from 1830-55, adopted Islam in 1830, and developed institutions of government which were to endure into the early 20th century.

TEWODROS II

In the Christian highlands, memories of a great and glorious past still remained, and cultural contacts, largely through the Church, were preserved. Indeed, recognition of the ·country’s former greatness and unity provides the background for the rise of Emperor Tewodros II [reigned 1855-68], regarded by many as the protagonist of modern Ethiopia.

PHOTO CAPTION: The Queen of the Galla country, with her youngest son, and a Muslim priest. SOURCE: EA Library

Tewodros, originally known as Kassa, began his career as a freelance soldier in the western frontier district of Qwara. His bravery won him the admiration of his troops, and he was so successful that Empress Manan, mother of Ras Ali, the ruler of Goodar, arranged for him to marry the latter’s daughter.

Kassa, however, soon rebelled, captured the empress, and defeated both Ras Ali and Dajazmach Webe, as well as other provincial rulers. In 1855 he proclaimed himself emperor and adopted the name Tewodros – a significant appellation, for a legend, then widely believed, prophesied that a monarch of that name would appear who would rule justly, eradicate Islam, and capture Jerusalem.

Tewodros, a charismatic if at times over-excitable leader, did much to justify his name, for he proved a notable unifier, innovator, and reformer. In a series of brilliant campaigns, he succeeded in occupying all the provinces – Tegre, Gojam, Wallo, and Shawa, as well as Bagemder. Realizing _that he could gain and keep control of the country only by military means, he devoted much of his attention to reorganizing the army. He sought to replace the old unpaid levies, who ravaged the countryside in search of food without being very effective on the battlefield, with a well-equipped army of professional soldiers, and attempted to have cannons and mortars cast for him by Protestant missionaries and others at his court. He also sought to achieve various other reforms, including the curtailment of church land and the overthrow of the old provincial nobility. Opposition from the latter, supported, it would appear, by the clergy, led, however, to the decline of his power.

Tewodros’s desire to open relations with European Christendom, and above all to obtain gunsmiths and other craftsmen from abroad, caused him, after earlier rebuffs from the British, to write in 1862 to Queen Victoria (ruled 1837-1901), but the British government, being unwilling to help, left his letter unanswered. Tewodros, angered by this slight, as well as by other indications of British disfavor, imprisoned the queen’s envoy and other foreigners. The British government at first agreed to recruit the craftsmen Tewodros wanted, but, infuriated by his continued detention of British prisoners, and aware of his declining strength, soon afterwards decided to use force against him. An ‘ Anglo-Indian force, led by Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Napier [1810-90], was. accordingly, dispatched against him in 1867. Tewodros fought the invader in the vicinity of his mountain fortress of Magdala.

Defeated by the superior firepower of the enemy, he released his captives, but the British, apparently intent on seizing him, rejected his peace overtures. Realizing that further resistance would be vain, and unwilling to fall into the hands of his foes, he committed suicide on April 13, 1868.

YOHANNES IV

The death of Tewodros left the empire once more divided and without any single ruler. Two important personalities, however, soon took the stage: Sahla Selasse’s grandson Menilek, whom Tewodros imprisoned, but who had earlier escaped to claim the throne of Shawa; and Kassa, a chieftain of Tegre who had allowed Napier’s army to pass through his domains, and had been rewarded for his collaboration with a significant gift of British arms. Kassa defeated his main rival in the north, Ras Gobaze, who had assumed the title of Emperor Takla Giyorgis[ruled 1868-71], and was himself shortly afterwards crowned, in 1872, as Emperor Yohannes IV [ruled 1872-89]. More conservative than Tewodros, he retained most of the old provincial rulers and declared himself a friend of the church. By such a conciliatory policy, he succeeded in bringing the greater part of northern Ethiopia under his rule, and thus achieved a greater measure of effective unification than his predecessor. Confronted with encroachments from the Egyptians, he rallied the Christian population against the Muslim foe. The latter was exceedingly well armed, and had the assistance of European and American officers, but was roundly defeated in two major battles, at Gundet in 1875 and at Gure in 1876, where Yohannes captured more than 25 cannon and more than 15,000 modem rifles as well as much ammunition. After these signal victories he turned his attention to Menilek, who had been claiming the title of emperor, and, so far from assisting in the war with the Egyptians, had actually been corresponding with them in friendly terms. Yohannes marched into Shawa in 187S, and a clash of arms between him and Menilek seemed imminent. Anxious to avoid a confrontation, which might have led to heavy casualties and a weakening of their position vis-a-vis their Muslim neighbours, the two rulers agreed to a compromise peace.

Menilek renounced the title of emperor in favour of that of King of Shawa, while Yohannes recognized Menilek’s full independence, subject to the payment of a modest tribute, agreed to crown Menilek as King of Shawa and Wallo, and also agreed to allow the latter’s descendants to succeed him to this title. On the basis of this accord Yohannes duly crowned Menilek, and soon afterwards agreed with him that. steps should be taken to convert the Muslim and animist population, mainly in Wallo, to Christianity. A dynastic marriage was later arranged, in 1882, between the emperor’s son Ras Araya Sellase and Menilek’s daughter Zawditu [who later reigned from 1916-30], then aged 12 and 7 respectively. Important international developments were meanwhile taking place. In 1869 an Italian priest named Guiseppe Sapeto [1811-95], acting on behalf of a private Italian firm, the Rubattino Shipping Company, had purchased the port of Assab from the local chief, and in 1882 the port was declared an Italian colony. At about the same time discontent in Egypt, largely engendered by the failure of the campaigns against Ethiopia in 187 5-76, led to the revolt of an Egyptian arms officer, Arabi (‘Urabi) Pasha (Colonel Arabi) [1839-1911], who had himself been present at the Egyptian debacle in Ethiopia. The revolt was followed in 1882 by the British occupation of Egypt – a turning point in African history.

Meanwhile, in the Sudan, the Mahdi(Al-Mahdl), Muhammad Ahmad (1844-85), had begun a revolution that was so successful that the British government decided that Egyptian and British troops would have to be evacuated from the Sudan. The help of Emperor Yohannes in this withdrawal was requested, and a treaty was signed with him in 1884, one provision of which laid down that there would be free transit “under British protection” for Ethiopian goods, including munitions of war, through the ·port of Massawa. The value of this agreement for Ethiopia was, however, limited, for on February 3, 1885, the Italians seized Massawa, with the consent of Britain, which favoured Italian expansion in the hope of curbing that of France.

