KENYATTA, JOMO

- 6 Min Read

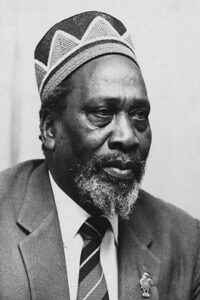

PHOTO CAPTION: Jomo Kenyatta. SOURCE: Mabumbe.com.

Jomo Kenyatta (c. 1895 – August 22, 1978) led Kenya to independence in 1963 and became the country’s first Prime Minister from 1963 to 1964 and its first President from 1964 until he died in 1978. He is widely regarded as the founding father of the Republic of Kenya. An anti-colonial activist and nationalist politician, Kenyatta played a central role in guiding Kenya from British colonial rule to self-government. As president, he promoted racial cooperation, pursued capitalist-oriented economic policies, and adopted a generally pro-Western foreign policy, which helped maintain political stability and attract foreign investment in the early years of independence.

Kenyatta was born as Kamau wa Ngengi (“Kamau, son of Ngengi”) around 1895 in the Gatundu/Ichaweri area of British East Africa (present-day Kenya), within the Kikuyu community. Due to the absence of formal colonial birth records at the time, his exact date and place of birth remain uncertain. He belonged to the Kikuyu ethnic group, for whom land ownership and communal identity were central aspects of social life. Details about his immediate family background vary across sources, but it is generally accepted that he grew up in a rural Kikuyu setting before coming under the influence of missionary education.

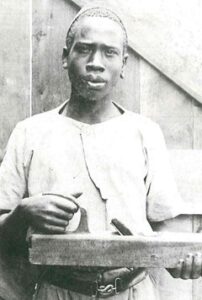

PHOTO CAPTION: Jomo Kenyatta at the Thogoto School. SOURCE: Presidential Library and Archives, Kenya.

In the early 1900s, Kenyatta joined the Thogoto mission school, run by the Church of Scotland, where he received basic formal education while also working to support himself. During this period, he converted to Christianity and was baptised Johnstone Kamau. He later adopted the name Jomo Kenyatta, reflecting cultural symbolism, personal identity, and his growing political consciousness over time.

After the formal establishment of Kenya as a British colony in 1920, Kenyatta moved beyond village life and sought employment in Nairobi. In the early 1920s, he worked in various capacities, including as a store clerk and water reader for the Nairobi Municipal Council. During this period, African political consciousness was beginning to take organised form, particularly among the Kikuyu, who were increasingly affected by land alienation and discriminatory colonial policies.

In 1925, Kenyatta became involved with the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA), initially serving as a translator due to his proficiency in English. He later emerged as one of its leading representatives and was sent to London to petition the British Colonial Office on issues of land rights and African political representation. Although these efforts yielded limited immediate success, they marked the beginning of his long engagement with international advocacy.

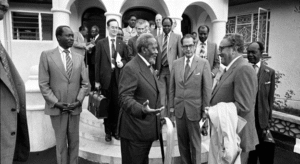

PHOTO CAPTION: Jomo Kenyatta in a diplomatic engagement. SOURCE: The Kenya Times.

Throughout the late 1920s and 1930s, Kenyatta remained in Europe, pursuing further education and interacting with African, Caribbean, and European intellectuals and activists. During this period, he studied at several institutions and, in 1938, published Facing Mount Kenya, a major work that examined Kikuyu society and criticised the social and economic disruptions caused by colonial rule.

Kenyatta’s years abroad were formative, exposing him to Pan-Africanist ideas and international debates on colonialism and self-determination. Influenced by figures such as George Padmore, he refined his political thought and nationalist vision. These experiences further consolidated his public identity as Jomo Kenyatta, a name that came to symbolise his cultural and political stance.

In 1946, Kenyatta returned to Kenya and, in 1947, became president of the Kenya African Union (KAU). Under his leadership, the party advocated African majority rule and sought to unite different ethnic groups against colonial domination. However, white settler resistance and entrenched colonial structures limited the scope of political reform.

In 1952, the declaration of a State of Emergency following the outbreak of the Mau Mau uprising dramatically altered Kenya’s political landscape. The Mau Mau movement represented a militant response to land dispossession and colonial repression, particularly among sections of the Kikuyu population. Although the colonial authorities suspected Kenyatta of involvement, there is no conclusive historical evidence that he led or directed the Mau Mau movement, and he publicly distanced himself from violent methods. Nevertheless, he was arrested on October 20, 1952, tried in a highly controversial and widely criticised trial, and sentenced in April 1953 to imprisonment followed by restriction.

Kenyatta spent several years in prison and was later detained in internal exile in Lodwar, in north-western Kenya. During this period, political developments increasingly favoured African self-rule.

In 1960, the Kenya African National Union (KANU) was formed, and Kenyatta was elected its president while still in detention. KANU refused to participate in the government without his release. In August 1961, Kenyatta was freed, after which he reassured both Africans and settlers of his commitment to reconciliation and stability in an independent Kenya.

PHOTO CAPTION: Jomo Kenyatta, sworn in as President. SOURCE: Presidential Library and Archives, Kenya.

Kenyatta played a leading role in constitutional negotiations in London in 1962, and in May 1963 he led KANU to victory in the pre-independence elections. On December 12, 1963, Kenya attained independence, with Kenyatta becoming Prime Minister. In 1964, Kenya was declared a republic, and Kenyatta was elected its first President.

The legacy of colonialism and the violence of the Emergency period left deep social and political scars, particularly within the Kikuyu community. As president, Kenyatta prioritised national unity and economic growth. Although Kenya gradually evolved into a de facto one-party state under KANU, the country experienced relative political stability.

PHOTO CAPTION: Mzee Jomo Kenyatta listens as the Kenya Rifles band plays a revised Band Version of the Kenya National Anthem on 1st June 1964. SOURCE: Presidential Library and Archives, Kenya.

His government introduced national symbols and policies aimed at fostering a shared Kenyan identity, including the adoption of a national anthem and the promotion of Kiswahili as a unifying language. While colonial symbols were replaced by national ones, this process occurred selectively and gradually rather than through a single, systematic programme of cultural removal.

Kenyatta’s administration also pursued land resettlement and agricultural development programmes intended to address historical land inequalities created under colonial rule, although the outcomes of these policies remained uneven and, at times, controversial.

PHOTO CAPTION: Military officers carrying the casket of Jomo Kenyatta for burial. SOURCE: The Daily Media.

Affectionately known as Mzee (“the old man”) in his later years, Jomo Kenyatta died in his sleep on August 22, 1978, in Mombasa after a period of declining health. He was accorded a full state funeral and buried on August 31, 1978, at a mausoleum within the grounds of Parliament in Nairobi. He was succeeded by Daniel arap Moi, who continued many of his policies and political approaches.

EA EDITORS