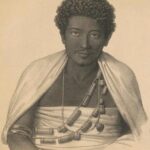

LETSIE I

- 5 Min Read

Letsie I (1811-1893), whose name at birth was Mohato, was the son of Moshoeshoe, king of the Basotho nation, by his principal wife, Mabela. He became the paramount chief of the Basotho of Basutoland (now known as Lesotho), upon the death of his father. He reigned over the Basotho for 21 years, from 1870-91, during which time significant administrative changes were to take place in Basutoland.

Soon after French Protestant missionaries arrived in the country in 1833, Letsie and his brother Morapo were sent by their father to be educated by them. Whatever education they received, the missionaries’ control over Letsie was non-existent. Aggressive in character, at least in his early years, he delighted in launching cattle raids, despite his father’s opposition. In 1835 and 1836, however, with his father’s sanction, he launched notable raids against Nguni and Korana groups.

In 1845 he was sent to Cape Town to receive further education, and was said to have made excellent progress there, although his stay does not appear to have been lengthy. Letsie later played a role in various conflicts and disorders which occurred in the region during Moshoeshoe’s reign. In 1848 and 1853 he led forces against his father’s rival, Sekonyela.

He also played an active role in the conflicts between the Basotho and the Orange Free State known as the First Basuto War of 1858. He took little part in the Second Basuto War of 1865-66 (also known as the Sequiti War) and the Third Basuto War of 1867- 68. But, together with his father, he was active in the peace negotiations at the conclusion of each of these wars.

In the third of these wars, the defeat of the Basotho by the Free State in 1867, and the placing of their territory under British protection in 1868, laid the foundation for further erosion of Basotho indigenous authority. Having officially become a British protectorate named “Basutoland” in 1869, the title of the king of the Basotho was downgraded to paramount chief. In 1871 the formal act of annexation was enacted by the Cape Colony legislature without consultation with the Basotho. The authority to make laws and regulations became the exclusive functions of the Cape governor, who also determined the class of Basotho legal cases that could be adjudicated by the Cape courts. The governor’s agent was empowered with wide administrative discretion and acted as chief magistrate.

In 1877 and 1888 regulations were promulgated that further enhanced the Cape government’s authority over Basutoland by gradually replacing the judicial authority of the chiefs with that of colonial magistrates. The effect of the 1871 and 1877 administrative regulations was to turn Basutoland into a Native Reserve. Although agricultural activity was expanding significantly during this period, it was to be undermined by the greater economic lure of the diamond mines in Kimberley. This was to be the beginning of the migrant labor system in Basutoland.

There was resistance to the new colonial system of authority, however, by many of the Basotho chiefs under the leadership of Paramount Chief Letsie I. As a tactic, for they never seriously considered becoming an integral part of the Cape, the chiefs asked for representation in the Cape Colony parliament. The request was turned down with what seemed to be a vengeance: Basotho taxes were forthwith to be doubled. By obtaining representation in the Cape parliament, Letsie I and the cooperating Basotho chiefs hoped to influence legislation that affected Basutoland.

Letsie I, with his brother Molapo, and Masopha, and his son Lerotholi, opposed the British policy of disarming the Basotho. The chiefs went to war with the British on this issue in the so called Gun War of 1880-81. Although Letsie proclaimed his loyalty to the Cape administration at this time, the Cape doubted his sincerity. The chiefs, moreover, refused to follow his orders. He then submitted to the Cape government and tried to send his guns to Maseru, the Basotho capital.

His son Lerotholi, however, captured his guns on the road. The Cape administration was then defeated by the Basotho chiefs. After this humiliating reverse, the Cape administration was relieved of its responsibility for administering Basutoland by the British imperial government on the condition that the Cape guarantee an annual subsidy of £20,000 to be contributed into Basutoland’s administrative budget.

The Basotho were told by the British that if they wanted they could return to their independent status prior to British protection, a ploy intended to force the rebellious chiefs to accept British imperial terms or face Boer aggression from the Orange Free State. The Basotho Land Disannexation Act was passed by the Cape Colony Parliament in September 1883 and later in November a pitso (or national general assembly) was convened at which the Sotho chiefs under Letsie I and his son Lerotholi agreed to be British subjects despite the opposition of other chiefs. As a result, the British government issued a proclamation on March 18, 1884 announcing the annexation of Basutoland.

It was during Letsie I’s paramountcy that the consultative pitso system began to decline. It met irregularly between 1879-86, and after 1888 it turned into a ceremonial occasion whose main features were the announcements of important developments and the reception of distinguished colonial visitors.

From 1884-94 Resident Commissioner Marshall Clarke developed a close relationship with Letsie I and later with his son Lerotholi, his intention being to strengthen the paramountcy and to bring effective British influence to bear on it. In 1886 the resident commissioner wrote to Letsie I proposing the establishment of a Basotho national council which would replace the pitso system. This proposal was accepted by Paramount Chief Letsie I in 1889. (The establishment of the national council was, however, to be delayed until 1903 because of the opposition of a number of influential chiefs.).

Letsie I’s reign lacked the firm resolve that had been shown by his father Moshoeshoe. During his reign the nation was rent with rivalries among the contending chiefs, each vying for the paramountcy.

MOKUBUNG NKOMO