The occupation of Massawa may be said to have effectively opened the era of the European “Scramble for Africa” in this part of the continent. The Italians, who had no intention of restricting their interest to the port, soon advanced inland but were ignominiously defeated by Alula Qubi at Dogali, in the coastal lowlands, in January 1887. Faced with the likelihood of war between Italy and Emperor Yohannes, the British dispatched an envoy to the latter·, proposing that he should agree to an Italian occupation of the coastal strip. The monarch refused, however, protesting that if Queen Victoria wished to make peace it should be done when the Italians were in their country and the Ethiopians in theirs. Faced with the threat from Italy, he strengthened his defences by transferring a garrison from Galabat on the Sudan frontier. Finding the border unguarded, the Dervishes, or followers of the Mahdi, broke in at that point. Yohannes hastened to Galabat to repel them, but at the close of a victorious battle, in March 1889, was mortally wounded by a sniper’s bullet. With his death, the highly personalized government he had established collapsed, and Menilek was able to reassert his claim to the imperial throne.

MENILEK II

Menilek, who may justly be termed the founder of modern Ethiopia, continued the work of reunification begun by Tewodros and Yohannes by systematically conquering or otherwise reducing to subjection all the provinces of the south. Parts of Gurage, south of Shawa, had been occupied as early as 1875, and in 1881 an expedition had been dispatched to Kaffa in the southwest, with Jimma, Gera, and Guma agreeing to pay tribute the same year.

A first expedition was sent to Arusi, further south of Shawa, in 1882. Walaga was seized, and the ·annexation of Arusi was completed in 1886. The old city state of Harar, to the east, fell to Menilek’s guns in 1887, and Illubabor in the southwest was occupied in the same year. The acquisition of Gurage was completed, and Kanta and Kulla were annexed in 1889. The occupation of Kambata, begun in 1890, was completed in 1893. Ogaden, east of Harar in the Horn of Africa, as well as Bale and Sidamo, both to the south of Arusi, were occupied in 1891, and Gofa in 1894, in which year · Walamo was also conquered. One of Menilek’s main preoccupations throughout this time was with importing fire-arms. He was more successful in this quest than previous rulers of Ethiopia in that the Italians in Eritrea and the French in their Somali Protectorate were both, for reasons of their own, in favour of supplying him with arms. The Italians, before the death of Emperor Yohannes in 1889, had hoped to win the Sha wan ruler’s friendship, or at least neutrality, in their conflict with Yohannes, while the French were anxious to obtain Menilek’s cooperation in their rivalry with Britain.

Italian Interest in Ethiopia

The “Scramble for Africa,” it should be emphasized, was by then in its heyday. Only a few years earlier, in 1885, the principal European powers had met in Berlin and, to avoid disputes among themselves had devised the General Act of Berlin. Article 34, which was destined to be significant in Ethiopian history, declared that: Any power which henceforth takes possession of a tract of land on the coast of the African Continent outside its present possessions, or which, being hitherto without possessions, shall acquire them, as well as the power which assumes a protectorate there, shall accompany the respective act with a notification thereof, addressed to the other Signatory Powers ….in order to enable them, if need be, to make good any claims of their own.

PHOTO CAPTION: Menilek II with his chosen heir, Lej Iyasu Mikael. SOURCE: EA Library

Menilek’s foreign policy at this time centred largely on cooperation with Italy, from which he obtained much of his arms, as well as several physicians, for the Italians hoped, as we have seen, that he could help them ·against Yohannes. The latter’s unexpected death, in March 1889, radically changed the basis of Menilek’s relations with Italy, for there was no longer any major enemy in northern Ethiopia against whom the latter country needed an ally. Relations between Menilek and Italy nevertheless continued to be of crucial importance. On May 2 less than two months after the demise of Yohannes – he signed a Treaty of Perpetual Peace and Friendship with Italy.

The agreement, which was concluded at Wechale, a village in Wallo, contained articles of benefit to both signatories. The pact served the interest of the Italians, in that Menilik agreed to recognize their sovereignty over the northern plateau, including the town of Asmara in what is now Eritrea which Yohannes, as the ruler primarily of Tegre, would almost certainly never have tolerated. The accord, on the other hand, was also of advantage to Menilek, for Italy recognized him as emperor, thus becoming the first foreign power to do so. Another article of great interest to him specified that he was entitled to import arms and ammunition through Italian territory – no small consideration, because the previous year the British had persuaded both France and Italy to agree that arms should be allowed into Ethiopia only in limited quantities and under license.

The most famous article of the Wechale treaty was, however, Article 17, which was soon the basis of a major dispute. The quarrel arose from the fact that the treaty had two texts, one in Amharic and the other in Italian, the sense of which, though elsewhere identical, ·differed materially in this article. The Amharic stated that Menilek should have the power to avail himself of the Italian authorities for all communications he might wish to have with other powers. The Italian text, on the other hand, made this obligatory.

The Italians, after occupying the northern plateau, where they carved out their colony of Eritrea in 1890, informed the European powers that “in conformity with Article 34 of the General Act of Berlin” Italy served notice that “under Article 17 of the perpetual treaty between Italy and Ethiopia. it is provided that His Majesty the King of Ethiopia consents to avail himself of the Government of His Majesty the King of Italy for the conduct of all matters that he may have with other Powers or Governments.” On these grounds, the Italian government claimed to have established a protectorate over Ethiopia, and this was duly recognized in Europe where cartographers began indicating Ethiopia on their maps as “Italian Abyssinia, ” while Britain, the principal colonial power in the area, entered into protocols with Italy, in 1891 and 1894, defining the boundaries between British colonial territory and the alleged protectorate. Menilek, however, refused to accept the Italian interpretation of the Wechale agreement. Despite his earlier collaboration with the Italians, he wrote a forceful letter to King Umberto I of Italy (ruled 1878-1900), in September 1890, to observe:

When I made that treaty of friendship with Italy, in order that our secrets and our understanding should not be spoiled, I said that because of our friendship, our affairs in Europe might be carried on with the aid· of the Sovereign of Italy, but I have not made any treaty which obliges me to do so, and today I am not the man to accept it. That one independent power does not seek the aid of another to carry on its affairs your Majesty understands very well.

After many months’ delay, which he turned to good advantage by importing large quantities of fire-arms, mainly from France and Russia, he denounced the treaty of Wechale, in February 1893, and wrote to inform the European powers of this, declaring: “Ethiopia has need of no one; she stretches out her hands to God.”

Fighting between the Italians and Ras Mailgasha [1865-1906], the ruler of Tegre, began in January 1895. The invaders were at first victorious and succeeded in occupying a large stretch of territory, including Adegrat, Maqale, and Amba Alagi. Later in the year, however, Menilek moved north with a large army and forced the enemy to fall back on Adwa (Adowa). The first weeks of 1896 were a period of inaction, neither army desiring to take the initiative. On February 25, however, the Italian prime minister, Francesco Cris pi (1819-1901), exasperated by the delay, despatched a fateful telegram to the Italian commander, General Oreste Baratieri, saying: “This is a military phthisis, not a war … a waste of heroism, without any corresponding success. It is clear to me that there is no fundamental plan in this campaign, and I should like one to be formulated. We are ready for any sacrifice in order to save the honour of the army and the prestige of the monarchy.” Baratieri’s response was to order his army to attack.

