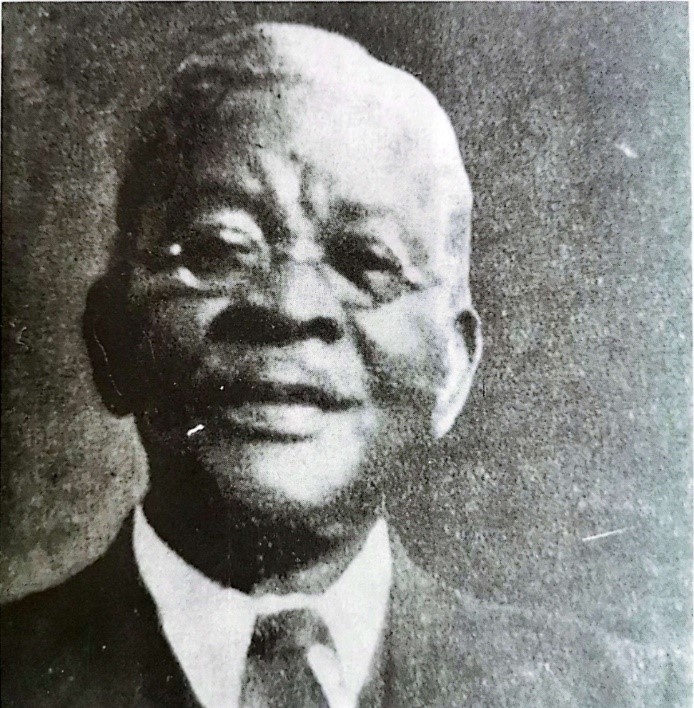

RUBUSANA, WALTER BENSON

- 4 Min Read

Walter Rubusana (February 21, 1858-April 19, 1936) was one of the most prominent Africans of his day, gaining distinction in the fields of religion, literature, and politics. Throughout his career, he championed the cause of racial equality and argued for the extension of the rights of Cape Africans to Africans in the rest of South Africa.

He was born in Mnandi in the Somerset East district of the Cape, the son of a senior counselor to paramount chief Sandile kaNgqika. His father sent him to a mission school at the age of six, then to Lovedale in 1876 where he studied until 1882.

PHOTO CAPTION: Walter Rubusana. SOURCE: EA Library

In 1884, he was ordained in the Congregational church and became a minister at the East Bank location in East London, where he was to remain for the rest of his life. Educational and religious facilities for Africans flourished under his direction, and he eventually became vice chairman of the Congregational Union of South Africa. His political views were strongly grounded in his belief that racialism was unChristian.

In l898, he was a prime mover in the establishment of the Xhosa newspaper Ilizwi Labantu (the Voice of the People), which promoted the views of Cape Africans who found John Tengo Jabavu’s Imvo Zabantsundu too cautious. Rubusana acted as an advisor to Dalindyebo, paramount chief of the Tembus, and, in 1904, accompanied him to Britain for the coronation of Edward VII.

Rubusana remained in London into 1905 to oversee the publication of the revised Xhosa Bible, in the translation of which he had played a major part. He was also the author of several Xhosa hymns, and of Zemk’ Inkoma Magwalandini (Defend Your Heritage, 1906), which is an anthology of traditional epic poetry and essays on religion, and is regarded as a Xhosa classic. He is also said to have received an honorary doctorate from McKinley University, a correspondence institution in the United States, for his work, A History of South Africa from the Natwe Standpoint (1906).

When the short-lived South African Native Convention met at Bloemfontein in 1909, Rubusana was elected its president and, later that year, accompanied its deputation to Britain to petition against the colour bar clauses in the South Africa Act. In 1911, he attended the Universal Races Congress in London, where he met W.E.B. DuBois and other early pan-Africanists.

Putting the liberal policies of the Cape Province to the test in 1910, Rubusana, with the backing of the Progressive party, ran for the Cape Provincial Council and was elected for the constituency of Tembuland, thus becoming the only African ever to sit on a provincial council in South Africa. From this position, he played a leading role in the unsuccessful efforts of Africans to stop passage of the 1913 Natives’ Land Act.

As head of the Cape-based South African Native Congress, Rubusana was among the founding members of the South African Native National Congress (later the African National Congress) in 1912, and was elected one of its original four vice presidents.

In 1914, he went to Britain with the SANNC delegation which protested the Land Act, believing like most politically progressive Africans at the time that the black man’s best hope lay in imperial intervention.

Rubusana’s membership in the Cape Provincial Council was opposed by Jabavu and the South African Party, and, in the election of 1914, Jabavu was persuaded to stand against Rubusana to divide the African vote and thus assure the return of a white candidate. Rubusana received 852 votes to Jabavu’s 294, a disgrace for Jabavu which underscored his final eclipse arnong Cape African leaders. For the duration of World War I, Rubusana and other SANNC leaders suspended all protest activities in the futile hope that African loyalty would be rewarded with concessions after the war.

In 1919, Rubusana, now in his 60s, joined younger leaders in drafting the SANNC constitution. Thereafter he retired from active politics, and in 1936, died in East London at the age of 78.

GAIL M. GERHART