The Battle of Adwa

In the ensuing battle of Adwa, which was fought on March 1, 1896, Menilek was in a relatively good position. He had been able to mobilise a large army, including 10,000 men armed with modern rifles, many of which, as an Amharic poem composed after the war was quick to note, had been obtained from Italy during the previous period of cooperation.

The Italians had somewhat more cannon – 56 as against Menilek’s 40 but only about 17,000 men, of whom 10,000 were Italian and the rest Eritrean. Many of the local population were moreover strongly opposed to the Italians, who had expropriated a sizeable amount of land in an attempt to settle Italian colonists, and were therefore willing to show the Ethiopian troops the best paths and to report on enemy movements. The Italians, on the other hand, had no accurate maps and moved in the mountainous terrain in much confusion. The battle resulted in the complete defeat of the invaders, who ceased to be a fighting force after they had lost 43 percent of their men, besides all their cannon and five-sevenths of their rifles. When news of the debacle reached Italy, there were demonstrations in the main Italian cities, and Crispi’s government resigned.

Menilek’s victory, the most remarkable triumph of an African over a European army since the time of the Carthaginian military leader Hannibal (247-182 BC), brought an end, at least ·for the time being, to Italian expansion. In October 1896, the Italians signed the Peace Treaty of Addis Ababa, wherein they agreed to the annulment of the Wechale agreement, and recognized the absolute independence of Ethiopia. Menilek, on the other hand, accepted the continued rule of the Italians in Eritrea, in all probability because he had no wish for further military confrontation with a European power.

The battle of Adwa gave Menilek considerable international prestige. In the ensuing months, the French and British governments dispatched envoys to sign treaties of friendship with him, while other missions arrived from the Sudanese Mahdists, the Ottoman sultan, and the Russian Tsar, while the French, British, Russians, and Italians opened permanent legations in Addis Ababa.

Increasing interest in Ethiopia, the last truly independent state in sub-Saharan. Africa was also evinced by several black intellectuals, among them a Haitian nationalist, Benito Sylvain, and William H. Ellis from the United States, both of whom visited the country in the early years of the century. Interest among the indigenous population of South Africa likewise led to the founding of several Christian churches there which employed the name of Ethiopia.

Southern Expeditions – Menilek, meanwhile, was continuing his expeditions to the south. A first expedition to Borana in 1896 was followed by the occupation of that province, as well as of Konso, in 1897. Hopes of establishing an Equatorial Province, stretching as far south as the 2nd parallel of the north; latitude, which would have included the northern part of what is now Kenya, were dashed, however, in large measure because of the inexperience of the Russian adventurer entrusted with the task.

In 1898 Menilek embarked on a potentially even more important military and diplomatic venture when he sent one of his commanders, Ras Tassamma Nadaw [18? -1911], as far as the White Nile with instructions to make contact with a French force under Captain Jean-Baptiste Marchand which was due to arrive there from the west. Marchand, however, failed to appear when expected, and Tas-samma was obliged to withdraw because of an outbreak of fever among his men. Hopes of close Franco-Ethiopian cooperation were greatly weakened by the ensuing confrontation between the British and the French at Fashoda in the Sudan, for Marchand’s withdrawal in the face of British pressure made it apparent that France had surrendered to Britain, which had, thereby gained a paramount interest in the area.

The Modernisation Program – Menilek throughout this period was increasingly active in modernising his age-old country. In the mid-1880s he had moved his capital to the site of present-day Addis Ababa, which was given its name – literally “New Flower ” – by his consort, Empress Taytu Betul [reigned. 1889-1913], in 1887. By 1910 the town was said to have a population of 70,000 permanent and 30,000 to 50,000 temporary inhabitants. In 1892 the innovating ruler reorganised the tax system by introducing a tithe for the upkeep of the army, thereby terminating the traditional practice whereby the soldiers looted from the peasants. In 1894 he established the country’s first national currency, which circulated beside the old Maria Theresa dollar from Austria.

A proclamation declared that the new money had been introduced “in order that our country may increase in honour and our commerce prosper.” In the same year he also introduced the first postage stamps, and Ethiopia subsequently joined the Universal Postal Union (U.P.U.) in 1908. Also in 1894, Menilek granted a concession for a railway from Addis Ababa to the French Somaliland port of Jibuti, but technical, financial, and political difficulties were so considerable that the line did not reach Dire Dawa in, the semi-desert lowlands to the east until 1902, or Akaki, 14 mi (23 km) from Addis Ababa, until 1915. Telegraph lines to Jibuti, Eritrea, and several provincial capitals were laid by French and Italian engineers ‘in the next few years. Other developments of the period included the dispatch of students abroad, to Switzerland and Russia, the introduction, possibly by the Frenchman· C. MondonVidailhet, of the eucalyptus tree, which did much to alleviate the capital’s previous shortage of wood, and the construction of the country’s first modern bridges.

The early years of the 20th century saw the establishment of a number of other modern institutions. A mint was established in 1902, and at about the same time work began on the first modem road from Addis Ababa to Addis Alam, 38 mi (60 km) west of the capital, as well as another to link the old commercial centre of Harar with the new railway town of Dire Dawa. The Bank of Abyssinia was founded in 1905 as an affiliate of the British-owned National Bank of Egypt. The first modern hotel, the Etege (literally “Empress”) was established in 1907 on the initiative of Empress Taytu, and in the same year the ailing monarch, faced, with the increasing complexity of government, established the country’s first cabinet, which, according to his chronicler, Gabra Selasse Walda Araqay, stemmed from his master’s desire to implant European customs.

The first modern educational establishment, the Menilek II school, was set up in Addis Ababa in 1908 with the help of Coptic ‘1 teachers from Egypt, who also opened schools in Harar, Ankobar, 75 mi (120 km) to the northeast, and Dessie, 155 mi (248 km) to the northeast.

The first government hospital, the Menilek II hospital, was founded in 1910 to replace an earlier Russian Red Cross hospital founded immediately. after the Adwa War and the first government printing press was established in 1911. By the end of the first decade or so of the 20th century, Ethiopia had thus been endowed with. many of the institutions of a modern state.

Menilek’s Diplomacy

Menilek’s greatest achievement was, however, the maintenance of his country’s independence throughout the later period of the Scramble for Africa. While using many foreigners in the modernising process, he was careful not to fall under the influence of any foreign power and displayed considerable diplomatic skill in withstanding the pressures of the three neighbouring colonial powers, Italy, France, and, Britain, which he successfully played off one against the other. His ability in thus making use of the foreign powers and their representatives, and avoiding being used by them, was recognized by the British envoy, Captain John Harrington, who observed of himself and his colleagues in 1902:

I have not yet seen that any of us has what I could really call influence i.e. influence that would make Menilek do what he did not want to do. Influence to the detriment of others is plentiful here, but to one’s own advantage is decidedly infinitesimal.

Menilek’s successful diplomacy was resented by the three colonial powers who, anticipating that the Emperor’s failing health would lead to his rapid demise and the disintegration of his empire, decided in 1906 to cooperate together instead of competing among themselves. On December 13 they signed a Tripartite Convention which stated that, in the event of the status quo being, disturbed, they agreed to work together to safeguard their interests.

These were stated to comprise: (1) a British interest in the Nile Valley, and hence in the area of the Blue Nile; (a) an Italian interest in Eritrea and Somalia, and hence in adjacent areas of Ethiopia; and (3) a French interest in the French Somali Protectorate, and hence its hinterland.

Ethiopia was thus divided into three spheres of influence. Harnngton, one of the principal architects of the agreement, bluntly declared that it had been conceived “in the interests of whites against blacks.”

PHOTO CAPTION: An Ethiopian guard keeps watch from an improvised watchtower. SOURCE: EA Library

Menilek, who was naturally disturbed by this tum of events was not impressed by the foreign powers’ pretensions to have acted to preserve the integrity of his country and commented with irony: The convention of the three Powers has reached me. I thank them for having acquainted me with desires to consolidate the independence of our Realm. But this actual Convention. is subordinate to our authority … [and] cannot in any way bind our decision.

LEJ IYASU

Events in the last years of the reign were seriously affected by Menilek’s failing health, which led to uncertainty over the succession, and the slowing down of the earlier impulse for modemization. In 1909 the old monarch nominated his 11-year-old grandson, Lej Iyasu (q.v.) [1894-1935], son of Ras Mikael, the ruler of Wallo, as his heir, and his cousin, the veteran Ras Tassamma, as regent.

When Ras Tassamma, who would have been a force for stability, died in 1911, the young and inexperienced prince, whose loyalties were probably to Wallo rather than to Shawa, alienated many of the Shawan nobles who had enjoyed a dominant position under Menilek’s rule. During World War I, in the hope of gaining the support of the Muslims, and probably also hoping to obtain access to the sea, then denied him by the Italians, French, and British on the coast, Iyasu entered into friendly relations with the latter’s enemies, the Germans, Austrians, and Turks. A rebellion, encouraged by the Allied powers, broke out in 1916. Iyasu was then deposed by the Sha wan nobility, who decided that Menilek’s daughter Zawditu should become empress and that Tafari, Makonnen, son of the old monarch’s cousin, Ras Makonnen (q.v.), a sometime governor of Harar, should be regent and heir to the throne.

RAS TAFARl’S REGENCY

This settlement of the succession issue provided the country, in Tafari, later to become Emperor Haile Selassie (Hayla Sellasé) [reigned 1930-74), with an energetic leader who resumed the work of modernisation initiated by Menilek. Government was, however, often deadlocked by the division of authority between empress and regent, each of whom had a separate palace and a separate following, and tended to act independently of one another. One of the first reforms of the period was the extension of the system of ministries by the establishment, in 1922, of a Ministry of Commerce, as well as of a Public Works Department which supervised the construction of several new roads. The regent, who was responsible for his country’s foreign policy, obtained Ethiopia’s admission to the League of Nations on September 28, 1923,

In the following year a decree was issued for the gradual eradication of slavery, after which Tafari undertook a European tour which brought him into contact with foreign statesmen and helped to awaken his compatriots to the need to take into account the outside world. When in 1925 the British foreign secretary, Sir Austin Chamberlain (term of office 1924-29), agreed with the Italian Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini (in power 1922-43) that Ethiopia was still partitioned on the basis of the Tripartite agreement of 1906, Tafari protested vigorously. He nevertheless arranged for the signing, in 1928, of a 20-year treaty of friendship and conciliation with Italy.

Other developments of these years included the founding, in 1923, of the regent’s Berhanena Salam printing press, which resulted in the production of a considerable amount of publications in Amharic, and the consequent evolution of Ethiopian literature; the dispatch for study abroad of more Ethiopian students, 25 of whom were in Europe and the United States in 1924; the establishment, also in 1924, of Addis Ababa’s second modem hospital, the Bet Sayda; and the opening in 1925 of a new modern school, called after Tafari Makonnen.

PHOTO CAPTION: Ahuna Matewos (left), the Empress Zawditu, and Walda Giyorgis (right). SOURCE: EA Library

In 1926 the regent engaged a Belgian mission to train his bodyguard. The advent of airplanes to Ethiopia had for some time been prevented by the conservatism of some of the nobles, but in 1929 Tafari arranged for the first five planes -from France, Germany, and Italy, – to be brought in.

HAILE SELASSIE

Modernisation Continues – When Empress Zawditu died in 1930, she was succeeded, in accordance with the earlier compact, by Tafari Makonnen, who assumed the throne as Emperor Haile Selassie. News of his coronation, in November, was not without its impact outside the country. in particular, it gave birth to the Ras Tafari movement in Jamaica, where the idea gained ground that a postcard bearing the emperor’s photograph would serve as a passport enabling its holder to return to Africa.

In Ethiopia, meanwhile, the process of modernisation continued for the next half-decade, and with it a tendency toward greater centralization of power. The establishment in 1930 of a Ministry of Education, and the passage of a law providing for the survey and registration of land, was followed in 1931 by the nationalization of the old Bank of Abyssinia, its replacement by a government institution, the Bank of Ethiopia, and the issuance of a new currency. In the same year the country’s first written constitution, with a twochamber nominated parliament, was introduced, but with the emperor retaining all real power. At the same time, a new anti-slavery decree was promulgated which accelerated the pace of emancipation, particularly after the establishment of an anti-slavery office the following year. A Ministry of Public Works was also set up in 1932, and a temporary radio station in 1933, which was replaced by a more powerful installation in 1935. The road network, which was based on Addis Ababa, was meanwhile extended north to Dessie, northwestwards to Dabra Libanos, with a rough track leading on to Dabra Marqos in Gojam, westwards to the Gibe river, and southwestwards to Jimma. Communications to the east were still mainly based on the railway, though a track had been constructed eastwards from Dire Dawa to the British Somaliland frontier, and work began in the west on a road to lead from Gore to Gambela, ail inland port on the Baro River, a tributary of the White Nile.

Several new schools were also opened in, these years, among them in 1931 the first school for girls, called after the emperor’s consort, the Empress Manan [reigned 1930-62]. By the eve of the Italian invasion of 1935, there were 14 government schools in the capital, but with an enrollment of only about 4,200 students, four-fifths of them boys. Educational establishments had also by then been opened in the provinces. The number of students sent abroad by the government likewise significantly increased, and students who had completed their studies began to enter government service. A score or so of hospitals were opened in this period, mainly by missionary organisations, which also provided some elementary schooling. Other developments, towards the end of the period, included the founding of a military college at Holeta, 28 mi (45 km) west of the capital, with the aid of Swedish officers, in 1934, the issue in the same year of a decree to check, the exaction of forced labour from the peasantry, and a law, enacted in 1935, for the improvement and monetarization of the land tax. Such reforms, which represented the further consolidation of the modernizing trend, were, however, by then overshadowed by the threat of attack from Fascist Italy – an attack which; when it came, was to constitute another turning point in Ethiopian history.

The Italo-Ethiopian Crisis

The conflict between Ethiopia and Italy was in large measure the personal responsibility of the Fascist dictator Mussolini, who, in the early 1930s, turned his attention to the far-off African state the cause, as he saw it, of his nation’s humiliation at the battle of Adwa a third of a century earlier. Ethiopia was also, in his view, the only country on the continent still available for colonisation. Early in 1932, he dispatched his minister of Colonies, General Emilio De Bono (1866-1944), to Eritrea on a visit of inspection. On the minister’s return, the Fascist leadership decided that Italy’s “colonial future must be sought in Africa.” The Duce (literally “leader,” the title then accorded to the dictator), thereupon ordered De Bono “to go full speed ahead,” and to be ready for war “as soon as possible.”

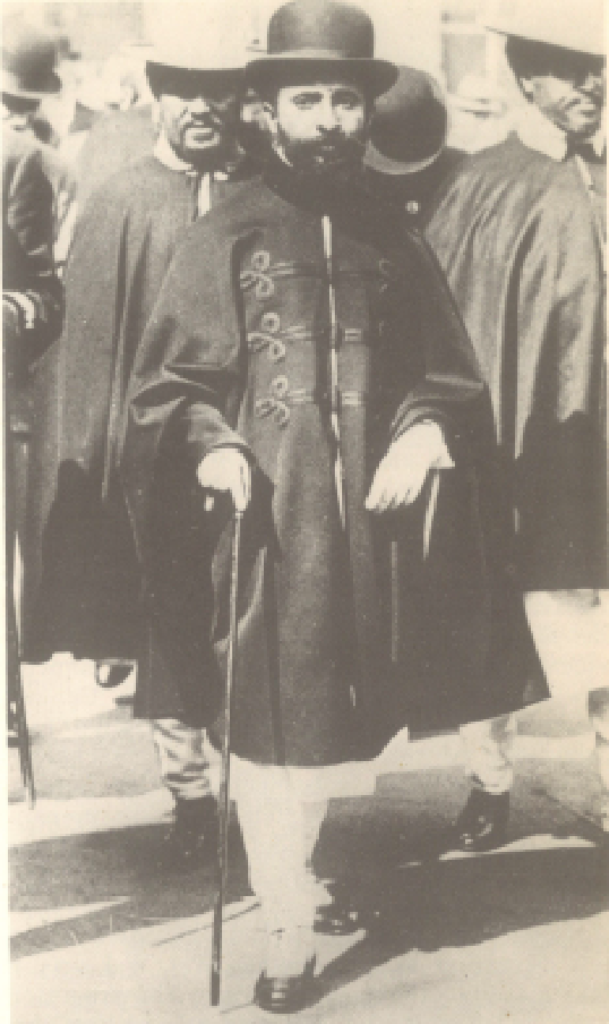

PHOTO CAPTION: Tafuri, later to become Emperor Haile Selassie I, visiting London. SOURCE: EA Library

The pretext for the invasion of Ethiopia came at the end of 1934 when a joint Anglo-Ethiopian boundary commission, which had been surveying the frontier of British Somaliland, found a force of Italian troops at Wal Wal, a post 62 mi (100 km) on the Ethiopian side of the Italian Somaliland border. The British members of the commission protested at the Italian presence and withdrew to avoid an international incident, but the Ethiopians stood their ground. The two forces faced each other for about two weeks, until December 5, when a shot of indeterminate origin provoked a clash of arms.

The Italian government at once seized upon the incident to demand that–Ethiopia should apologize, salute the Italian flag at Wal Wal – thereby recognising Italian sovereignty over the area – and pay compensation. The Ethiopian government, reluctant to accept the loss of territory involved, refused these demands and proposed instead that the dispute be referred to arbitration in accordance with the Halo-Ethiopian friendship treaty of 1928.

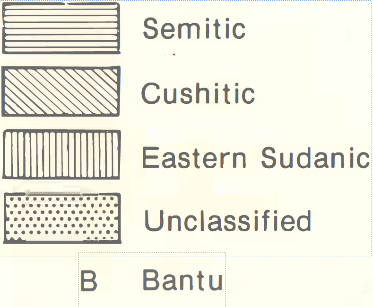

PHOTO CAPTION: The proclamation of the Ethiopian constitution of 1931. SOURCE: EA Library

Mussolini rejected this suggestion, whereupon the emperor appealed to the League of Nations in Geneva, Switzerland. The international organisation took cognisance of this request, but its machinery, which was deliberately hampered by the Italians, who needed time to complete their war preparations, moved so slowly that the verdict of the League’s arbitrator was not given until September 3, 1935. Even then it was entirely inconclusive, for Mussolini’s representatives had refused to accept any discussion as to whether Wal Wal was in Ethiopia or in the Italian colony. The arbitrators could only report that the incident was “an accident for which no blame could be attributed to either side; the Italian and Ethiopian authorities both believed Wal Wal to be in their own territory.” While the League was arriving at this scarcely very meaningful decision, the Fascist leaders had been pushing forward with the military preparations, turning the Italian colonies of Eritrea and ” Somaliland into bases for the impending invasion. About 170,000 soldiers, an immense quantity of military supplies, had been shipped out from Italy, while 65,000 Eritrean troops had been mobilised.

Despite mounting evidence of Italy’s aggressive designs, the British and French, who controlled Ethiopia’s only access to the sea other than through Italian territory, imposed an arms blockade, on July 25, 1935, on both parties to the dispute. This seriously curtailed Ethiopian arms imports while leaving Italy’s power to manufacture its own weapons unaffected. The emperor, drawing attention to the injustice of this policy, observed:

Is there one policy for the weak and another for the strong? The weak must be kept weak so that the strong may have no difficulty in destroying them. Italy is a great manufacturing country working day and night to equip her soldiers with modern weapons. We are a pastoral and agricultural people, without resources and cannot do more than purchase abroad a few rifles and guns … If we are in the right, and if civilised nations are unable to prevent this war, at least do not let them deny us the power of defending ourselves.

The Halo-Ethiopian crisis aroused immense international interest, the more so as it seems to many a test case as to whether the League of Nations would be able to realize the aim of its covenant in establishing collective security and thus in effect banishing war. Mussolini, it should be emphasised, had left no doubt as to his intention of conquering Ethiopia, and in one of his bombastic speeches declared, for example, on August 18, 1935: “We must go forward until we achieve the Fascist Empire.” Concern with the threatened conflict was widely felt, not least by the British and French governments.

On September 10, Pierre Laval, French prime minister and minister of foreign affairs, and Sir Samuel Hoare, British foreign secretary, held a secret meeting at which, as Laval later revealed, they found themselves “instantaneously in agreement upon ruling out military sanctions, not adopting any measure of a naval blockade, and never contemplating the closing of the Suez Canal – in a word, ruling out everything that might lead to war.” Publicly, however, the British and French leaders spoke in a very different vein. On the following day Sir Samuel, in an address to the League of Nations, declared:

His Majesty’s Government and the British people maintain their support of the League, and its,.ideals, as the most effective way of ensuring peace … The League stands, and my country stands with it, for the collective maintenance of the Covenant in its entirety, and particularly for steady and collective resistance to all acts of unprovoked aggression.

The Italian antifascist historian, Professor Gaetano Salvemini, commenting on, this famous speech, sagely declared that if the previous Anglo-French agreement had been known, the British leader’s address “would have been greeted with a tempest of boos and hisses,” but, not being known, “met with an immense ovation.”

The Italian Invasion

By the end of the rainy season of 1935, Fascist Italy had completed its military preparations. The long-expected attack began, without any declaration of war, on October 3, when Adwa was bombed, and an Italian army of 100,000 exceedingly well-armed men crossed the frontier from Eritrea. A second but less impressive Italian force attacked Ethiopia from the Italian colony of Somalia in the south. Faced with the opening of hostilities, the League of Nations decided, on October 9, by 50 votes to 1 (Italy), with 3 abstentions (Albania, Austria, and Hungary), that Italy was guilty of aggression.

PHOTO CAPTION: Ethiopian forces gather on the plain of Addis Ababa in 1935. SOURCE: EA Library

Sanctions against Italy, in the form of a prohibition on member states from trading in certain articles with that country, was decided upon. The prohibition did not, however, extend to petroleum, without which the invading armies would have been immobilised. Nor was the Suez Canal closed – a step that would have brought the war to a speedy close. The League’s sanctions, as the British statesman Winston Churchill (1874-1965) was later to observe, were thus, ”not real sanctions to paralyze the aggressor, but merely such sanctions as the aggressor would tolerate.” The case for imposing oil sanctions was still under discussion when the French press, on December 9, 1935, leaked details of the so-called Hoare-Laval Plan.

This agreement, which Sir Samuel Hoare and Pierre Laval had concluded in t secret, would have obliged Ethiopia to surrender the Ogaden and a large portion of Tegie in return for a port, while virtually all the country south of Addis Ababa was to be allocated to Italy as a “zone of economic expansion.” These amazing proposals, which would have given the aggressor control of most of Ethiopia and which neither that country nor Italy ever accepted, created such an outcry that Sir Samuel was obliged to resign, but the fact that they could have been put forward at all effectively destroyed all hopes of introducing oil sanctions.

Mussolini later observed to Adolf Hitler (dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945), that if the League had indeed adopted the oil sanctions, he would have been obliged “to withdraw from Abyssinia within a week.” The Italians, meanwhile, had been continuing their military offensive, but at first only with great difficulty. De Bono’s army took more than a month to reach Maqalé, little over 62 mi (100 km) from the frontier, after which the Italian commander, fearing to over-extend his lines of communication: called a halt to reorganise his forces. Mussolini, infuriated by this sign of Fascist weakness, which might be expected to give heart to protagonists of more effective sanctions, ordered that the advance should continue “without hesitation.” The general replied that considerations of military necessity should be given priority, and was accordingly dismissed, on November 14, in favour of General Pietro Badoglio, who agreed to an accelerated prosecution of the war. The Ethiopians, however, staged a successful counter-attack in the middle of December, whereupon the Duce, insistent on a speedy victory, authorised Badoglio, on December 28, to use poison gas, “even on a large scale.” The Italian air force then began spraying mustard gas from the air – an action which, according to the British military analyst Major-General J. F. C. Fuller (1878-1966), was “the decisive tactical factor” in the war.

By the first months of 1936, Italy’s overwhelming military superiority, both on the ground and in the air, had proved decisive, and the Ethiopian armies, which were virtually without any defence against Italian attack from the air, began to crumble. In February, Ras Mulugeta Yegazu, the Ethiopian Minister of War, was defeated at Amba (Mount) Aradam in Tegre, and two of the principal Ethiopian leaders, Ras Kassa Haylu and Ras Seyum Mangasha, were obliged to retreat. A third commander, Ras Emiru, was defeated in Shire, on March 1, and the emperor’s forces were overwhelmed near Lake Ashangi at the end of the month. Haile Selassie fled southwards to Addis Ababa, but preferring to appeal to the outside world rather than to continue resistance in person, left his capital for Europe on May 2. His departure was the signal for extensive arson and looting, in part inspired by the desire to deny as much as possible of the capital to the invader. Italian forces occupied the city without opposition three days later, and on May 9 Mussolini proclaimed the annexation of Ethiopia and the creation of his Fascist empire.

The Emperor’s Appeal to the League

The League of Nations soon abandoned the question of Ethiopia. At a dinner attended by influential persons in London on June 10, one of the speakers, the Conservative Businessman Sir Robert Horne (1871-1940), announced his desire to see the end of sanctions, and observed: “When there is a corpse in your midst, it, is better to bury it.”

The British 1 chancellor of the exchequer, Sir Neville Chamberlain (term of office 1931-37), later to become prime minister from 1937 to 1940, agreed, declaring that sanctions had been “the very midsummer of madness.” At the end of the month, the emperor travelled to Geneva, and, informed the League Assembly that he had come to claim “that justice that is due to my people.” Declaring that “God and history will remember your judgement,” he asked: “What answer am I to take back to my people?” The reply came on July 4, when the League voted by 44 votes to 1 (Ethiopia), with 4 abstentions (Chile, Mexico, Panama, and South Africa), to terminate sanctions. They were formally lifted on July 15. That day Mussolini triumphantly commented: “The white flag has been hoisted on the ramparts of the Sanctionist States … So it has happened, and so· it will happen … always.”

PHOTO CAPTION: Ethiopia mobilises its forces against the impending Italian attack. SOURCE: EA Library

Despite the failure of sanctions, the war proved well-nigh disastrous for Italy. The country’s stock of gold and foreign currency was so severely depleted that a much-publicized campaign was launched to induce Italian women to part with their wedding rings. Such gestures had, however, but little effect and Mussolini was obliged, on October 5, 1936, to devalue the Italian lira by no less than 59 percent. Economic difficulties produced by the war and intensified by sanctions, had the effect, furthermore, of pushing Italy on to the path of autarchy (economic self-sufficiency), as well as of shifting Italian trade from sanctions to non-sanctionist countries, above all Germany, and were thus instrumental in bringing Mussolini closer to Hitler, paving the way for the Rome-Berlin Axis, or “Pact of Steel,” as the Duce called it.

International Reactions

Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia, one of the major events of the “Appeasement ” period prior to World War II, also regarded by some, as the “First of the League Wars,” made a deep impression on international opinion, not least in Britain.

Even before the outbreak of hostilities, a voluntary society, the League of Nations Union, had held a “peace ballot,” in which eleven and a half million people voted, more than half as many as in a general election, and 90 percent favoured the imposition of sanctions on the aggressor. Later, an Abyssinian Association was established in support of the Ethiopian cause, while a weekly newspaper, New Times and Ethiopian News, edited by the former suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst [1882-1960], published news of Ethiopian resistance to the invader, and demanded that the case of Ethiopia should not be forgotten. The war also made a strong impact on Africans and people of African descent, many of whom saw it as the greatest colonial war ever fought on the African continent.

Even before the outbreak of hostilities, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Mrs. Marcus Garvey, wife of the charismatic Jamaican who had established the “Back-to-Africa ” movement in the United States, George Padmore from the West Indies, and other Pan-Africanists in London, had founded the International African Friends of Abyssinia, to rally support for Ethiopia. Kwame Nkrumah (1909-72), later to become the first president of Ghana, and then a student passing through England on his way to the United States, recalled that when he saw posters announcing “Italy Invades Abyssinia,” his “nationalism surged to the fore.” The Nigerian nationalist leader Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe later wrote with enthusiasm, in his book Renascent Africa (1937), students in the Gold Coast who had collected their pennies for the Ethiopian cause, and commented that wherever these youngsters went in years to come they would idolize the heroes of Ethiopia’s resistance, and point to what had been done “to postpone the crystallization and realisation of an area of man’s humanity to man, on this paradise of stately palms – Africa.”

In Sierra Leone, Wallace Johnson, founder of the West African Youth League, wrote to the African Morning Post in angrier terms to declare that the European God was “spelt Deceit,” for His law was: “Ye strong, you must weaken the weak. Ye ‘civilized’ Europeans, you must ‘civilize’ the ‘barbarous’ Africans with machine guns. Ye Christian Europeans you must ‘Christianise’ the pagan Africans with bombs, poison gasses.” Such attitudes were typical of much African thinking in this period and played their part in the subsequent upsurge of African consciousness during the next few decades.

The Italian Occupation. The Fascist occupation of Ethiopia, which for the first time brought the bulk of the Horn of Africa under a single administration, was accompanied by massive Italian expenditure: The need to conquer and occupy the country, as well as hopes of subsequently exploiting it, caused the invaders to, devote much of their attention to road-building. For a time, no less than 60,000 Italians were occupied on this work, though by 1939 this figure had fallen to 12,000 Italians assisted by 52,000 Ethiopians, Eritreans, and other ‘natives.’ An empire-wide road network, stretching from the port of Massawa, in Eritrea, on the Red Sea, to Mogadiscio (Mogadishu) in Italian Somaliland, on the Indian Ocean, was thus established but only at the price of restricting most other developmental activity. Industrialization was limited, largely due to shortage of funds, and in part perhaps because it would have competed with Italian industry. Trade suffered from Italian Fascist xenophobia (hatred of foreigners), which resulted in the expulsion of Indian and other foreign merchants, as well as from efforts to replace the old silver Maria Theresa dollar with largely unacceptable Italian paper money, as well as by the establishment of large and excessively bureaucratic commercial corporations. Fascist belief that Italy was overpopulated led to grandiose settlement schemes which largely failed to materialize. Badoglio was quoted, in 1936, as declaring that it was “not an exaggeration” to envisage the coming of Ethiopia of 1,000,000 Italian settlers. As a result of a lack of capital, however, as well as because, of resistance by the Ethiopian patriots, less than 4,000 families had been established on the land by 1940.

To cater for the growing Italian population, consisting mainly of soldiers and administrators, and which by 1939 exceeded 130,000 in the whole of Italian East Africa, a significant number of European-type buildings were nevertheless erected, mainly in Addis Ababa, where supplies of electricity and piped water were greatly improved, and in the three provincial capitals of Goodar, Jimma, and Harar. House-building was carried out on the basis of rigid racial segregation, with the establishment of “European” and “native” quarters -and the eviction of about 20,000 Ethiopians from the part of Addis Ababa reserved for Italian habitation. Intermarriage or even cohabitation between Italians and “natives” was prohibited by legislation enacted for the “defence” of the Italian race. Several new hospitals were erected, mainly for Europeans, though the “native population” benefited from preventive medicine measures, which seem to have reduced epidemics. The education of the “natives” was, on the other hand, strictly curtailed. Several of the former Ethiopian schools were taken over for Italian children, while textbooks were designed mainly to inculcate ideas of loyalty to Italy and its Duce. Several national monuments were removed, from Ethiopia, including one of the ancient obelisks of Aksum, which was taken to Rome, where it still stands (despite a demand by the post-war Ethiopian parliament for its return).

The Patriot Resistance

The Italians, though in control of the towns, were faced with armed resistance in much of the countryside, particularly in the mountainous regions of Shawa Amhara and Gojam, where numerous Patriot leaders emerged, some of the most prominent of whom were Ababa Aragay, Abara Kassa, Balay Zalaqa, and Geresu Duke. Patriot forces attacked Addis Ababa, unsuccessfully, in August 1936 and later launched assaults on Italian forces and communications in other areas.

PHOTO CAPTION: Haile Selassie I: A wartime photograph. SOURCE: EA Library

Opposition was intensified after an attempt on the life of the Italian viceroy, General Rodolfo Graziani, in February 1937 by two Eritreans, Abraha Deboch and Mogus Asgadom, which was followed by a three-day massacre in which the local Fascists deliberately slaughtered several thousands of innocent inhabitants of, Addis Ababa, among them many of the modem educated class. Faced with constant rebellions, Graziani, often acting on personal orders from the Duce, carried out a policy of remarkable ruthlessness and brutality. There were, as is evident from the viceroy’s telegram to Rome, numerous summary executions, including the killing of more than 100 monks at the monastery of Dabra Libanos, and mass deportations to concentration camps, as well as the dropping of poison gas on areas of “disaffection.” Graziani, who proved unable to crush the Patriot movement, was dismissed, together with the Italian minister of the colonies, Allessandro Lessona, at the end of 1937, and was replaced as viceroy by the Duke of Aosta(term of office 1937-41), who, though responsible for increasing racial discrimination in the empire, attempted in other respects to follow a somewhat more liberal policy in the hope of winning local support for his rule. Mussolini’s son-in-law, and minister of foreign affairs, Count Galeazzo Ciano (term of office 1936-43), noted in his diary, on January 1, 1939, that Amhara was “still in a state of complete revolt.” Not long afterwards the viceroy confided to him that the attempt at “pacifying” the empire would be entirely jeopardised in the event of Mussolini becoming embroiled in a conflict with France.

On the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, the Duce avoided immediate involvement, in part at least because of the uncertain position of his armies in Africa, When the fall of France became imminent, however, he declared war on that country, as well as on Britain, on June 10, 1940. His entry into the European war brought about a radical change in the situation in East Africa, for the Italian armies there were cut off from Italy overnight, while the Ethiopian Patriots, after four years of lone struggle, at last, found themselves with allies. The Fascist armies easily occupied British Somaliland, and crossed the frontier into the Sudan and Kenya, but, severely inconvenienced by increasing Patriot opposition within Ethiopia, were soon also attacked by powerful Allied armies.

Emperor Haile Selassie, who had been living in exile in England, was meanwhile attempting to obtain British recognition as an ally. At the beginning of the European war in 1939 he had offered his services to the British government, which, fearing to offend Mussolini who was still officially neutral – or, as he termed it, “pre-belligerent” had failed to respond to the royal Ethiopian exile. Even after ·Italy’s entry into the European conflict the British government continued to treat the latter with caution. The British were reluctant to consider an African state as an equal, or to support what was widely considered as a “native insurrection” against a legally constituted colonial regime, for Britain had recognized Italy’s conquest on April 16, 1938. There was, moreover, skepticism as to whether the emperor would be able to rally the Ethiopian population to his support, and, if rallied, whether it would contribute materially to the Allied war effort. Haile Selassie’s personality, and memories of the failure of Britain and the League of Nations to assist Ethiopia half a decade earlier, had, however, made a deep impact on public opinion in Britain. The British government accordingly agreed, with some reluctance, that Ethiopia and the emperor be granted the status of an ally. On July 25, 1940, he flew to the Sudan where he was again confronted by British procrastination, though most of the Ethiopian refugees in that territory offered to join him.

British war strategy now necessitated the defeat of the Italians, whose position in East Africa threatened Allied communications with India and the East. The British military authorities therefore decided to attempt to make use of the Ethiopian Patriots Mission, a small force of five Britons and five Ethiopians, led by a British officer, Colonel Daniel Sandford (1882-1972), was accordingly sent into Gojam in August. Subsequently, on learning of the extent of opposition to the Italians, a British ministerial conference was held, in October, in Khartoum, capital of the then Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, where it was agreed that Ethiopians fighting against the common enemy would be accorded the title of Patriots, rather than rebels against Italian rule, and that Haile Selassie would be provided with a small quantity of arms. In November 1940, another British officer, Colonel Orde Wingate, was flown into Go Jam with promises of speedy if limited aid.

The Liberation

The main campaign against the Italians in East Africa began on January 19, 1941, when an Allied army, led by Lieutenant-General William Platt, entered Eritrea from the Sudan, but made only slow progress, being held up by particularly strong Italian resistance at Keren in Eritrea.

On January 20, the emperor, with Wingate as his main adviser, had meanwhile crossed the frontier into Ethiopia, further to the south at Om Idla. Receiving strong support from the Patriots in Gojam, he advanced without much difficulty across the greater part of that province. A third Allied force, largely composed of South Africans, and led by Lieutenant-General Sir Alan Cunningham, had at about the same time crossed the frontier from Kenya, on January 24. Easily defeating the Italian forces, it swept through Harar to Addis Ababa, which it entered on April 6. News of the Allied advance soon demoralized the Italian army, resulting in extensive desertion among the Italians’ “native” troops, as well as a resurgence of Patriot activity.

The question of Anglo-Ethiopian relations began to loom large in the latter part of the campaign. The emperor wished to enter Addis Ababa, immediately after its occupation by the South Africans; but this was vetoed by the British on the grounds that the immediate resumption of Ethiopian rule might endanger the lives of the capital’s extensive Italian population. After several weeks of delay, he nevertheless, at Wingate’s suggestion, flouted official British policy by making his way to Addis Ababa, which he entered in triumph on May 5, 1941, the fifth anniversary of the Fascist occupation of the city. On returning to the capital, which had expanded considerably since his departure, he promised to inaugurate a “new era” in Ethiopian history.

The fall of the Fascist regime left the restored Ethiopian government with a number of major problems. The extensive Italian investment in roads and other installations necessitated heavy day-today expenditure although government revenues had been substantially reduced by the fighting and subsequent disruption of economic life. The pre-war Ethiopian government had, moreover, long since been disbanded, and many of the educated Ethiopians, who could have helped to run the administration, had been killed. Large numbers of people, many of them of doubtful loyalty, were in possession of firearms and constituted a potential threat to public order. The Patriots also constituted a problem in that their leaders, some of, whom were not necessarily much qualified for administration, wanted appointment as a reward for past services. The existence of 40,000 Italian civilians, still enemy nationals, who had to be supplied with food and medical services, represented an additional embarrassment.

PHOTO CAPTION: Ethiopian royal cavalry. SOURCE: EA Library

Relations with the British

The first years after the liberation were overshadowed by the question of relations with the British, whose army of liberation soon came to be seen as another occupying force. Tensions between the Ethiopians and British were almost inevitable in view of the fact that joint operations against the Italians had been undertaken hastily, with little deliberation for the future. No formal agreement between the emperor and the British had been concluded, and the only British statement of intent was one made by the foreign secretary, Anthony Eden (term of office 1940-45), on February 4, 1941, that Britain “would welcome the reappearance of an independent Ethiopian state and recognise the claim of Emperor Haile Selassie to the throne.” British officials, meeting in Cairo later in the month and again in March, agreed on “rejection of any idea of a protectorate or the provision of a strong western administration of the country.” After the emperor’s return to Addis Ababa, there was, however, much disagreement between the Ethiopians, and the British. The former expected to assume full sovereignty, while the latter regarded themselves as caretakers in the occupation of enemy territory.